Down Again

While in many parts of Europe (like Austria, Germany, Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Croatia), the Christkind (Christ child) brings presents on December 24; Santa Clause is in charge in the United States, giving gifts to the children.

According to the legend, Santa Clause is living at the north pole, where he gets letters from children worldwide who tell him what they want for Christmas. Then, on December 24, he is on tour in his sleigh, pulled by reindeer to deliver the presents.

While the children are asleep in the night from December 24 to 25, he lands his sleigh on the roofs of their houses, enters it through the chimney, and leaves the presents there. Usually, the children also place a glass of milk and cookies there for Santa.

This idea relates to a poem called The Night Before Christmas, from 1823. The author also mentions reindeer in the poem, although the well-known Rudolph was not part of it until he was added in 1939.

The roots of Santa seem to be found in Turkey, where Nikolaus, the bishop of Myra, lived. Several legends surround his life, and he was already celebrated back in the Middle Ages on December 6, which is still celebrated in many parts of Europe.

However, the Santa we know today, the man with a bushy white beard and red clothes, is 100 % a creation that developed during the 19th Century. Especially the yearly promotion by Coca-Cola, where the cartoonist Haddon Sundblom drew a portrait of Santa each year between 1931 and 1964, influenced the image of Santa Claus.

I write about this because Santa Claus also plays a role in financial markets, as a specific calendar effect happens around Christmas. According to Wikipedia

A Santa Claus Rally is a calendar effect that involves a rise in stock prices during the last 5 trading days in December and the first 2 trading days in the following January. According to the 2019 Stock Trader's Almanac, the stock market has risen 1.3 % on average during the 7 trading days in question since both 1950 and 1969. Over the 7 trading days in question, stock prices have historically risen 76 % of the time, which is far more than the average performance over a 7-day period.

So, does Santa deliver another Christmas present for investors this year?

There was at least a glimpse of hope after the US CPI number for November came out on Tuesday. Again, inflation year-over-year rose weaker (7.1 %) than expected (7.3 %), or 0.1 % instead of the expected 0.3 % month-over-month. Producer prices are also falling, and it is safe to say that the first inflation is over.

Markets took the numbers benevolently; the S&P 500 opened about 100 points higher. While 7.05 % inflation was bad in December of 2021, the market now considers it bullish, obviously because inflation is consistently falling since the summer and has fallen more than expected in the last two months, October and November. However, the FOMC decision on Wednesday changed the situation, and the gains evaporated again. At the press conference, Jerome Powell stated that it is still a long way, and he denied that the Fed considers cutting rates next year. But obviously, US treasury markets did not buy it. 2-year and 10-year yields remained pretty much at the levels after the CPI was published, while the yield curve flattened (got less inverted) a bit.

However, as I wrote in Sonne, do not pay too much attention to markets’ expectations regarding future interest rate developments. Currently, the dominant narrative (at least in my perception) is that inflation will slow significantly in the coming months.

Yet, that does not change much for my outlook on stocks over the medium term because if inflation is going down swiftly, the reason would be a severe recession, which would be bearish for stocks.

So, what are the arguments for fast disinflation in the first quarter of 2023? Firstly, proponents of that thesis (rightfully) point out that monetary policy works with a lag (studies say about 12 to 14 months), and therfore, according to the disinflationists, inflation needs to fall anyway. It is hard to speak against that; the current trend clearly underlines that consumer prices are past their first peak. The question is whether it will fall back to the Fed’s intended goal of 2 %.

Consumer goods price inflation has been falling like a stone recently. Given the shift in consumption patterns since the pandemic (from services to goods), they are also heavier weighted in CPI. Yet, I assume service inflation will stay sticky or rise further in the coming months.

Rent prices were the most robust rising component in the CPI (+0.8 %), but they are a lagging indicator. On a 3-month annualized basis, inflation excluding rent is already slightly deflationary. Additionally, prices for used cars are deflating significantly (-2.9 %) at their fastest pace for years. Other downside surprises in November were medical services (-0.5 %), airfares (-3 %), and hotels (-0.7 %).

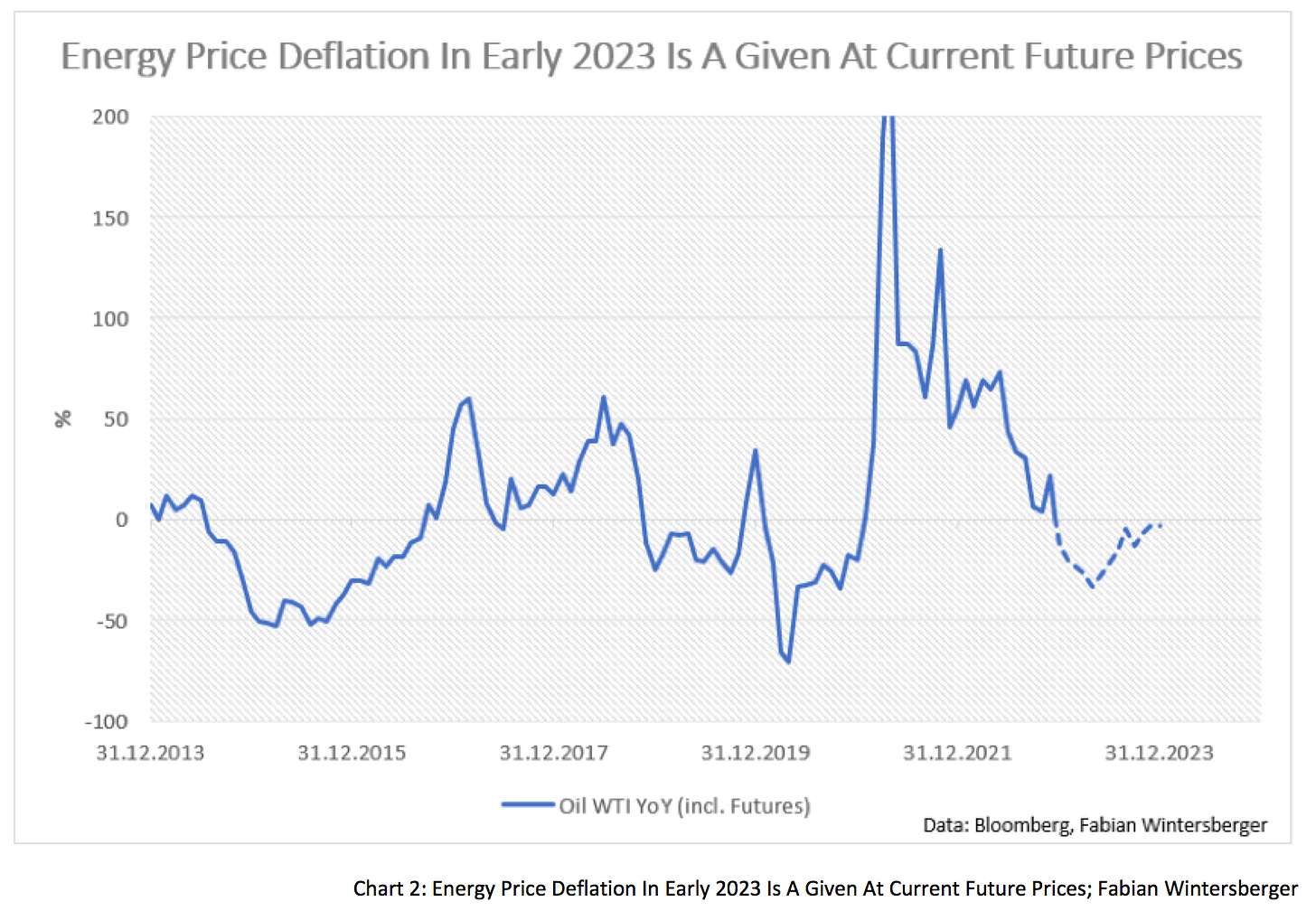

Additionally, falling natural gas prices and futures prices for oil indicate that energy inflation, one of the main drivers of price increases this year, might become deflationary in the coming months. A crucial factor here is weak energy demand from China because of its zero-covid policy, which is still in place.

Thus, it is probably pretty safe that inflation will continue to fall in the coming months. But what about the Fed’s goal of a soft landing? Some economists argue for that, for example, former Fed economist Claudia Sahm.

Besides the fact that the rate hikes will unfold their full effect in 2023 and pull inflation down, Sahm argues that the labor market remains relatively robust, which, according to her, is an indicator that a soft landing is still in the cards.

The most important thing for consumption is income, and the continuously solid nominal wage growth in the US shows that workers still have the upper hand (according to Sahm). If inflation is coming down, but nominal wages continue to rise, the result would be rising real wages.

Here, one may argue that this sows the seeds for a wage-price spiral, which fuels inflation. Nonetheless, the link between inflation and wage growth is by far not as straightforward as some economists claim, as a recent IMF working paper shows.

Additionally, the Fed is already slowing the pace of rate hikes. Currently, market participants expect three more rate hikes in 2023, 25bps each. Sahm argues that this is crucial to achieving a soft landing, and further, she points to a recent speech by Fed vice chair Lael Brainard, who claims that the 2022 inflation has been mainly due to the supply shocks induced by covid and Putin.

Even a recession can be avoided, something most economists forecast with almost 100 % certainty, Sahm claims. Interestingly, her argument is based on income inequality in the United States. She argues that since 2000, the US economy only went into recession when top incomes took a hit because they are responsible for most of the consumption expenditures. Further, she claims that even low-income earners are financially healthy, even though current inflation impairs that a bit.

At first sight, all those arguments look convincing, I have to admit. But still, even though I agree that inflation rates will come down in the coming months, I am not convinced that the Federal Reserve will succeed in bringing inflation back to 2 % or achieving a soft landing.

Firstly, I would argue that there are different reasons why consumer prices fall. Either they fall because production is increasing or because interest-rate increases decrease demand. If production increases, supply reacts to solid demand, and production levels are extended.

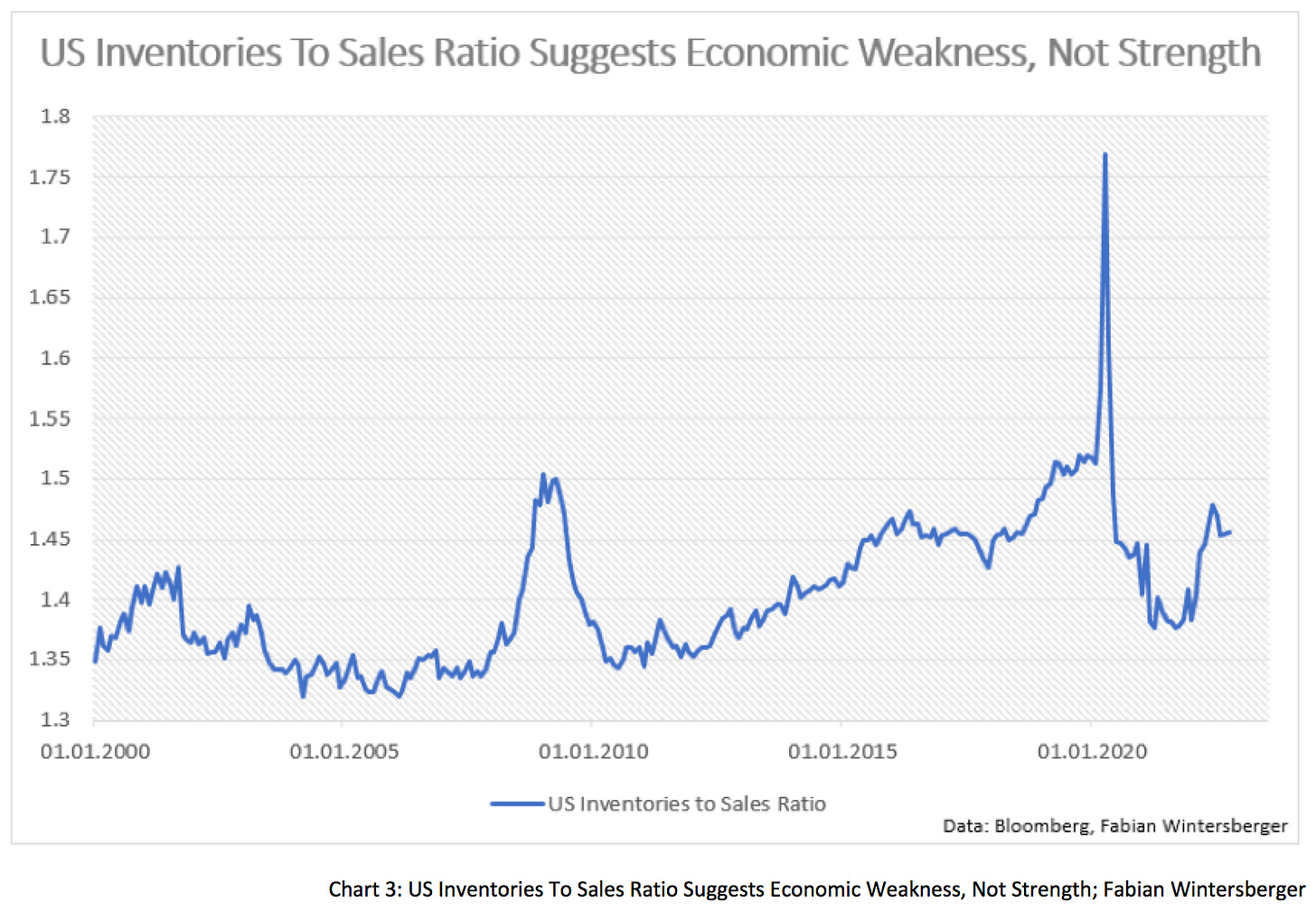

However, suppose consumer prices fall because producers observe that they cannot pass cost increases easily to consumers. In that case, economic activity goes down, and prices fall because inventories are driven down. If that is true, then inflation is going down for the wrong reasons, and lower price increases result in narrower profit margins.

The US inventory-to-sales ratio is about as high as in 2019, before the pandemic when the economy was already cooling. The big spike is due to covid and sharply declining sales during the lockdown period, while the latest increase is because high prices are already a burden for consumers. On the other hand, warehouses are full because businesses piled up stock to become less dependent on fragile supply chains.

Therefore, I would argue that the drop in inflation is due to the fall in real wages, not because of economic strength. Admittedly, the labor market remains robust, but labor is a lagging indicator and hence not a sign of a strong US economy, in my opinion.

Another gauge is the number of so-called zombies, who might be in trouble if interest rates remain elevated, though probably not immediately because many did refinance through longer-duration bonds. Currently, nearly every fourth business in the Russel 3,000 is a zombie. While rates were low, they could easily refinance their debt, but now their indebtedness could become a problem.

Additionally, the recent fall in oil prices is partially due to the weak demand from China and the depletion of the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. The pricing in future markets is connected with current market expectations; therefore, prices could easily adjust if China reopens, for example, and the demand for energy rises again. Therefore I expect that energy price inflation might not be as severe as current future prices may indicate because supply cannot increase because of spare capacity in such a scenario.

As I wrote last week, the US labor market is much weaker than the numbers on the surface would suggest. Furthermore, it seems that current layoffs are over-proportionally affecting white-collar workers. That is very unusual because typically, when a recession hits, companies start to lay off low-income blue-collar workers before white collars follow when the recession deepens. That also contradicts the hope for a soft landing because most white-collar workers are part of the middle class, and hence it seems that they are more affected by the current economic slowdown.

Also, a fall in consumer goods inflation was expectable for those familiar with the Cantillon Effect. Those who are, know that price inflation spreads from the increase of the money supply over those areas of the economy where the money spreads and elevates demand.

Starting from an increase in money supply, the result was increasing demand for consumer goods because consumer prices for services fell because of the lack of supply and, respectively, the fall in demand because of covid-fears. Construction activity rose, and, as a result, prices for lumber, cement, or other commodities spiked. With the end of the covid policies in the US, the demand for services has risen again, and the market is now looking for a new equilibrium level in the post-covid world. Further, the gap in labor supply, which resulted from the shift in job seeking during covid, is pushing up wages in the service sector.

I do not expect demand for consumer goods to fall back to pre-covid levels; hence, I assume that inflation will stay elevated. The gap in the labor supply will keep wages (therefore prices) elevated, and as a result, I would not agree that proponents of a rapid decline in inflation are correct.

Without a doubt, the inflation peak in the US is in, at least for now. The contraction of the money supply because of interest rate increases and QE also plays a significant role there. Although, a fall or a slowing growth in inflation was already evident due to the base effect.

Falling US energy prices also played a significant role in why consumer price growth remained subdued in November. The tense situation in the energy markets will continue, and OPEC+ will probably start to cut production soon, maybe somewhere in the next few months. And, at some point, the SPR will not help anymore.

Therefore, I would argue that investors should remain in defense positioning into 2023. While I write these lines, Christine Lagarde is speaking and announcing a more aggressive ECB, despite it only hiked rates by 50bps at the current meeting. According to her, the ECB will act more restrictive than markets presently anticipate. As a result, I would argue that after Powell and now Lagarde, Santa Claus will not be generous to investors this year, and a Santa rally has become less likely.

If one assumes that a drop in inflation in the coming months will be a buy signal for equities, I urge you to think again. For the bond market, I would say that one should wait for next year to enter long positions. Time will tell if I am right about that.

How many times can it change, how long will I be restrained,

It’s all appalling to think that, all my time seems to be wasted

Will it stop or is it only beginningChimaira - Down Again

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! You can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox if you like what I write. Also, it would be fantastic if you shared it on social media or liked the post!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice)