Sonne

Since the beginning of humankind, the sun has been a helpful guide for orientation. In times when navigation systems had not been invented, the sun was one of the reasons why wayfarers, traders, or seafarers did not lose their way and reached their intended goal. Indigenous people used the sun as a guide through the savanna because it never lied and showed if one moved in the right direction.

However, the sun is not only crucial for orientational reasons. It is also the main reason for the existence of life. If there is no sun, there is no light, and without light, there is no life. If it did not rise in the east every morning and send light and warmth to the earth, it would mean everlasting darkness, hence death.

Because of that alone, there is something mythical about the sun, and therefore it is not surprising that the sun was also essential for ancient religions. In all of them, the sun god, no matter if called Ra, Helios, or Sòl, is one of the most important gods.

Interestingly, we also find parallels between the sun and the Christian god. So as God, the sun is the creator of life. It may be farfetched, but maybe it is not a coincidence that the designation of Jesus, the personification of God on earth, as God’s Son sounds similar to God’s Sun.

Fascinatingly, the personification of the sun is not an invention of Christianity, and there are many similarities between Jesus and ancient sun gods. There are claims that the history of the Egypt sun god Horus is as follows: He was born on December 25th, which was prophesied by a star in the east, whom three kings followed. Horus was a teacher at the age of twelve, was baptized at the age of 30 and began his ministry, traveling around with disciples to perform miracles. He was also called God’s sent Son or the Lamb of God. He died crucified because of betrayal and was resurrected after three days.

If one takes those claims for truth, one will find many similarities with the history of Jesus. While I am not a theologist and do not claim to be, I think that it might be that the catholic church may have taken ancient stories and put them into its religious corset.

However, one can conclude that the birth of Jesus, December 25th, has to do something with the sun. On that day, the sun is finally rising higher again after being under the cross of the south for three days. Therefore, the sun can be understood as a guide to move in the right direction and as a spiritual signpost.

Within our global financial system, there is also a sun that investors use to find the way and thus can be understood as the center of the financial universe. Something that guides the actions of actors in the market and influences them solely by its existence. That sun will be my topic for today: the yield curve.

Yields and the yield curve play a significant role in commentaries, analysis, and prognoses. It goes so far that some mystify the yield curve as something with divine predictive power, similar to an oracle. Sentences like Yield Curve Almost Flashes Recession, What The Yield Curve Is Telling Us, Bond market signals concern Fed’s bid to cool inflation will backfire, or Flattening Yield Curve Is Sending Message About The Fed’s Rate Plans have been all over the financial media for years.

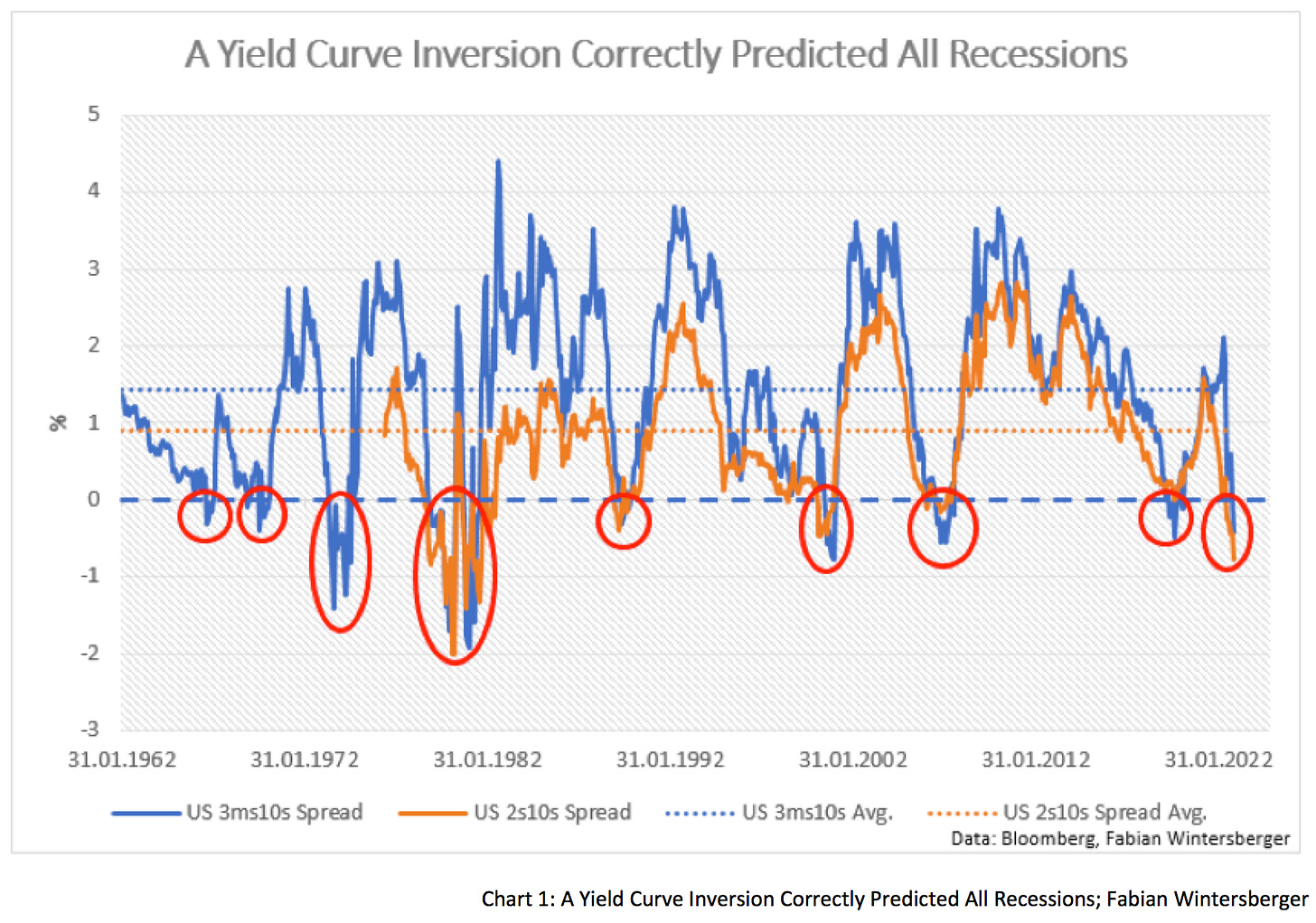

In times when longer-term yields are below short-term yields, when the yield curve inverts, it is a reliable indicator of coming market turbulence. Since 1960, an inverted yield curve correctly forecasted all economic recessions in the United States; therefore, many observers see it as a guideline for future economic development down the road.

So far, it is understandable that the rates and bond markets are surrounded by something I would describe as a mystic aura. Remarks about the yield curve make people sound extraordinarily smart at first because the rates market is not as easy to understand for retail investors who primarily invest in equities. After all, investing in most bond markets is usually up to big, institutional investors.

Many forecasts about future economic development rely on the yield curve, which shows the investment yield of an asset for different durations. The shape of the curve leads to conclusions about the expectations of market participants about the actual and future development of the economy. Usually, the yield curve is slightly upward-sloping because one can assume that investors only invest capital in longer-term assets if they can expect a higher yield for their long commitment.

In a free market, where interest rates are the result of supply and demand, one can assume that the yield curve's slope is relatively flat because it otherwise would lead to arbitrage opportunities and, thus, to a flatter curve afterward. Yet, it still would slope upwards in a continuously and sustainably growing economy. For example, if a rise in productivity growth would lead to lower inflation expectations down the road, longer-term yields would fall faster than short-term rates (bull flattener).

Nevertheless, one knows that rates are not solely a result of supply and demand, especially short-term rates, which also guide longer-term rates because central banks set them. For that reason, central bank decisions influence interest rates and the yield curve's slope.

If central banks are slashing interest rates, short-term rates crater. However, long-term yields are not affected similarly because, according to the Theory of Irving Fisher, they are also influenced by growth and inflation expectations. As a result, long-term yields also fall, but not as much as short-term yields because additional liquidity for markets also means that one can expect a rise in prices in the future (bull steepener).

Lower prime rates lead to an (artificial) economic boom and cause long-term inflation expectations to rise, hence long-term yields. Here, I want to add that long-term interest rates are also influenced by statements from central bankers about future inflation developments (e.g., transitory) because they affect expectations.

However, if inflation numbers show a rise in the price level, longer-term rates start to cribble upwards (bear steepener). That indicates that the additional liquidity central banks poured into the markets have caused economic imbalances, or as Keynesian economists say, the economy overheated.

At one point, central banks have to counteract and have to start to raise interest rates. As a result, it takes liquidity out of the market (because it tightens financial conditions), which leads to dampened growth and inflation expectations. Hence, long-term interest rates do not rise as much as short-term interest rates because short-term rates are more directly influenced by the prime rate (bear flattener).

If the central bank slams the breaks and raises interest rates, it will likely overshoot because of insufficient information. Within this step, one can expect that short-term interest rates, at some point, are higher than long-term interest rates, and the curve inverts. Liquidity contractions lead to falling growth and inflation expectations, a potential sign of recession.

It is essential to understand that this does not happen because market participants expect a recession but because central banks raise short-term interest rates too much. If market participants were expecting a recession, long-term yields would fall faster than short-term rates.

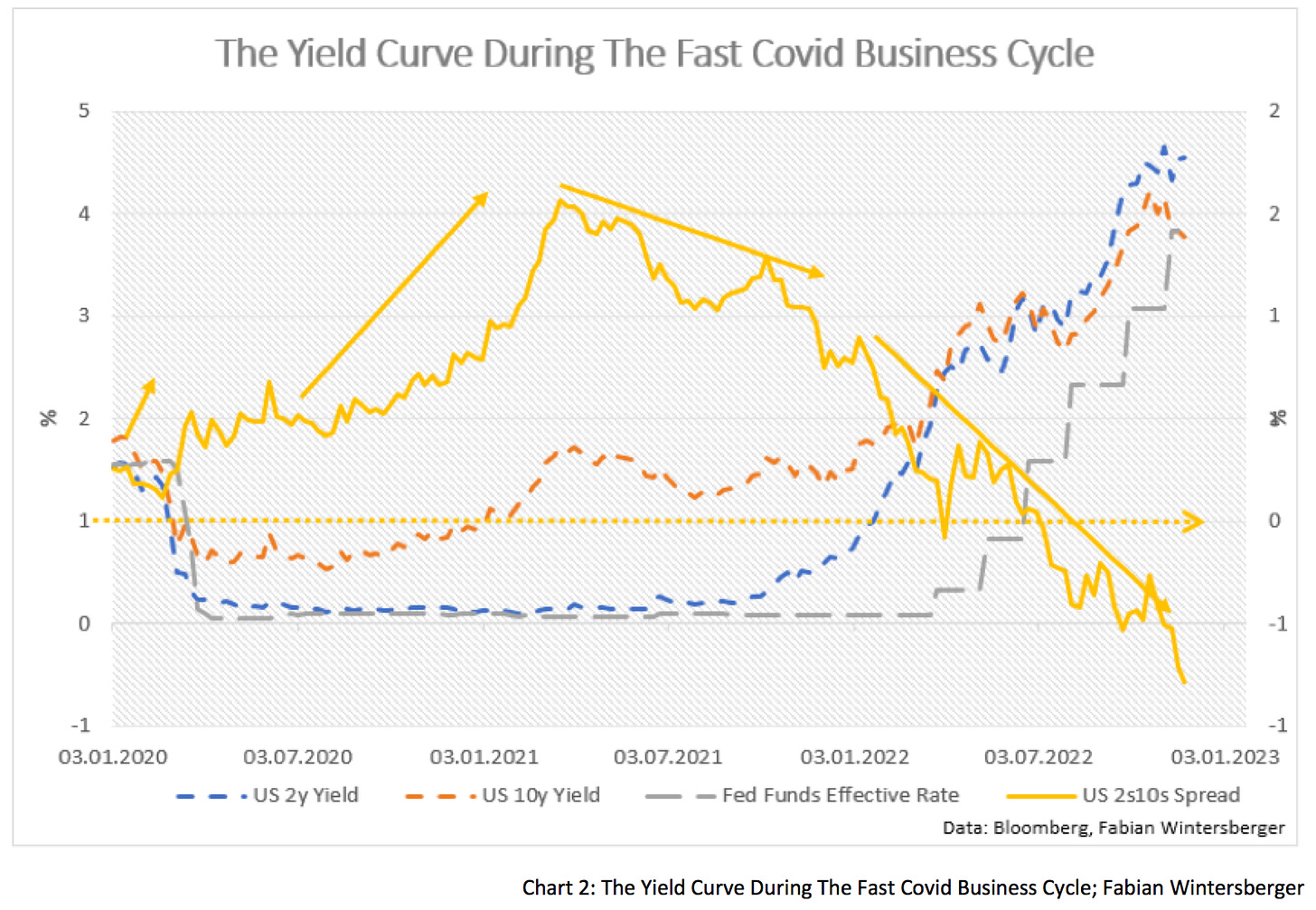

An observation of the development of the yield curve since 2020 shows the described changes in the yield curve’s slope beautifully. In March 2020, the Fed slashed interest rates, and interest rates around the curve cratered. Excess liquidity flowed into markets, fueling inflation (and growth) and causing a rise in long-term interest rates.

As inflation continued to rise, leading to Powell burying the term transitory, short-term rates started to shoot up in anticipation of a normalization of monetary policy and a fall in growth and inflation expectations. The liquidity tsunami of 2020 literally led to a business cycle on steroids.

Yet, as we know, there is another tool of central banks that shapes interest rates besides the prime rate: Quantitative Easing (QE). The idea is that central banks can lower long-term interest rates when they buy government bonds, which stimulates economic growth and raises long-term growth and inflation expectations.

If one investigates QE in the US, one discovers that the exact opposite of what the Fed intended happened in reality. Only during QE 1, when the Fed started to buy bonds on the secondary market long-term interest rates did continue to fall. In 2014, interest rates began to fall when the Fed bought fewer bonds (tapering). Undoubtedly, one can conclude that Quantitative Easing was a total failure because it neither did create growth nor inflation, and interest rates started to rise initially when the bond-buying started.

At first sight, this is illogical because QE should lead to a rise in demand for bonds, considering everything else stays equal. Nonetheless, that is the crux of it because, in reality, not only does the demand side change because of Fed buying, but QE also influences the supply of bonds on the market.

One factor is, as noted above, the change in supply, whether in the primary or secondary market. If one assumes the US Treasury starts to issue more bonds and demand for them is not growing by the same amount, interest rates begin to rise. On the other hand, QE could lead investors to buy bonds at auction and sell them shortly afterward on the secondary market. If supply (the number of bonds offered for selling) rises faster than the amount of demand, the Fed creates, then interest rates rise as well.

Apart from that, the liquidity injections of QE have another effect that could be overlooked. An artificially created, low-interest rate environment, paired with the Fed Put, causes investors to take more risks. They may sell safe-haven assets (bonds) and use the revenues to buy higher-yielding or riskier assets. Investors possibly sell bonds to buy equities. This lowers bond prices/raise yields while demand for stocks rises, fueling a price bubble in equities.

QE drives investors farther out on their individual risk curves. Instead of US treasuries, they start to buy higher-yielding BBB bonds or stocks. If one looks at bond spreads (risk premiums compared to safer US treasuries), one could come to this conclusion. During QE, risk spreads narrowed, which could be traced back to a raise in demand for those higher-yielding bonds.

Nevertheless, it is crucial that the yield curve is not a crystal ball of market participants apart from what some people often assume. Interest rates solely reflect the expectations of market participants about future economic developments. May it be expected increases in the prime rate, which influence short-term interest rates, or growth and inflation expectations on the long end.

A perfect example is future real yields. While current real yields are calculated by subtracting consumer price inflation from the effective prime rate, it is more difficult for interest-rate products with longer duration. One cannot simply deduct inflation from nominal yields. The correct way to calculate real yields is to subtract breakeven interest rates, which gives the interest rate for inflation-linked bonds (e.g., TIPS).

Breakeven rates tell us the average inflation rate market participants expect over a specific duration. Although one can assume that, on average, the sum of all market participants mostly has a better assessment of future inflation rates than one market participant, that does not know that the market is always right.

The idea goes back to an experiment by the scientist Francis Galton, who let participants of a competition estimate the weight of a cow. When he analyzed the estimations, he observed that the median estimate was pretty close to the cow’s actual weight, while the calculated average even gave the actual weight.

In the last decade, the average expected inflation rate for the coming ten years (10y Breakeven rate) was around 2 %. Last year, it shortly rose to 3 %, but because of the latest disinflation, expectations returned to 2 %. It is up to every investor to assess if market expectations are correct.

Actually, one could argue that it is much harder to predict average inflation over ten years than a decade ago. On the one hand, inflation is still at its highest since the 1980s, and the Fed’s plan to shrink its balance sheet is unlike any time in history. That means that current assessments are surrounded by great uncertainty.

Recently, the Fed has reduced its holdings by 1.5 % by letting bonds mature on its balance sheet. If they want to reduce the balance sheet back to the level of 2020, it needs to reduce it by 41 %.

That means that if it stays on course, the Fed needs to recycle bonds into the markets on an unprecedented scale, which could easily lead to lower bond prices/higher yields. In that scenario, I would not bet on a continuing fall in interest rates.

The last time the Fed tried QT, one could observe the opposite effect of QE. Shrinking liquidity leads to a fall in prices of risk assets (lower demand) and causes reflux of capital to safe-haven assets, like treasuries. One must ask if the market can absorb the rising supply in case of such an extreme Fed balance sheet reduction.

Currently, the fall in inflation led to looser financial conditions within markets. The yield curve indicates that market participants expect that central banks will get inflation back under control (for whatever reason). Somehow it seems that markets might even believe in a soft-landing scenario (at least, the current assessment of participants in the rates market expells that, in my opinion).

Time will tell if the current expectations are correct. Nonetheless, a premature declaration of a win against inflation might lead to a readjustment, and additionally, markets do not pay enough attention to the renewed fiscal stimulations of governments.

If central banks change course prematurely and flood the system again with liquidity through QE, this could influence inflation expectations considerably. Investors should remember that when they are planning future investment decisions if they believe that we have already seen the top in long-term interest rates.

If history is any guide, the stock market has yet to face its most significant problems in such a scenario. Although market participants evaluate it that way, keeping interest rates around 5 % will not be a Fed pivot. That is just another proof of the extreme bullish bias that has developed among stock market investors over the last 20 years.

Just as the sun is a helpful tool for reaching the destination, or as god is a spiritual signpost, the yield curve can be a useful tool for future trading decisions, but thou shalt not take the message of the yield curve for granted. Therefore, a transfiguration of interest rate markets of being an almighty crystal ball, as some analysts do, is incorrect. As John Maynard Keynes once correctly noted,

Markets can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent

That is an excellent analogy, I think.

Investors should definitely deal with the implications of the yield curve and its meanings because this helps get a more differentiated look on markets, apart from the usual credo that stocks only go up. But also, the yield curve can be wrong, just as last year when it forecasted that there would not be a single rate hike before 2024. However, like the sun, the yield curve will always be a guide for investors. Or, as the German band Rammstein is singing:

One - here comes the sun

Two - here comes the sun

Three - she is the brightest stars of all

Four - from heaven she won’t fall

- Rammstein - Sonne -

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! You can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox if you like what I write. Also, it would be fantastic if you shared it on social media or liked the post!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice)