Although low inflation is generally good, inflation that is too low can pose risks to the economy – especially when the economy is struggling. - Ben Bernanke

We are all for quantitative easing in Europe, but it is not enough. Deflation and secular stagnation are the risks of our time. - Lawrence H. Summers

Those were the days! From 2008 and 2021, concerns of deflation, a fall in the general price level, have dominated the economic discourse. Ben Bernanke led the Fed on the unknown path of quantitative easing, but inflation did not want to pick up as Fed economists expected.

Shortly after that, the European Central Bank followed the Fed on its path, and Europe suffered from the same fate as the US as neither inflation nor the economy got restarted. QE failed miserably, just like it did in Japan and the United States. However, what should be memorized from those days is that the only thing QE did achieve was supporting higher government spending and fueling asset price bubbles. What it did not succeed was a return to higher economic growth.

On the contrary, continuously low consumer price inflation led to a feeling of false security from central bank policymakers and politicians. Lawrence H. Summers and others formulated thesis after thesis to explain why the continuous decline in interest rates was caused by something other than central bank interventionism.

Undoubtedly, carelessness should become one of the primary reasons inflation unexpectedly returned. When governments followed the Chinese example, shut down vast parts of the economy by decree, and pumped unprecedented amounts of money into the real economy, hardly anyone thought that artificially high demand and falling supply might do what QE did not achieve: creating inflation.

It took 13 years until forever low inflation became a relic of the past. Since 2021, one feels repeatedly reminded of the following quote from American humorist Sam Ewing:

Inflation is when you pay fifteen dollars for the ten-dollar haircut you used to get for five dollars when you had hair.

But first, let us see what the market has done since last Friday. American and Japanese stock indices, gold (in dollar terms), 10y Bunds, and 10y Treasuries are slightly up, while commodities (Bloomberg Commodity Index) and Chinese and European stock indices are somewhat lower.

Europe is suffering from weak demand from China, where the re-opening did not cause the expansion many had hoped for. Yet, that might change soon, as an unexpected industrial activity pick-up suggests.

The drop in yields took me by surprise, but I am still not convinced that the time for longs in bonds has come, and I think we will see higher yields again in the coming weeks.

Lower-than-expected CPIs & PPIs in Europe have nourished hopes that the rate-hiking cycle of the ECB will end soon. While data was released that Spanish consumer prices rose only 2.9 % in May, while the consensus expected 3.3 %, and European bond yields dropped. On Wednesday, lower-than-expected inflation rates in France and Germany also drove bond yields lower.

Yet, the recent drop in consumer price inflation should be taken with a grain of salt. After all, they merely reflect the degree of how much governments in those countries intervened in markets. Simultaneously, eurozone countries that handed out extensive stimulus checks to the people have artificially elevated consumer prices.

While the recent drop in German consumer prices can be traced back to the introduction of the 49 euro ticket for public transport and the gasoline discount, the Spanish government intervened extraordinarily heavily in markets. Looking at the fate of the price controls back during the Nixon presidency in the 1970s should hint at what will happen when those price caps are lifted.

Simultaneously, the ECB urges governments to scale back on public spending support schemes as inflation rates drop. The problem is that once government spending increases, spending does never stop and even gets increased. Now, the Italian government under Giorgia Meloni wants to spend another billion to stimulate growth. A classical socialist economic policy that has failed for decades.

In Austria, inflation will likely stay elevated for longer as most worker unions achieved favorable wage settlements that will narrow profit margins. That contributes to a likely pick up in unemployment later that year.

Apart from that, energy-intensive industries in Europe look for places to relocate production since a previously important factor of production, cheap energy (from Russia), has also become a relic of the past. Stubbornly, Europe is unwilling to use its natural gas sources for environmental reasons.

Like the United States back then, Europe was a net energy importer. The end of the gold standard to finance a war (Vietnam) and a not restrictive enough central bank had weakened the currency and drove inflation up. Similar things are currently happening in Europe but accompanied by heavy regulations that dampen economic activity anyway.

Currently, the euro profited from the anticipation of market participants that the ECB will stay more restrictive for longer than the Fed. Nevertheless, this assumption will be a fallacy, even though a statement by Fed vice governor Jefferson (Philadelphia Fed) has led to a shift in market expectations regarding a June rate hike, which has been priced out since he said that he favors a pause.

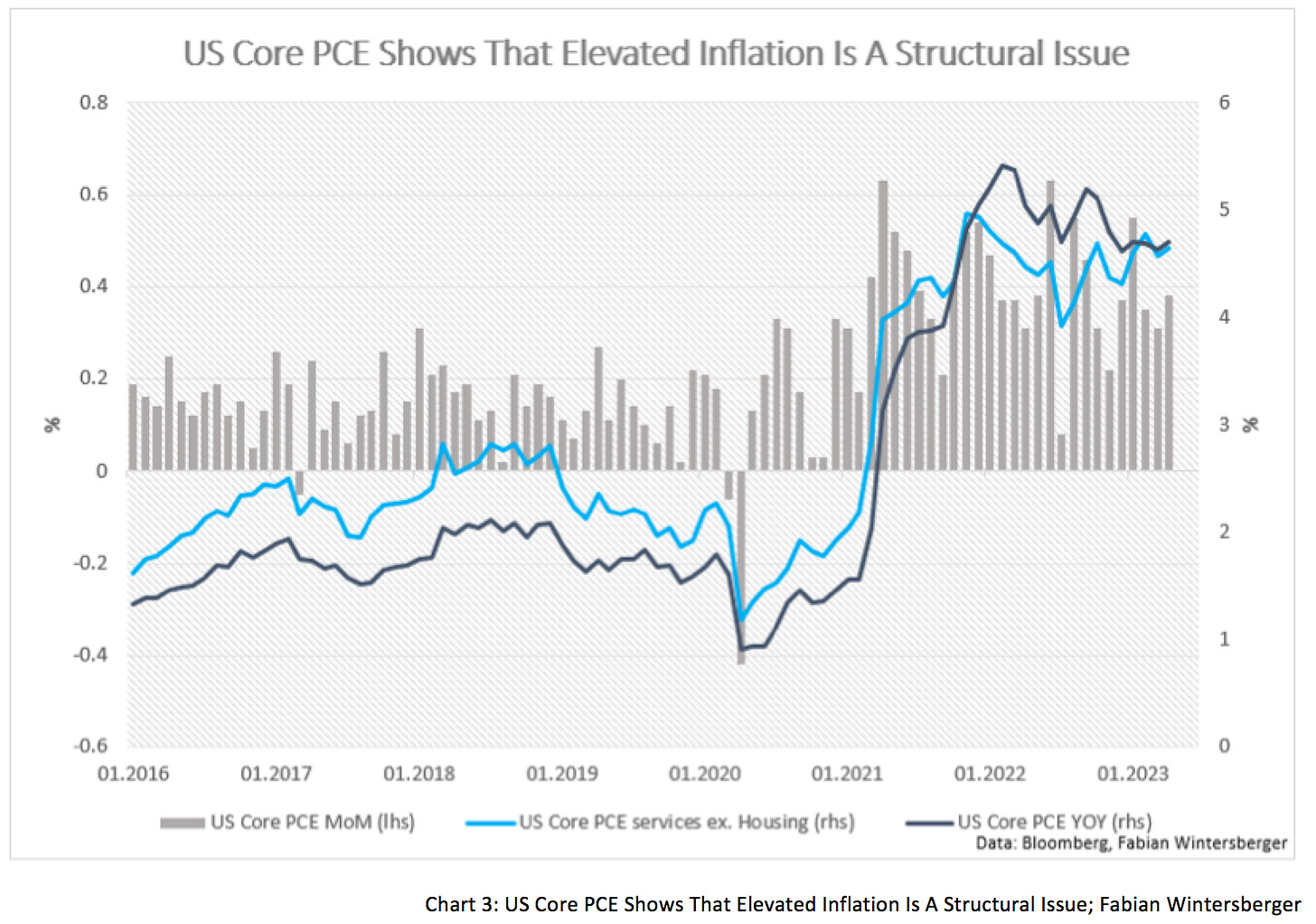

Last week’s PCE numbers underline the problem for the Fed. Consumer spending remains solid and sustainable higher month-over-month rates of change are a sign that inflation has become more structural. It might be dangerous if the Fed gives up on being restrictive too soon. I think that a pause at the June meeting is nothing but a done deal, despite the pivot from the Market after Jefferson’s remarks.

There is a massive debate about what caused the rise in inflation. While economists like Isabella Weber have the thesis that high inflation is a result of greedflation, meaning that businesses are hiking up prices higher than it is justifiable, a paper by Francesco Bianchi, Renato Faccini, and Leonardo Melosi concludes that the significant increase in government spending has been the main driver.

In the meantime, home prices show a more nuanced picture. On the one hand, house prices fell year-over-year in April, suggesting that US consumer price inflation will go down further in the coming months. Housing inflation is showing up with a lag in CPI and (assumingly) topped at 8 % in April.

The drop in (NSA) home prices year-over-year was the first since May 2012. Home prices (NSA) were down 1.6 % on a month-to-month basis. A look at the state level gives a more nuanced picture. According to Zillow, home prices drop in the West while mostly rising in the East.

The Zillow Index and the (seasonally adjusted) Case-Shiller Index show the same picture month-over-month. Prices for homes start to pick up again, and several earnings calls from landlords support this and hence do not support the thesis that housing inflation will drop as quickly as it appeared.

If rent- and home price inflation rises again in the coming months, we will undoubtedly see additional rate hikes from the Fed. I do not assess Jerome Powell’s character, such as he will pivot at any minor turbulence.

Market participants still expect that the Federal Reserve will be done with raising interest rates in July and that the Fed Funds Rate will decrease gradually from September to mid-2025 to 3 %. Thus, I conclude that most market participants are forecasting a soft landing.

Under that scenario, the labor market would likely cool a little, but there would not be a sharp increase in unemployment. As long as consumption is not going down fast, that might as well be the case. Yet, consumer sentiment indices give mixed signals about that.

While the Conference Board’s Consumer Sentiment Index suggests only a slight increase in unemployment to approximately 5 %, the Index from the University of Michigan shows a whole different picture. It suggests unemployment could rise to about 7-10 % in the coming six months. Historically, the divergence between both has always led to a rise in unemployment: at the end of the 80s, in the year 2000, and in 2008, where the increase in unemployment was the strongest, and it more than doubled.

Discussions about the debt limit drove down the US Treasury’s General Account at the Fed. When Democrats and Republicans finally finish a deal, Janet Yellen will push it back up. The additional supply of T-bills and Treasuries should drive yields back up.

Let us remember the findings of Bianchi et al.’s paper, where they find that a fiscal shock mainly drives a significant increase in inflation. When the TGA was driven down during the pandemic, the fiscal transfer payments strongly elevated consumer demand, and as a result, consumer prices sharply rose.

I do not expect the Fed to end its restrictive monetary policy until inflation is back at 2 %, even if it probably brings the economy into recession. The fear of repeating the mistakes of the 1970s under Arthur Burns is too high.

Additionally, it can be doubted that the US government is considering significant spending cuts. The US government has promised big subsidies for companies if they shift production to the United States. That means fiscal spending will remain high with a debt/GDP ratio of 125 %. If the Fed stays restrictive, interest rates expenses pick up at the same time the economy takes a full braking and tax receipts drop.

If the government wants to spend the same amount of dollars or even wants to spend more, it needs to issue more bonds at higher rates. Simultaneously, re-shoring leads to a backflow of off-shore dollars (cash or dollars from bond sales) to acquire land, labor, and capital goods.

Mid-term, it is implausible, in my opinion, that the economy will return to a deflationary environment like the one of pre-2020. Mid-term and long-term, I expect higher inflation, interest rates, commodity prices, and precious metal prices.

Short-term, I stick to my forecast from last week because I assume that the latest drop in yields will reverse once again. Sir John Templeton once said that the time of maximum pessimism is the best time to buy, and the time of maximum optimism is the best time to sell. Times, where everyone is buying bonds in anticipation of a pivot/recession, and a leveraged long-term Treasury bond ETF gets inflows of a billion dollars since year-end, do not sound like the bottom of a bear market.

The disinflationary impulse is likely to continue in Europe and the United States. However, everyone knows that the most challenging part of bringing inflation back to 2 % is getting it from 4 -2 %. Central bank efforts are continuously torpedoed by European governments or the US government, who continue to spend as if it was still 2015. But there will be no going back to the low-inflationary environment of the 2010s.

We soar above all mistakes on bruised, and battered wings ascend

To bring back the light again, passed imagination

Above all mistakes on bruised, and battered wings ascend,

To bring back the light again, passed imaginationRaunchy - Warriors

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! If you like my writing, you can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox. Also, sharing it on social media or liking the position would be fantastic!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice. I may change my view the next day if the facts change)

I agree regarding the entry point in LT bonds. When positive base effects for yoy Inflation end in June and inflation picks up higher again in July, it will again stop out a lot of Long Bonds investors imo. It's a tough market for the long bond guys. Their long term view on lower 10y yield is probably right, but the timing has been wrong for 18 months now.

The last 2% will clearly be the toughest!