Nothing But Mistakes

After my two-week vacation, I am finally back in the office. On Wednesday, I returned from Italy, where I spent one week with my family on the Adria coast and contributed to Italy’s economic growth. I enjoyed my last free day in Upper Austria yesterday and returned to the office today.

While one notices very little on the Adria coast that the world economy is coming down from its sugar high induced by trillions of euros and dollars that monetary and fiscal policy injected into the economy, my impression is that more and more market participants are finally noticing it.

However, several statements from central bank officials caught my attention in recent days and weeks concerning future monetary policy and inflation. I will get back to that after I want to address some of the latest published data that suggests that the recession that everyone fears is already here.

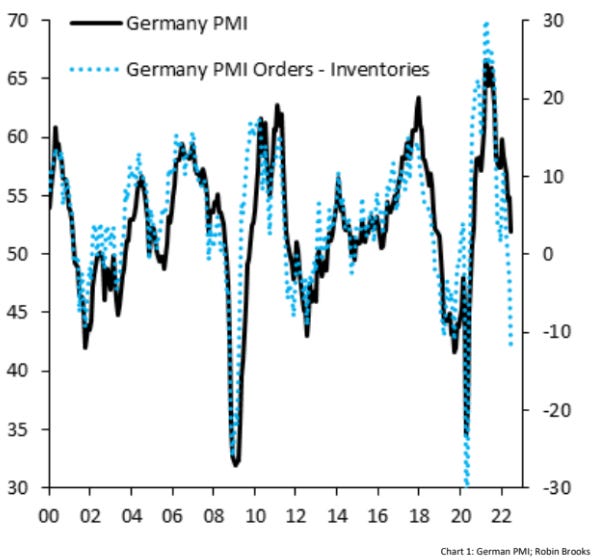

German PMI numbers from last week support the fact that we are already in a global recession. The inventory component of the PMI is already at levels not seen since the Great Financial Crisis. The fact that Germany is a vital contributor to global production displays the worsening economic situation.

In the first quarter, the economy in the Eurozone grew by 0.6 % compared to the previous quarter, while year-over-year growth was still at 5.4 %. However, the yearly number can be explained mainly since in Q1 of 2021, many parts of the European economy were still closed and influenced by governments’ lockdown policies. Further, the consequences of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the implemented sanctions will firstly show up in the GDP numbers for Q2. In June, the ECB revised growth projections for the Eurozone down by 0.9 percentage points compared to their March projection.

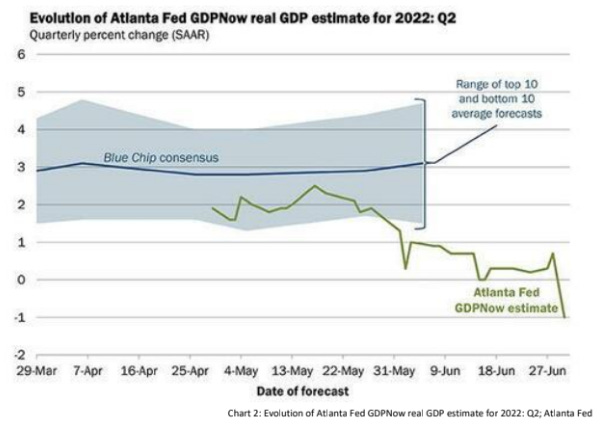

While the US did outperform the Eurozone economically in 2021, economic activity in the US is also struggling. GDP growth has been negative in Q1 (-1.6 % in a year-over-year comparison), and the Atlanta Fed’s GDP Nowcast for Q2 has also become negative recently.

Nevertheless, in contrast to the Eurozone numbers, the US growth numbers are strongly influenced by the Fed’s aggressive monetary tightening path. Despite the latest sell-off in the stock market and weak GDP numbers, the Fed is still assuring the market that it will follow through with its plans to hike interest rates by 50 - 75 basis points in the coming FOMC meetings. Lately, Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said that the Fed should err on the side of tightening too much.

At least in the United States, central bankers are trying to fight inflation. The situation in the Eurozone is very different, though. While the ECB phased out PEPP yesterday, it is already planning to start another QE program to prevent southern government bond spreads from rising too much.

The expectation that the ECB will do the unthinkable and now really normalizes monetary policy has widened government bond spreads. Especially Italian BTPs were hit hard after the ECB’s governing council meeting two weeks ago, which caused the ECB to call for an emergency meeting to discuss the situation.

A few days prior, on June 14th, Isabel Schnabel said in a speech at Sorbonne University that the ECB would not tolerate financial conditions that are not fundamentally justified and threaten the monetary transmission. That is a very interesting statement because she argues that the ECB will intervene whenever it is not satisfied with the free-market outcome.

Therefore I was not surprised that rumors came up that the ECB is already planning to start another QE program, although I am convinced that the ECB members will assure everyone that the new program is not QE. As a result, I do not expect the ECB to scale back on the central planning activities that it expanded since Mario Draghi’s term.

The European Central Bank will buy bonds from Italy, Spain, Portugal and Greece with some of the proceeds it receives from maturing German, French and Dutch debt in a bid to cap spreads between their borrowing costs, sources told Reuters.

The ECB plans to reinvest directly into government bonds from the PIGS-states. While the ECB probably will call this some rebalancing, some ECB critics might argue that this is covert government funding. Nevertheless, one can expect that a policy will not incentivize those governments to consolidate their budgets. It is particularly noticeable that, according to Reuters,

The central bank has divided the euro zone's 19 countries into three groups - donors, recipients and neutrals - based on the size and speed of a rise in their bond spreads in recent weeks, according to conversations with a half a dozen people at the ECB's annual forum in Sintra, Portugal. The spreads are gauged against German bonds, which serve as a de-facto benchmark for the single currency area.

By narrowing government bond spreads, the ECB is trying to keep the costs of refinancing for the pics as low as possible. Usually, the spread represents the additional credit risk that investors face compared to buying a bond from a debtor with less credit risk. If the spread between German Bunds and Italian BTPs is narrow, investors usually can assume that Italy will not have problems repaying its debt, for example. However, there is a catch because no one, who is not obligated to buy Italian government bonds, buys them anymore. The last buyer standing is the ECB, and this intervention will do nothing to change that.

Simultaneously, governments try to dampen the consequences of high inflation for the public via transfer payments, although I would argue that this will fuel the inflation fire. The same is true for price caps that are widely discussed these days, and those actions will not solve the problem of too little supply.

It seems that central bankers are still surprised that inflation rates are that high. Christine Lagarde said on a Panel in Sintra this week that the pandemic unleashed various forces, including the re-organization of supply chains, energy, etc. It is puzzling that apparently, nobody at the Fed or the ECB seems to believe that ZIRP and the expansion of the money supply combined with enormous fiscal spending played a role.

But it is easy to explain why QE in the 2010s did not lead to a pick up in consumer prices because the money was circulating in the financial economy. If the central bank buys a bond from a bank, the bond goes on the asset side of the central bank’s balance sheet, and bank reserves replace the bond on the asset side of the commercial bank’s balance sheet. Low-interest rates reduced the banks’ appetite to lend to the real economy because it was a risk not worth taking. Instead, their engagement in financial markets increased. Where the new money flowed, prices rose, for example, in the stock and real estate markets.

QE led to a crowding out of private investors until central banks became the primary buyer of government debt. Especially the ECB bought a load of bonds and is now approaching Japan’s levels in that they hold about the same percentage of total issuance.

Since the start of the pandemic, the implementation of credit guarantees, stimulus payments, and a loosening of monetary policy overstimulated demand and caused prices to rise. However, if one reads statements from central bankers, one could conclude that all this hardly played a role.

On the contrary, in Sintra, Powell announced that the Federal Reserve learned how little they understood inflation last year. Although I and many others warned that inflation would pick up the previous year, nobody at the central banks took notice. Instead, one mistake followed the other because it seems that no economist at the Fed or the ECB thought that, after years of failed attempts to push up inflation, money printing actually leads to price inflation.

My hunch is that, apart from the experiences of the last decade, this view is widespread because most macroeconomists at the central banks are Keynesians, and they primarily work with models where inflation expectations play a huge role.

They do not think that a rise in the quantity of money leads to inflation but a shift in market participants' inflation expectations. According to their argument, rising inflation expectations lead to higher inflation because market participants advance consumption expenses since they expect prices to increase further.

Although this sounds very reasonable, there is a problem with that theory because nobody will buy more goods and services as intended because of a rise in inflation expectations. Nobody will turn up the air conditioner more because one expects electricity prices to rise, and nobody will rent an additional home because his rent increases. The only place where expectations play a role is in asset markets, but they do not have much to do with the CPI.

Another argument for why inflation is high is that it is because of the problems in the supply chain and the rise in energy prices. However, what is overlooked is that this would only lead to relative price changes without an overall increase in the quantity of money.

That can be demonstrated beautifully with the current situation of very high energy prices. One month ago, I wrote that there is some evidence that despite the considerable pick up in prices, fuel consumption did not decrease. For example, people need to fuel their cars to go to work, and they cannot easily switch because prices are high.

If market participants can only spend a certain amount of their income on consumption and pay more for one good, prices for other goods need to fall until a new equilibrium is reached. As a result, the exchange ratio between those goods changes, but the price level remains unchanged. It is only the experience that economists made during the last decade (because they do not look at asset prices) that they think this is not the case.

However, they may have a point over the short term, and disequilibria could emerge because the world economy is no quantum computer that adjusts in real-time. Over the medium term, the prices will have to adjust, though. If a merchant cannot sell at a certain price, she needs to lower it.

I want to add that central banks have gained a lot of political influence since the GFC. That is especially true for the ECB, which has discussed how monetary policy could support the green transition for a while now, although this would mean another market intervention. Further, I still would question the idea that this would lead to higher economic growth. In fact, the results of the last decade let us assume that the opposite would happen.

That brings me to another point, why inflation did not rise in the 2010s. The money supply rose before the pandemic because governments increased deficit spending to spur growth and grow out of the crisis. But the state is a lousy entrepreneur; thus, many government expenditures were made on unproductive projects, and the money did not reach the real economy.

Additionally, artificially low-interest rates kept unproductive businesses alive and bonded resources. As a result, the QE policies more likely hindered growth instead of spurring it. For example, the number of unproductive firms in the Russel 3000 has more than doubled since 2010.

That also has consequences for businesses’ creditworthiness. In the current environment of rising rates, credit spreads have risen to dangerous levels of previous crises. Probably it is not enough that the ECB only buys government bonds from the PIGS.

Further, the current energy crisis shows that a lot of mistakes were made by politicians as well. The policies to boost renewables and plans to forbid fossil energy like coal and oil lead to a fall in investments in those sectors. Because of that, we are now facing a lack of additional capacity. As governments now try to reactivate coal to fight the energy crisis, one can expect that coal prices will pick up too.

As the ECB is already thinking about another QE program (ok, I admit, it will not be labeled QE and will have a fancy name), it is impossible to check out the monetary roach motel. But, as inflation has already risen, it will be much harder to fight the coming recession with another loosening of monetary policy without causing another, more extensive inflation wave.

That brings me to the final part of this week’s article, where I look at the potential effects on markets. I still think that the euro will fall further against the dollar and that it is a question of when not if parity is reached.

The Fed is still saying that it will not stop hiking interest rates. Thus I also expect that the low in stocks is not reached yet and that buying the dip will remain risky, although, if timed appropriately, one could probably sack in some profits in some bear market rallies. However, my feeling is that we are still far from away from the capitulation phase.

As I noted a few weeks ago, recession fears can cause a setback in commodity prices, leading to a pause in rate increases on the long end of the curve. Nevertheless, I am unsure if this marks the top in longer-term rates.

If the setback in commodities continues, we can also assume that currencies of commodity-rich emerging markets will get under more pressure too. The dollar remains the currency of choice in times of uncertainty, while gold and bitcoin additionally suffer from positive real yields.

The current situation does not suggest that the energy market will calm down, despite the recent slowdown in German inflation. The setback in the inflation rates can be explained mainly due to political measures to dampen inflation.

Recent statements from ECB officials do not suggest that the central bankers have learned anything from the mistakes they made under Draghi. One can expect that the ECB will become more political in the future. The argument that this is important in times of crisis will speed up this process, I fear, mainly because we cannot expect that the economic war between the West and Russia will end soon.

Somehow it is a bit amusing that the economic war with Russia could lead to a more active ECB. John McCain once said that Russia is a gas station masquerading as a country. The same could be said about the ECB, which has increasingly become a political arm of the EU masquerading as a central bank.

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! You can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox if you like what I write. Also, it would be fantastic if you shared it on social media or liked the post!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity.)