The horizon of many people is a circle with a radius of zero. They call this their point of view

-Albert Einstein

The attitude of most people, us included, is shaped by the environment they live in. That might be the reason why the views of people living in the countryside differ in many ways from those who live in the cities.

Yet, no one should be surprised. Usually, people in the countryside mostly know each other at least a bit, while there is much more anonymity in the jungle of the big city. While in the countryside, most people own their own homes, most people in the towns rent a flat, and one only moves in his circle of friends. About the reality of the life of others, you only notice little.

That might be one of the reasons why people in the cities feel some sort of antipathy against people from the countryside and often accuse the other side of not understanding each other.

But that is not only about people in the cities and the countryside. The same phenomena can be observed among people with different life realities. Our views are vastly shaped by the echo chambers we live in.

Birds of a feather flock together, and so many can only assume what the reality of people outside their bubbles really looks like. Most of us struggle with that and have problems understanding different realities. Within the anonymity of the city, low-income groups mostly stay among themselves. Business owners are in their circles, while artists and intellectuals discuss life's meaning. In the countryside, these groups have many more boundary points, like kids attending the same schools. Everything is organized far closer to the origin of the human species, where humans lived in small groups and were more interested in the forthcoming of each other because it could matter about future life or death.

The ongoing exclusiveness within our modern society, either professional or private, caused some groups to quickly dismiss advice from the outside with the notion that the sender does not have the slightest idea of what he is talking about.

One can easily observe that kind of behavior among academic economists. At universities, economists are not just economists. They are much more specialized. There are micro economists, macroeconomists, labor economists, health economists, specialists for international trade, economic history, and so forth.

Many prefer to have discussions only with like-minded colleagues. Beware of a labor economist coming forward and talking about macroeconomics, and beware even more if the person is from outside the academic world. Quickly, specialists come around to reply that the opinion is not worth to be discussed because the person has published nothing in this or that specific field.

Something like that has occurred to German economist Isabella Weber, who has received much attention from journalists throughout the US and Europe. I believe it was at the end of last year when she published a piece about whether the state should not come forward and put price controls into place to throw that argument into the discussion about inflation. Quickly, the creme de la creme of economists came forward, trying to shut down the debate by calling the argument stupid and crazy.

One can conclude that the pushback drove even more attention from the media to Mrs. Weber. Some time ago this year, Weber, who works at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, published an article (with her colleague Evan Warner) discussing the thesis that the current inflation is mainly profit-driven (sellers inflation).

Again, the article got much attention from the financial press, but other academics started criticizing her ad hominem. For example, one economist on Twitter has asked why the media did not talk to someone who knows the subject, as Weber has never published anything on inflation before that.

It would have been better if this economist (and others) had discussed the theory and why it should be dismissed. In my opinion, the notion that a person has never published anything on X is not proof enough to dismiss a thesis. Debates are even more important and thought-provoking, especially if it gives another perspective on the subject.

Weber's article is titled Sellers’ Inflation, Profits and Conflict: Why can Large Firms Hike Prices in an Emergency? The article was published timely near to a paper by Blanchard and Bernanke, who found that wages have not driven the current inflation but spiking commodity and raw material prices, combined with supply bottlenecks in some sectors.

Another paper from Bianchi et al. finds that current inflation was mainly driven by fiscal spending. Although fiscal spending has fueled the economic recovery, they say, it has also fueled inflation.

Weber et al. throw another theory into the discussion ‘What has caused the current inflationary spike?’. As I mentioned, the article received a lot of attention, so maybe one should look closer.

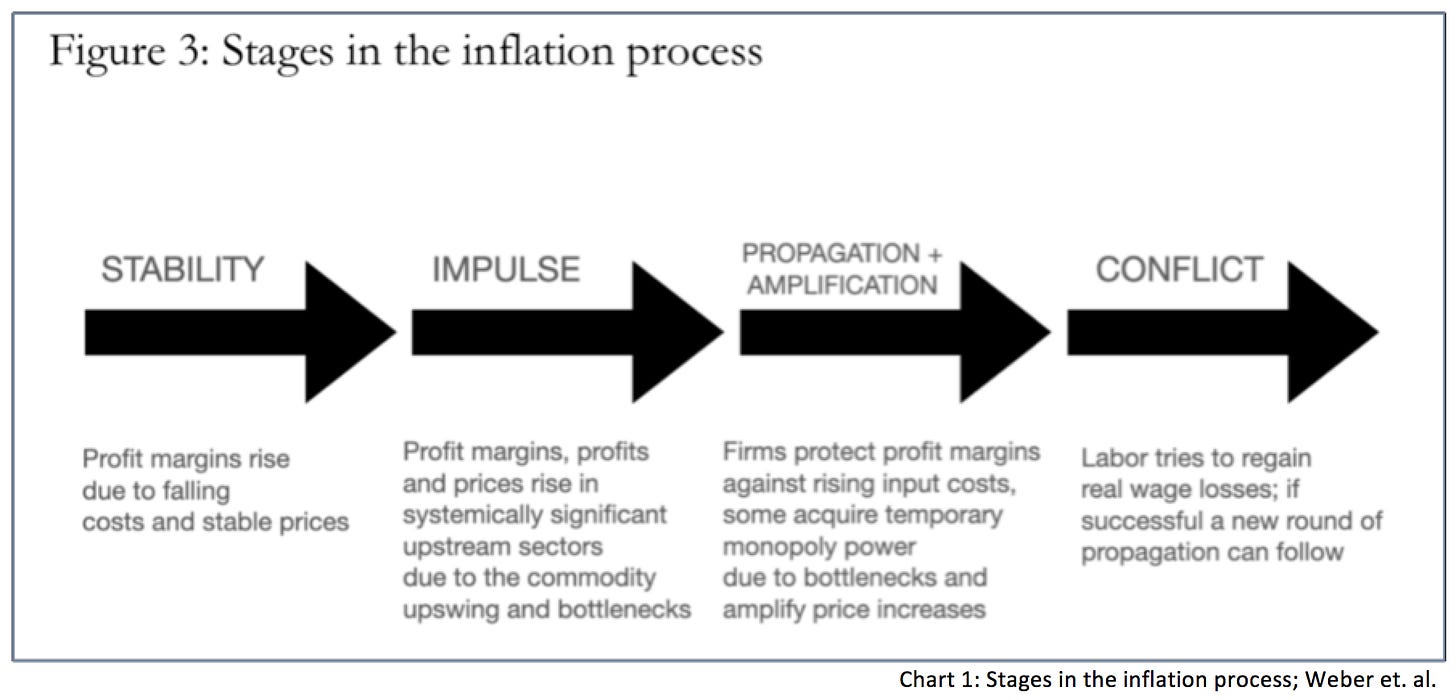

In the working paper, Weber and Wasner look at the influence of businesses’ profit margins on inflation in the tradition of the work of leftist economist Abba P. Lerner (1903-1982). They split the current rise in inflation into three phases, on which they want to show how profit margins are causing inflation.

After prices remained relatively stable and profit margins rose due to falling costs during the 2010s, an impulse in the third quarter of 2020 led to a rise in commodity prices and supply-chain bottlenecks for critical inputs accompanied by a fall in total output, so the authors say.

Further, they argue that firms took advantage of the current situation by pursuing a monopolistic price-setting policy, meaning they raise prices more than they would need, something they would not have been able to do normally. Allegedly, these price shocks then spread through the whole value chain. They call this the propagation + amplification phase.

Finally, there is the third phase, where it comes to conflicts between businesses and workers because while firms were able to increase profit margins, real wages fell. In this phase, workers are trying to negotiate higher wages to compensate for the loss in real purchasing power. The authors describe this as a form of distribution conflict, where workers try to get their fair share of profits again.

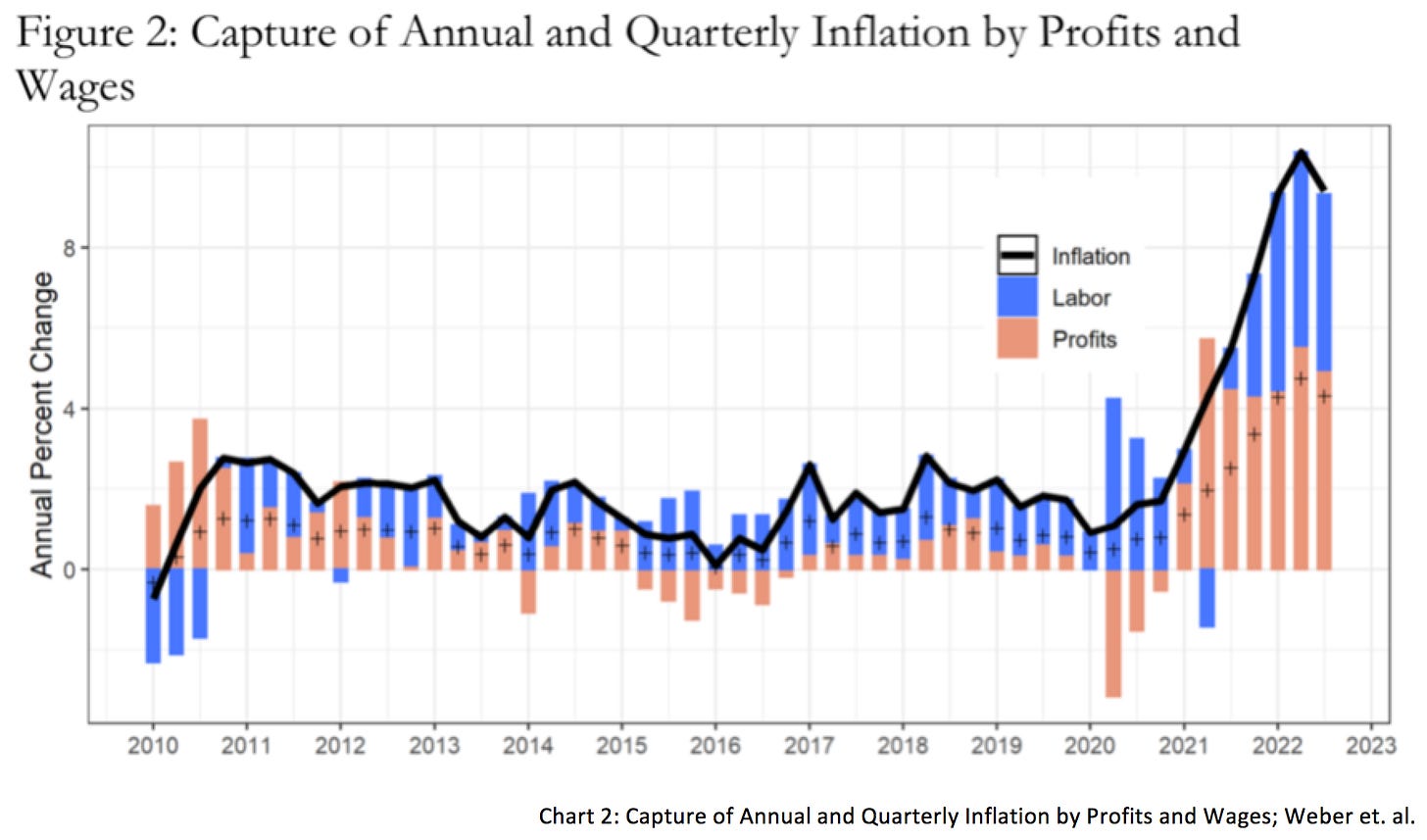

On the aggregate stage, Weber et al. find that profit margins rose faster than wages, which means that businesses have increased prices more than they needed to if they had intended to keep their profit margins constant.

On the micro stage, the authors looked into a series of earnings calls from US companies within the oil, chemical, iron and steel, soft drink, and meat companies, to name a few. Many of those firms increased their profit margins after the pandemic. With those transcripts, Weber and Wasner try to confirm their thesis.

Probably the pushback from academic economists is about the propositions within the article. Weber and Wasner propose that the state should be more proactive during multiple shocks and compare it with happenings during World War 2, where the US implemented various price controls to keep inflation subdued. They support more government intervention in those times. Like Keynes, they suggest a buffer system like the Strategic Petroleum Reserve so that the state can bring down market prices. Of course, they point to Weber’s proposition for the German gas price break, which is probably inspired by Weber’s suggestions (although German economists say that the implemented version is not what Weber proposed).

First of all, what Weber and Wasner show in the paper is how price inflation is making its way and spreading throughout the economy. Unlike another theory (and Blanchard and Bernanke find that, too), workers are at the end of the inflationary chain and want higher wages that make up for the loss in purchasing power. It shows that businesses raise prices to increase their profit margins under certain conditions that more than make up for the increase in their costs.

I think that Isabella Weber’s paper is not uninteresting in the discussion. But it is also true that Weber and Wasner, just as Blanchard and Bernanke and Bianchi et al., more or less ignore the variable of the money supply within their analysis. They agree that the money supply has no significant influence on inflation, a thesis that became extremely popular after 2008.

Nowadays, many academic economists believe that economics is a science where statistics, or econometrics, is more important than theory. But whether it is rising commodity prices, higher profit margins, or increasing wages, all of which were identified as causes of current high inflation, are just a result of the expansion of the money supply.

In theory, when there is a constant supply of money, there cannot be a rise in the general level of all prices just because the price for one good goes up, ceteris paribus. Consider an economy with two goods: if the price for good A goes up, the price of good B has to fall. The only scenario where prices could rise if the money supply remains constant is if production levels fall.

If money is put out of the system of the real economy and saved/invested into paper assets, it drives up prices there, but the effect on consumer prices remains relatively small. If the demand for financial assets falls and people sell them to buy consumption goods, that, on the other hand, can drive up consumer prices.

Yet, if money demand decreases, people quickly spend their earned money and exchange it for goods. This will drive the value of money down and prices for other goods up. However, this effect is finite if the money producers (in our world, central banks and commercial banks) do not expand the money supply.

In the current case, the money supply expanded first, and fiscal transfers pushed it into the economic cycle, where falling supply met constant demand. Profit margins rose faster than costs because businesses expected continuously increasing prices and wanted to secure margins. In the end, wage earners, as Weber and Wasler correctly observe, try to catch up for their initial loss in real wages.

The problem of macro-econometric analysis here is that the pace and development of how these effects play out depend strongly on human behavior. One must fail if one wants to pour a complicated, dynamic system like the economy into a static model. Developments are highly dependent on changes in human behavior, meaning that economic science can merely spot generally correct developments but cannot calculate or forecast the future.

That might be a reason why it is so hard for econometrics to spot a relationship between money supply growth and consumer price inflation, as it could take long time frames or, like it was after 2008, the growth of the money supply could be absorbed by asset markets and hardly cause any consumer price inflation. Yet, if money flows back from financial markets into consumer goods markets, this can lead to another inflation spike, although the money supply did not rise further.

A similar phenomenon can be seen when we look at current analysis from analysis and economists, who repeatedly call for a recession of the US (or world-) economy. This caused many market participants to stay defensive, resulting in their PnLs now being in negative territory.

Even as rising interest rates, tighter credit conditions, an inverse yield curve, and shrinking manufacturing point to an imminent recession, consumption remains relatively strong, and wages and the unemployment rate remains remarkably resilient.

On the other hand, rising credit card payments might hint that consumers will have to cut back on consumption soon, which would cause a recession. However, the monthly ratio of credit/debit cards is back below pre-pandemic lows, as Bank of America recently noticed. That is also true for lower and middle-income groups, thus suggesting continuous resilience.

Within the last weeks, the US labor market cooled a bit, although just slightly. Many bears see this as an indicator that the recession is finally imminent. Yet, this contradicts the data we see from consumers. Many now point to the Sahm rule, named after its creator, Claudia Sahm. It says that a recession usually starts when the three-month unemployment rate average is about 0.5 percentage points above its 12-month low.

Sahm recently published a Twitter thread about those two topics. For a while now, she has been pointing to the fact that excess savings cause the resilience of the US consumer. The top 20% percentile owns about 50% of those excess savings. That means that the small group of the wealthier is responsible for the vast majority of total consumption. A recession can only occur if these rich people also cut back on consumption.

The wealthy never received stimulus checks, but I would add that they benefit from them as well. Fiscal transfers raise the recipients' income and spread from recipient to recipient until they are no longer spent on consumption but invested in financial markets. According to economists, this could take a couple of years.

Sahm’s second Twitter thread deals with the Sahm rule, where she breaks it down from the national to the state level. Afterward, she looks at the most populous states with the highest population and compares it with the national level over time. She notes that the indicator can be quite volatile for low-populous states.

Of all the highly populous states, California is the only one where the Sahm rule points to a recession. Yet, Sahm notes that some rebalancing of the tech sector might cause this. Further, she adds that the indicator should not be seen as a tool for forecasting. The labor market still does not indicate a recession but is signaling strength.

I may repeat myself here, but it is always tricky to forecast the time of specific events, although I believe that Europe and the US will both have to deal with the consequences of a hard landing on their economies. And that is the crucial question: when will it happen? Market sentiment also plays a role here, especially regarding the positioning of financial market participants.

And positioning points to further room for equity indices, in my opinion. I also expect the sell-off in bonds to continue further. Regarding European soil, neither the ECB nor the Bank of England can think about ending the rate hiking cycle like the Fed did this Friday.

A pause poses some dangerous risks. If central banks pause and monthly core inflation suddenly picks up, what follows might be a panic reaction from the pausing central bank. With regards to the shrinking money supply, this might increase disinflationary pressures afterward and lead to a wash-out in bonds.

You’re trying to take me, you’re trying to make me,

This is the only, give me the only thing.

I’m tired of trying, I’m tired of lying,

The only thing I understand is what I feelStatic X - The Only

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! If you like my writing, you can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox. Also, sharing it on social media or liking the position would be fantastic!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice. I may change my view the next day if the facts change)