The American Nightmare

Every worthy act is difficult. Ascent is always difficult. Descent is easy and often slippery ― Mahatma Gandhi

In recent years, Isabella Weber of the University of Massachusetts Amherst has gained significant attention in media outlets such as The New York Times, The Guardian, The Financial Times, Bloomberg, and many others. Her work has also been widely celebrated in left-leaning intellectual circles worldwide, resulting in numerous invitations from progressive political parties.

The reason for this surge in attention is her theory of inflation. According to Weber, inflation has been predominantly "profit-driven," meaning that rising prices are primarily due to market concentration and companies raising prices to increase profits at consumers' expense. Media outlets have coined this the "greedflation" theory.

Despite the media enthusiasm, various academics have critically challenged her theory. Yet Weber has not directly responded to these critiques, opting to publish article after article reaffirming her theory (I’ve written my critique from an Austrian economics perspective, refuting her theory).

It’s worth noting that Weber’s ideas are neither groundbreaking nor new; they echo themes long circulated in leftist, MMT, and Post-Keynesian economic circles, which often attribute economic issues to corporate greed. Similarly, her proposed solution calls for increased government intervention in markets.

Just this week, The New York Times published yet another opinion piece by Weber, in which she reiterated her theory and solution. She argued that the "absence" of government within the economy has exacerbated economic problems, which she claims ultimately led to the recent election victory of Donald Trump. In an interview, she even suggested the need to "think seriously about Anti-Fascist Economics."

Unsurprisingly, her recommendations boil down to more government control over various markets, such as establishing "buffer stocks" to stabilize consumer prices. For example, she suggests that the government should sell oil when prices rise and buy oil when they fall. Beyond oil, she argues this approach should extend to critical minerals to foster green supply chains and food staples. One of the most revealing lines in her recent New York Times opinion piece is: "We need policies that align public and private interests with resilience."

However, while private interests are straightforward, this raises the question of who defines "public interest"? Presumably, Weber’s answer is "elected officials" and "experts." According to her, the government and its experts should direct companies on what to produce, store, and charge to safeguard stability. She argues this is essential in an "age of overlapping emergencies" and warns that not adopting such policies "should serve as a warning to democratic governments" [emphasis mine].

While it’s likely unintentional, Weber’s argument edges close to the philosophy of fascism as defined by its founder, Benito Mussolini, who described it as "the merger of corporation and state." Moreover, as incentives shape political actions, policies granting such power may create or exploit states of emergency to expand government authority.

When Weber and other prominent left-leaning figures advocate policies that echo those of authoritarian regimes as a means of "preventing the rise of fascism," they appear to lack historical perspective. They overlook the risks inherent in giving politicians more extraordinary powers and disregard the potential dangers of expanded government influence. If their conclusion on why Trump won the election is that government intervention should be increased, it’s deeply flawed.

Following Trump’s decisive victory over Harris last week, numerous statements about potential and confirmed candidates for key government positions have been made. I’ll delve into these later when discussing the potential economic implications of Trump’s declared goals and what we might expect from the initial appointments affecting the US economy.

Unsurprisingly, the US stock market responded positively to Trump’s win. My expectation that small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) would be the primary beneficiaries is supported by the performance of the Russell 2000 index, which has outpaced the Nasdaq and the Dow by more than 1% since the election. In contrast, European stocks saw no such boost and have dropped below their November 5 levels.

With Elon Musk playing a prominent role in Trump’s campaign, Tesla stock saw a significant jump, gaining over 30% since November 5—outperforming even Bitcoin, which has risen more than 25% as markets anticipate more crypto-friendly US policies and potentially even a Bitcoin reserve.

Gold, which has seen substantial gains year-to-date, has reacted less favorably to Trump’s win, dropping about 5% since Election Day. This decline likely correlates with rising bond yields, which spiked on election night before leveling out and trending upward.

The election wasn’t the only major event last week; the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) also met a day later. In addition, S&P Global Composite and Services data and ISM Services figures for the US were released, indicating that the economy remains expanding.

Thursday’s jobless claims underscored the continued strength of the US labor market, with no significant signs of weakness. Consumer sentiment from the University of Michigan showed a slight miss on current conditions but beat expectations and remained in its upward trend since 2022. Overall, these reports offered no surprises that would alter my assessment of the current US economic landscape.

Turning to the FOMC meeting, the committee lowered the federal funds rate by 25 basis points as expected. However, as usual, the press conference was the main event, with markets keen to hear Jay Powell’s take on recent economic developments, especially in light of sharply rising long-term interest rates since the 50 basis-point rate cut in September.

In his opening statement, Powell provided no new insights on this issue. He confirmed that the US economy continues to expand, with resilient consumer spending, strengthened investment, and stable—albeit slightly less tight—labor market conditions compared to last year. With inflation gradually decreasing, Powell emphasized the Fed’s focus on balancing its dual mandate of full employment and price stability.

As always, the Q&A session of the press conference was more engaging than the opening remarks. One point that stood out to me was Powell’s response to Nick Timiraos of The Wall Street Journal. Powell stated that long-term interest rates are “nowhere near” where they were a year ago but with rates only 50 basis points lower than a year ago, describing them as “nowhere near” may be somewhat of an exaggeration.

On the other hand, Powell admitted that it’s too early to determine where long-term interest rates will ultimately settle. While his response suggests he doesn’t foresee much additional upside for longer-term rates, he emphasized that the FOMC will assess incoming data to provide a more precise outlook later. I gather that Powell has repeatedly conveyed that the Fed considers current rates restrictive and significantly above the neutral level. He has indicated that interest rates will eventually need to move toward a "more neutral stance."

That brings me to a question I’ve pondered for some time: the Fed’s assertion that interest rates are restrictive and above neutral. It would be far more helpful if Powell or the Fed provided guidance on where they estimate the neutral rate to be. However, like other Fed officials in recent months, Powell reiterated this point during the press conference without offering specifics. I found it striking that he remarked the Fed "feels that [interest rates] are restrictive."

Two weeks ago, I quoted former Fed governor Kevin Warsh, who expressed skepticism about the Fed’s claims of restrictiveness. Although inflation has cooled, growth remains strong, and unemployment is still near historic lows. Credit spreads aren’t widening, and stock markets continue to hit new highs. Aside from a relatively weak housing sector, there’s little data to support the notion that current yields are actually restrictive.

Warsh made a comment in that interview that resurfaced in my mind as I read the FOMC transcript:

There's a series of risk free that are competing with the Treasury. They come from Fannie and Freddie, they come from home loan banks, they come from government guarantees, all sorts of things.

This comment also reminded me of an argument by George Robertson, a former US Treasury bond trader at Morgan Stanley. Robertson has argued for some time that the US 10-year Treasury yield is not the true risk-free rate and that Treasuries actually trade below it. He suggests that the true risk-free rate can be inferred from the 30-year mortgage rate, which is also perceived as relatively “risk-free.”

I had previously dismissed this idea, partly due to uncertainty around his economic rationale and skepticism that the market could misjudge this on such a scale. However, given my argument that long-term rates in the US could rise further—and my growing belief that the neutral rate might indeed be higher—I decided to revisit Robertson’s theory.

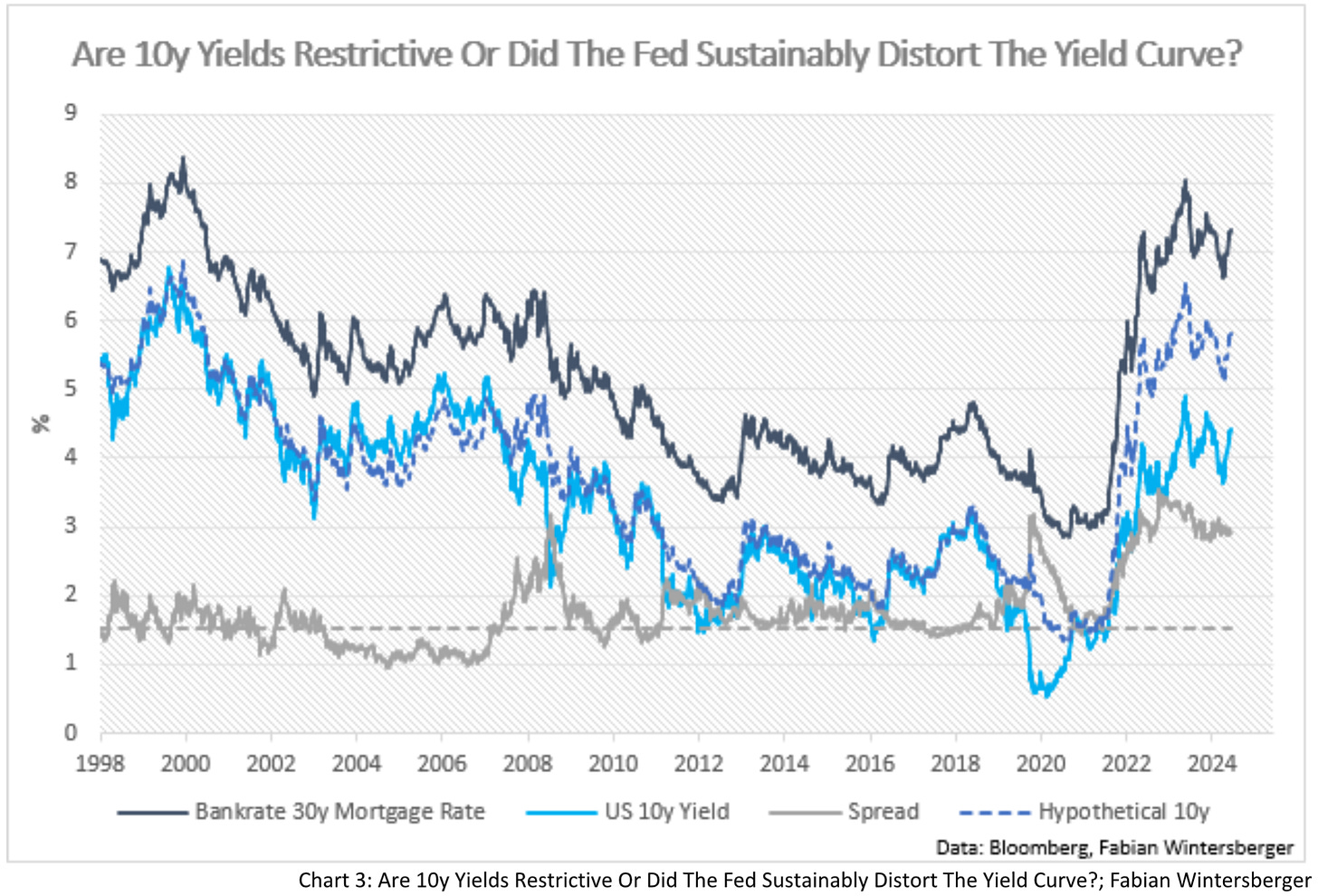

My approach here is straightforward, though Robertson probably calculates it differently. I looked at the historical spread between 30-year mortgage rates and the US 10-year yield, noting that before the Fed’s QE initiatives, this spread was narrow, only widening during economic downturns. By taking the pre-QE average spread and subtracting it from the 30-year mortgage rate, I derived a hypothetical 10-year yield.

I found that this “hypothetical 10-year yield” closely tracked the actual 10-year yield until late 2021, apart from during economic crises. However, from the end of 2021, when the Fed began a more hawkish stance, the actual 10-year yield rose less than this hypothetical yield.

Based on this, I believe long-term rates in the US could still rise to the 5.5–6% range before they become restrictive for the US economy. Critical factors like the US deficit, Trump’s proposed tax cuts, and the potential easing of the federal funds rate support this outlook. My thesis remains that the neutral rate is higher than the Fed estimates and that current policy is not restrictive but relatively accommodative for economic growth.

Furthermore, US CPI data released this week supports a point I made two weeks ago—that the Fed’s monetary expansion and “helicopter money” policies from the past two administrations have distorted the traditional timeline between money supply changes and inflation. Although I still expect inflation to ease gradually, I see a rising risk that the recent growth in money supply could counter this trend, potentially driving inflation higher by late 2025.

This week’s CPI data aligned with forecasts, with annual CPI rising from 2.4% to 2.6%, while core CPI held steady at 3.3%. A year ago, the Fed designated “Supercore” CPI as its favored inflation metric, and as of now, it remains almost double its pre-2020 levels.

Real average weekly earnings also rose by 1.4% year-over-year, suggesting support for consumer spending going forward. The NFIB Small Business Optimism Index also improved this week, indicating positive sentiment among small businesses and steady labor demand, though uncertainty remains elevated.

In summary, the data supports the argument that the US economy shows no immediate signs of weakness. The Fed is still expected to reduce interest rates by 25 basis points next month, with more than three additional cuts anticipated by the end of 2025. Given this backdrop, maintaining a bearish stance on the US economy is challenging.

Finally, I want to assess the potential implications of these factors for the short-term outlook in financial markets, as well as how policies under the upcoming Trump administration might affect markets going forward. In my view, some points could catch many market participants off-guard, although this remains uncertain.

The dollar has appreciated strongly this week, with yields also rising since the election. However, sentiment suggests that positioning has become a bit crowded. Additionally, the euro’s recent weakening may boost short-term economic activity in the Eurozone. While sentiment and positioning alone don’t necessarily indicate an imminent dollar depreciation against other major currencies, a pullback wouldn’t be surprising.

Recent price action in gold offers insights into such potential short-term dynamics. Gold has surged over the past several months, with increasingly bullish forecasts circulating in the market. We’ve seen growing enthusiasm as more people turn bullish on gold, leading to stretched positioning.

However, expected real 10-year yields have been climbing sharply since early October, posing a potential headwind for gold from a fundamental standpoint. Combined with this bullish stretch in positioning, it appears some investors have started to take profits. While gold’s decline could continue in the short term, the $2,300 level may serve as a support zone where prices could rebound—but nothing is certain.

In light of this, a short-term correction in the dollar and US interest rates is possible before they resume their upward trends. Especially in the case of yields, we would need to see confirmation that the uptrend is broken before turning bullish on bonds, and that’s not the case at the moment.

As for the stock market, particularly in the US, the outlook is less certain. The post-election euphoria has pushed market sentiment extremely high, which doesn’t suggest a favorable risk-reward for remaining bullish, yet being bearish also feels unwarranted. At this point, I’d say the chances of a continued rally or a pullback are about equal.

In the medium to long term, the Trump administration could impact the US economy in ways not yet fully anticipated. This week, Trump announced the creation of a “Department of Government Efficiency,” to be led by Vivek Ramaswamy and Elon Musk, with the goal of "cutting excessive regulations, reducing wasteful spending, and restructuring federal agencies."

While the immediate impact of this new department is still debatable—given that most government employees aren’t federally employed—it’s worth considering the potential effects. While freeing up human capital for the private sector might have positive implications in the medium to long term, I suspect the short-term impact could be pretty disruptive.

Although regulatory cuts generally stimulate economic activity over time, they must navigate the political process, obtain approval, and then undergo implementation. Conversely, laying off government workers would immediately raise the unemployment rate, while cutting federal spending would halt certain current economic support mechanisms.

While private sector reallocation of these resources may ultimately enhance productivity, the required economic restructuring could cause short-term economic pain. The extent of this pain will depend on the scale of these reforms, but sharp changes could lead to a significant economic slowdown before any sustainable growth takes hold.

It will be interesting to see whether the administration will remain committed to these plans or back off if they face backlash. Rather than reviving the American Dream, there’s a risk that, if not carefully managed, these changes could turn into The American Nightmare.

I'm the American nightmare, with American dreams

Of countin' the bodies while you count sheep

I'm the American nightmare, yeah, I'm living' the dream

I'm slashing my way through the golden age of the silver screamIce Nine Kills – The American Nightmare

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for taking the time to read! If you enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to receive each post directly in your inbox. Additionally, sharing it on social media or giving the post a thumbs-up would be greatly appreciated!

All my posts and opinions are purely personal and do not represent the views of any individuals, institutions, or organizations I may be or have been affiliated with, whether professionally or personally. They do not constitute investment advice, and my perspective may change over time in response to evolving facts. IT IS STRONGLY RECOMMENDED TO SEEK INDEPENDENT ADVICE AND CONDUCT YOUR OWN RESEARCH BEFORE MAKING INVESTMENT DECISIONS.

excellent writeup Fabian, and I think mostly spot on. one thing to consider about the Trump plans for efficiency, though, is that he is not running for re-election, so may be willing to absorb some pain to achieve longer term goals. just a thought. and I have read and come to agree with Robertson's views on the risk-free rate over the past months. I think it makes a lot of sense and demonstrates the impact QE has had, which is not merely lowering rates, but confusing the Fed itself