I was making almost minimum wage on "The Young and The Restless." But it was my first job, so I accepted my first quote. I had a great time on it, and it obviously led me to better things. – Eva Longoria

A quarter of a century ago, on April 01, 1999, the United Kingdom introduced its first national minimum wage. The Blair government and other proponents celebrated it as a groundbreaking achievement that would help to ensure more social justice within society and as a support for the most vulnerable in the jobs market.

While it has to be noted that job markets around the Western hemisphere are mostly anything but free-market organized due to collective bargaining by trade unions and corporatist networks, the minimum wage law was simply just a continuation of these policies.

A higher wage for those who earn the least sounds like a good idea at first. However, if we recall one of the great social philosophers of the 19th century, Frederic Bastiat:

In the department of economy, an act, a habit, an institution, a law, gives birth not only to an effect, but to a series of effects. Of these effects, the first only is immediate; it manifests itself simultaneously with its cause — it is seen. The others unfold in succession — they are not seen: it is well for us if they are foreseen. Between a good and a bad economist this constitutes the whole difference — the one takes account of the visible effect; the other takes account both of the effects which are seen and also of those which it is necessary to foresee.

Minimum wages are not different in that sense. The political proponents support what is "seen" as the direct consequences of the policy, namely higher wages for those who earn a salary below the set minimum. They think this improved the situation while totally neglecting the consequences that follow, what Bastiat called the "unseen.”

Those who suffer from these laws are primarily the young, who are at the beginning of their working careers. Indeed, after the UK laws were introduced, what followed was a rise in youth unemployment:

These policy trends of the past 17 years have led to a situation of growing youth unemployment. It has been rising consistently since 2001, despite a growing economy. "In the last 12 years, the number of 18 to 24-year-olds who are out of work has risen by 78 per cent, while unemployment across all age groups has increased by 42 per cent."

It's obvious why labor unions favor a minimum wage: Their members are already employed. People with no experience who would need training on the job to improve are now kept out of the labor market because businesses can't afford to raise them.

Interestingly, the history of minimum wages in the United States shows that a primary goal of some of the minimum wage proponents was to protect their interest groups from competition from the lower-skilled. While this narrative has entirely disappeared, the results are still very similar.

By April 1, California had raised the minimum wage to 20 dollars, a four-dollar increase. As a result, the fast food companies, who traditionally employ many low-skilled workers, announced job cuts:

Fast food workers are losing their jobs in California as more restaurant chains prepare to meet a new $20 minimum wage set to go into effect next week...Multiple businesses have plans to axe hundreds of jobs, as well as cut back hours and freeze hiring, the report shows.

California will, therefore, be another example where the raised minimum wage will lead to economic misery for those who should benefit from it. Although the intentions of the people who support a higher minimum wage are primarily good-will, the outcome clearly isn't. However, as Thomas Sowell once rightly said:

It is usually futile to try to talk facts and analysis to people who are enjoying a sense of moral superiority in their ignorance.

Regarding the prevailing sentiment in financial markets, there appears to be little concern regarding potential headwinds in the US labor market going forward. On the contrary, most assessments I've come across suggest that the economy will continue to outperform expectations, with interest rates deemed non-restrictive and expectations for high growth and inflation.

Discussions have been abundant regarding the disparities between Non-Farm Payroll (NFP) numbers from the establishment and household surveys, with various attempts to explain these differences. Minding price movements within financial markets, strong NFP numbers are favored, indicating a scenario of no slowdown and an expectation of sustained high interest rates.

Recently, Bloomberg economist Anna Wong shared a chart highlighting potential underestimations of labor market troubles by market participants. Wong emphasizes the significance of this chart, suggesting that despite the flaws in the household survey, once it indicates a turn, the market tends to follow suit.

While I wouldn't assert immediate weakness in the US labor market, a degree of caution seems warranted. Moreover, it's curious why there's such fixation on the labor market as a harbinger of economic weakness, considering it typically lags behind other indicators.

Regarding initial jobless claims, which remain at remarkably low levels, Wong presented another intriguing argument this week concerning the assertion that immigration is propelling economic expansion.

If you also believe that immigration drive hiring the last two years, then you should also believe that those won’t have long enough work history to be eligible for unemployment benefits were they be laid off.

This implies that unemployment figures could still rise while jobless claims may not increase. If these individuals are laid off, they may not qualify for unemployment benefits due to their limited work history.

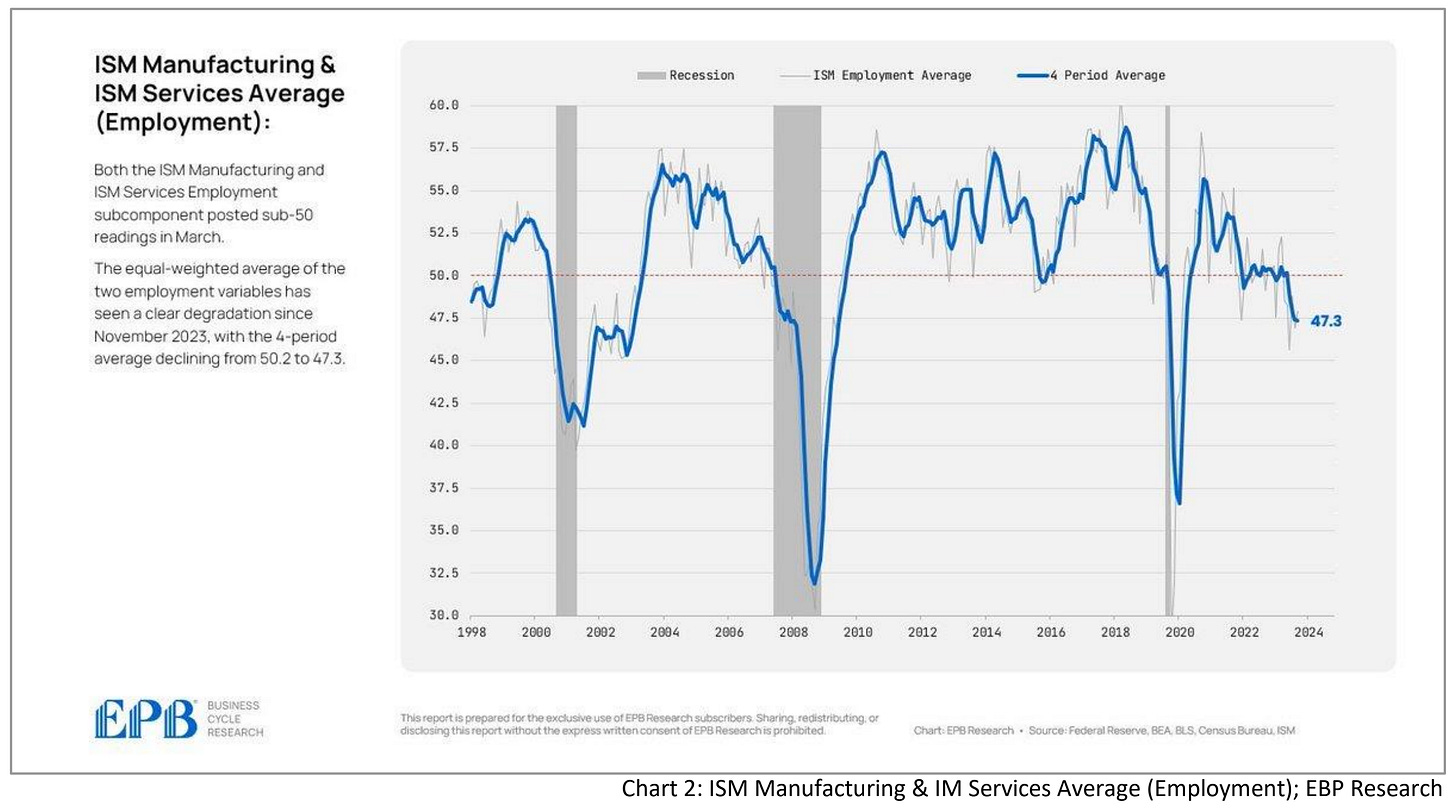

Further indications of a potentially cooling labor market are evident in the ISM report, where the employment subcomponents register below 50. According to EBP Business Cycle Research: "The equal-weighted average of the two employment variables has shown a clear decline since November 2023, with the 4-period average dropping from 50.2 to 47.3".

While the stock market continues its "honeymoon phase," pursuing new highs, interest rates are currently fluctuating within a broad range, highlighting growing uncertainty about the economy's future trajectory. Nevertheless, the recent ADP report emphasized that signs still point to a robust labor market, noting that annual pay increased by 5.1% this week.

While markets were closed on Good Friday, Jerome Powell delivered a speech at a conference at the San Francisco Federal Reserve, essentially reiterating his longstanding views:

...Powell said he still expected “inflation to come down on a sometimes bumpy path to 2%.’' But the central bank’s policymakers, he said, need to see further evidence before they would cut rates for the first time since inflation shot to a four-decade peak two years ago.

When markets reopened on Tuesday, bonds experienced a significant sell-off, with the US 10-year rising above 4.3%, marking the highest reading since December. Conversely, 10-year Bund yields failed to reach another year-to-date high, currently hovering around 2.38%. I'd assume that this is because assessments regarding future inflation are diverging in the Eurozone and the US.

Friday's PCE numbers came in line, with a 2.5% increase YoY, slightly up from last month's 2.4%, but personal spending surprised to the upside. On the other hand, CPI numbers in Eurozone countries surprised to the downside. EU harmonized consumer price inflation in Italy was 1.3% year-over-year, HICP in France dropped from 3 to 2.3% (est. 2.6%), and HICP in Germany came in at 2.3%.

This supports the assumption I've held for quite a while now, namely that the ECB will likely cut interest rates before the Federal Reserve. Furthermore, the more I consider the facts, the more convinced I become that consumer prices inflated more in the Eurozone than in the US due to supply and demand imbalances resulting from the outbreak of the war in Ukraine and the restructuring of energy supply chains, driving some prices to unsustainable highs. That could partially explain why inflation peaked higher in Germany than in France.

After all, it was still the growth in broad money supply that drove inflation, and continuously, money supply is not considered a variable for mainstream economists and analysts to assess the future path of inflation. But regardless of one's perspective, the recent inflation numbers in the Eurozone support the assumption that the ECB will reduce interest rates in June at least.

The debate about the future path of inflation in the United States remains more complicated, especially when considering the development of commodity prices. For example, oil (WTI) has risen 18% year-to-date, US gasoline is up 30% year-to-date, and copper is also up 8.22% this year, suggesting growing global industrial demand.

Nevertheless, I continue to argue that this is just a change in relative prices rather than a re-acceleration of average prices and that inflation will drop below the Fed's 2% goal later this year, similar to what will happen in the Eurozone.

However, rather than interpreting this as imminent economic weakness, I'd assert that the relaxing inflation pressure could initially offer some economic relief, which could support the stock market. European PMIs this week point to an expanding economy, at least for the short term.

It's important to note here that this is a direct result of the continuously strong consumption in the United States. The global economic structure is such that Europe and Asia are producing the goods while the Americans are consuming them, exporting dollars, which are then recycled in demand for US treasuries. However, the tides could quickly turn if the US experiences some weakness in the coming months. If the US consumer sneezes, the world economy could easily catch a cold, so to speak.

But even if this becomes a reality, another shift back in consensus expectations from "higher-for-longer" to "rate cuts are coming" could be perceived as a tailwind for stock markets in the short term. While continuously high-interest rates signal that the market can cope with current interest rate levels (beneficial for stock prices), even slight decreases in central bank interest rates are also considered supportive for the overall economy, keeping stock markets at current highs.

Although the situation is much different than in 2008, it's worth noting what happened with interest rates and stock prices back then. After the Greenspan Fed cut interest rates to 1% after the dot-com bubble, interest rates rose from mid-2004 onwards.

After that, long-term interest rates slowly increased, while the S&P 500 rose about 50% until 2007. When the Fed started to cut interest rates slightly, the S&P reached another high, while the 10-year yield began to fall along with the decrease in the Fed funds rate. However, it took more rate cuts as the economy slowed further to push the stock market lower.

That’s another reason I'm skeptical of reading too much into the current financial conditions indices, which suggest that financial conditions are as loose as they were when interest rates were zero. My view is that the development in stock market prices drives financial conditions, which is especially true if one assumes that higher stock prices can drive consumption higher due to a "felt" increase in wealth.

A pervasive and dangerous belief, from which I'm not exempt, is the magnitude in which things evolve. Sometimes, people can get ahead of themselves in their expectations of how fast things will happen. Therefore, I'd urge people to remain cautious about the belief that things like a collapse in stock prices or the economy are imminent because the data points to an increase in headwinds. Within markets, being too early but right has cost many a fortune and ruined some of them.

However, one should not be fooled by doomsayers who claim an economic collapse is imminent or by people in the "transitory inflation" camp who continue to claim victory. First of all, their argument was that inflation would have abated regardless of the level of interest rates, which is clearly not true. The disinflation was the direct result of the increase in interest rates and the drop in money supply growth, which are still at work due to the lag effect.

What should worry the proponents of higher for longer, in my opinion, is that this view has become widespread consensus over the course of this year. To paraphrase the legendary Felix Zulauf, the consensus is wrong mainly in one way or another. So, perhaps it's time to bury the "higher-for-longer" view.

It feels so different here now, like spiders under my skin

We're paralyzed but you and I are still alive

I'm not looking for a way out

Just a deeper meaning to the here and nowWhile She Sleeps – Sleeps Society

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for taking the time to read! If you enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to receive each post directly in your inbox. Additionally, sharing it on social media or giving the post a thumbs-up would be greatly appreciated!

All my posts and opinions are purely personal and do not represent the views of any individuals, institutions, or organizations I may be or have been affiliated with, whether professionally or personally. They do not constitute investment advice, and my perspective may change over time in response to evolving facts. It is strongly recommended to seek independent advice and conduct your own research before making investment decisions.

“Nevertheless, the recent ADP report emphasized that signs still point to a robust labor market, noting that annual pay increased by 5.1% this week.”

Which to your other point could mean those people with too little work experience to qualify for unemployment raise the average pay when they are let go much like what happened to average salaries at the beginning of the pandemic. I emphasize “could” as I’m a little skeptical the dismissal of new workers explains a lack of claims.