Self vs. Self

Despite a voluminous and often fervent literature on "income distribution," the cold fact is that most income is not distributed: It is earned.

Thomas Sowell

Covid, rising inflation, income inequality. In both the United States and Europe, calls for more government interventions and redistribution get louder and louder.

Interventionists from the left and right celebrate the Spanish government's market interventions to fight consumer price inflation, making headline inflation the lowest within the eurozone. However, proponents of such measures do not bother with the fact that similar actions have led to scarcity, like in Hungary.

Yet, the 2020s just amplified the trend that started after the Great Financial Crisis in 2008, as more and more people and politicians favor more interventionism and central economic planning.

On both sides of the Atlantic, governments ramped up fiscal spending. The EU issued joint debt at the height of the pandemic to finance various infrastructure and green projects through the Covid recovery fund.

The US handed out extensive checks of stimulus to the population during Covid. Now, Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act tries to incentivize businesses to relocate production from elsewhere into the United States by granting them government subsidies. Because of the brewing geopolitical tensions on the European continent and their consequences, many European businesses are considering shifting production facilities to the US. One should not be surprised that the EU is furious about it and wants to implement countermeasures to make companies stay.

The times of increasing globalization, which started in the 1980s and got another boost in 2001, when China joined the World Trade Organisation, are reversing. Liberal policies are replaced with protectionist policies. However, one should not forget that international free trade is only one side of the coin, as interventionism has been on the rise in the US and (Western) Europe.

Nevertheless, the hopes that more government spending and interventionism could spur economic growth turned out to be wrong once again. Especially a look at Europe makes this evident. After the GFC 2008 and the subsequent sovereign debt crisis, the ECB kept interest rates at or below zero to buy time for highly indebted governments. But it only incentivized governments to keep spending high while growth remained stagnant.

Interventionists want more social balance between societal groups. Their model is based on ancient times when people organized in small groups. In those times, the group redistributed the fruits of their labor among their members equally.

But it took the Industrial Revolution to spur the development of more wealth for the broad masses of society. Nowadays, these people enjoy a much better life than the elites of the 16th Century. It was the rise of liberalism, or free market capitalism, that made this possible.

Since Adam Smith published his Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of The Wealth of Nations, one of the main questions in economics is to distinguish what drives economic growth. Smith concluded that it was primarily an increase in the division of labor that led to a rise in productivity.

After all, economic growth means that an economy can produce more output with the same amount of inputs (land, labor & capital). If an entrepreneur finds a new production method to produce more quantities of a good A with an input Q, she can sell the product at a lower price but will generate more revenue due to an increasing market share.

Nowadays, people refer to a country's change in its Gross Domestic Product when they talk about economic growth, which is slightly different than the classical definition. GDP measures the value of all domestically produced goods and services and thus is often criticized as a measure of wealth because a rising GDP must not necessarily result in a wealthier population.

At this point, central bank and economic policy come into play. The argument for an active role of central banks and economic policies is the belief that they can reach a better outcome than the free market.

Central banks try to manage the economy through their interest rate policy. If it lowers interest rates, it wants to spur bank lending and nominal growth, while it raises interest rates if nominal growth and inflation are too high. At least, that is the theory behind it.

Since interest rates reached their post-World War 2 high in 1980, central banks lowered interest rates in every crisis to spur growth. Yet, they consistently failed to bring interest rates back to pre-crisis levels.

Many economists point to structural problems like regulations, taxes, bureaucracy, shrinking demographics, and increasing debt levels as why interest rates have been downtrend since 1980.

Certainly, rate cuts from the Fed, the Bank of Japan, the German Bundesbank, and later from the ECB did not lead to the growth that central bankers and politicians have hoped for, on the contrary. Nominal growth is also in decline since 1980.

The obvious question is whether lower nominal rates lead to higher economic growth. Economists Richard Werner and Kang-Soek Lee have studied the relationship between interest rates and nominal growth in their paper Reconsidering Monetary Policy: An Empirical Examination of the Relationship Between Interest Rates and Nominal GDP Growth in the US, UK, Germany, and Japan and concluded:

Examining the relationship between 3-month and 10-year benchmark rates and nominal GDP growth over half a century in four of the five largest economies we find that interest rates follow GDP growth and are consistently positively correlated with growth. If policy-makers really aimed at setting rates consistent with a recovery, they would need to raise them. We conclude that conventional monetary policy as operated by central banks for the past half-century is fundamentally flawed.

In theory, one would expect that interest rates and growth have a negative correlation and that lowering interest rates lead to rising growth while higher rates should dampen it.

Chart 3 shows the yearly change in nominal GDP and the 10y Treasury yield. One sees a positive correlation, meaning that interest rates follow nominal GDP, not vice versa, as the theory assumes.

Nominal yields of longer-term bonds reflect real growth and inflation expectations. Or, put differently, rising nominal growth due to monetary expansion raises inflation expectations, pushing nominal yields upwards.

Does this support Werner and Lee’s thesis that central banks need to raise interest rates instead of lowering them to create growth? I would argue that the hypothesis is partially correct. At this point, it is helpful to remember an effect Milton Friedman called the interest rate fallacy:

After the U.S. experience during the Great Depression, and after inflation and rising interest rates in the 1970s and disinflation and falling interest rates in the 1980s, I thought the fallacy of identifying tight money with high interest rates and easy money with low interest rates was dead. Apparently, old fallacies never die.

While Friedman’s argument seems counterintuitive initially if you look at it from an economist's perspective, it does not if you look at it from a banker’s perspective. Let us assume that a bank can either issue a loan to a business that plans to build another production facility or invest in financial assets.

If rates are low and the yield curve is flat, the markup the bank can earn from issuing the loan is also narrowing. The bank can buy financial assets for a slightly smaller yield, which is much less risky than handing out a loan to the real economy.

As a result, lower yields also lower the willingness for banks to issue real economic loans because the risk spread is too low. If interest rates rise, banks earn a higher risk spread from the debtor. Looking at the yearly change in loan growth and the Effective Fed Funds Rate, one can see that loan growth picks up when interest rates rise.

It is just logical that rising nominal growth and nominal yields go hand in hand, as rising interest rates increase the incentive for banks to lend, which further fuels nominal growth. However, at a certain point, when credit conditions get too tight due to high rates, the demand for lending drops. Of course, banks would love to lend money for 50 % interest, but the problem is that there is no demand at such a high rate.

Therefore, the relationship between real GDP and nominal yields is worth looking at. High nominal yields push down real economic growth at a certain point, which then drags down nominal interest rates. Since the 1960s, nominal interest rates between 4 - 6 % led to real growth in a 1 and 4 % range, where fluctuations can be traced back to different stages in the business cycle.

We can conclude that higher nominal growth and a following rise in nominal interest rates only reflect that market participants expect a surge in inflation and hence demand a higher compensation (higher yields) for bonds and that banks will raise their lending rates.

If one analyses real interest rates and real GDP, the correlation decreases to 7 %, which could reflect the troubles of defining economic growth as the change in GDP. Remember, banks expand lending when the central bank starts to raise interest rates from the lows.

But during that period, interest rates are still below the market equilibrium rate, leading to capital misallocations, which are positively reflected in GDP numbers. Take the housing bubble in the US as an example, where more homes were built than people demanded.

The critique that GDP is a lousy measure of wealth is not untrue. To quote Winston Churchill, it is the worst, except for all the others. The houses built increased GDP, as they caused a rise in production in certain aspects, but with no sustainable effect.

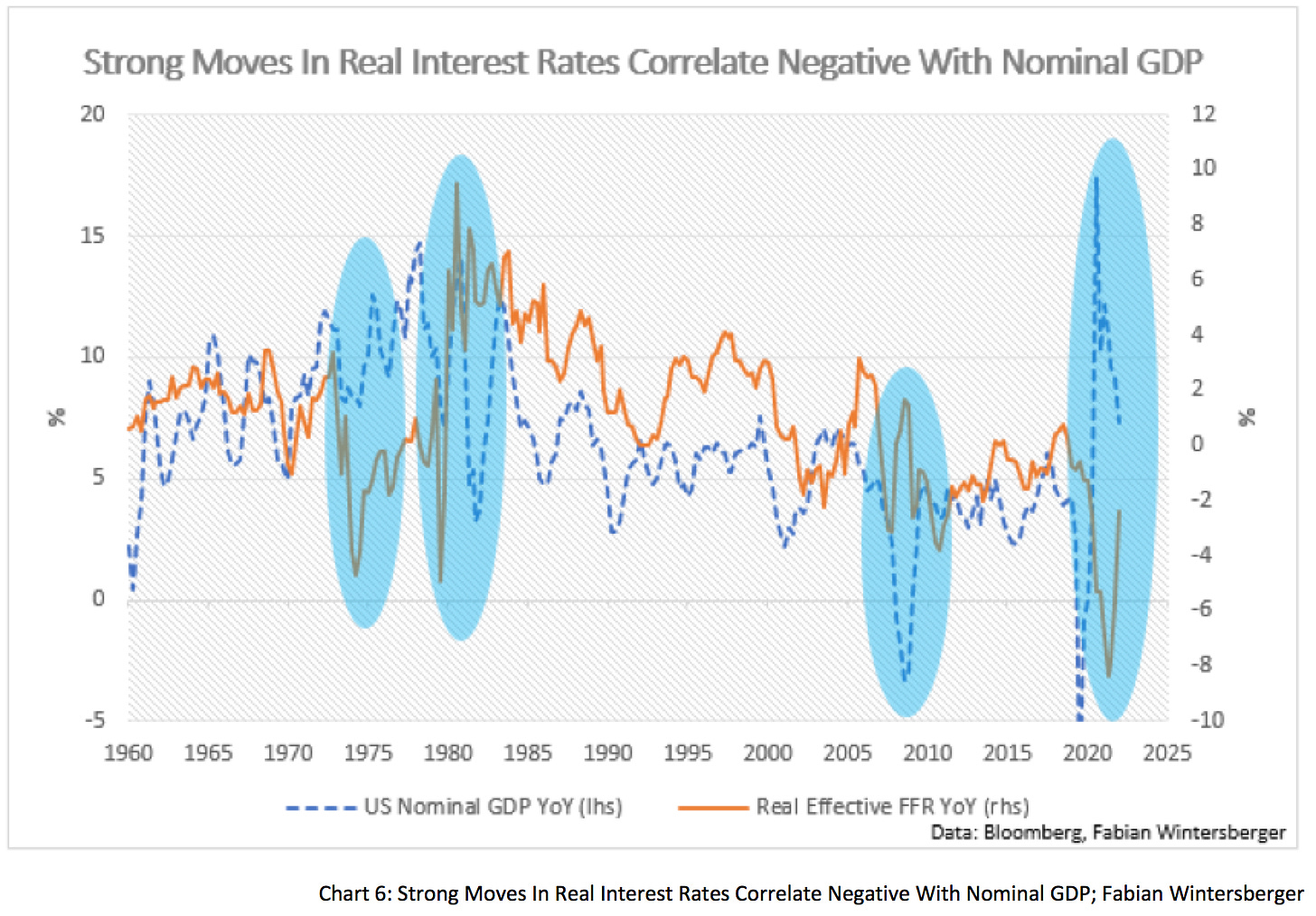

If one looks at real interest rates and nominal GDP, the effect is very close to what one would expect because of economic theory, especially when there are sharp moves in the real interest rate. Strong movements in real interest rates in the mid-70s, 1980, 2008, and 2021 correlated negatively with nominal GDP growth.

Another influence is that a rise in government investments tends to crowd out private investment and contributes to lower economic growth, as we have seen in Europe during the 2010s. The trend towards more regulation also means offsetting demographic change with increasing productivity growth will be more challenging. Some people argue that Chat GPT might be able to achieve that while the EU is already in discussions on how to regulate it.

Thus, it is not inexplicable why there is no imminent recession on the horizon, and we still see a slight, real economic expansion. Real economic lending growth spreads throughout the economy, simultaneously with people spending their high savings from the pandemic.

As soon as financial conditions get too tight and remain tight, loan demand will drop, and misallocations from the low-interest rate phase will become apparent. Then the economy will approach a landing, and you can be sure it will not be the soft landing central bankers hope for.

If I got no plan, Doesn’t mean that I get what I want for free

If I got no meaning, Would you force me to a place where I make sense?

‘Cause nothing lasts forever…How do I get home? Everything revolves around me

If I can’t find myself? It’s so completely fakePendulum feat. In Flames – Self vs. Self

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! If you like my writing, you can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox. Also, sharing it on social media or liking the position would be fantastic!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice)