Let It Go

In every culture, there are stories of wondrous encounters passed on over generations end then exist in various versions. We all know these stories as fairy tales.

The most well-known collection of fairy tales from the Arabic region probably is the Tales from The Thousands And One Nights, while most known fairy tales in the German-speaking area of Europe are those collected by the Grimm Brothers. In Scandinavia, Hans Christian Andersen is the most famous author of fairy tales, although Andersen actually wrote them, while the Grimm Brothers merely collected the widely spread folklore.

Nowadays, fairy tales are most popular among children, possibly because, with the rise of movies, dozens of them have been filmed in various versions, not only in Europe but only in the United States. Walt Disney’s first full-length animated feature film, Snow White And The Seven Dwarfs from 1937, is an adaptation of one of the fairy tales collected by the Grimm Brothers.

Many other animated Disney movies are versions of fairy tales from different countries, like Cinderella (in German: Aschenputtel), Pinocchio, Sleeping Beauty, Beauty And The Beast, Aladdin, Tangled, or The Princess And The Frog, which is loosely based on the Frog Prince.

The story of another great success of Walt Disney from the 2010s, Frozen, is also developed from another fairy tale: Hans Christian Andersen’s The Snow Queen. Although the movie is nearly ten years old, it is still extremely popular among children in infancy, especially girls. Until now, Frozen has earned a worldwide box office revenue of 1.28 billion dollars to become the highest-grossing animated film of all time.

Yet, Frozen is not a classical fairy tale. Usually, fairy tales are about a hero’s journey, while the main character of Frozen is the young Anna, the sister of the Snow Queen, Elsa. Since birth, Elsa possesses magical powers allowing her to control ice and snow, but one day, Elsa accidentally injures Anna with her magic, as her powers get bigger. As a result, her parents isolate her and close their castle gates to the public.

One day, Anna and Elsa’s parents get lost at sea, so, at age 21, Elsa is due to be the crowned queen. At first, she can control her magic, but after a dispute with Anna, all guests become witnesses of her powers. As she can still not handle them properly, the whole Kingdom of Arendelle gets covered by ice during her flight.

Elsa flees to the North Mountain, where she builds herself a gigantic castle out of ice. Meanwhile, her sister Anna has left the castle to look for her and to bring her back to Arendelle so that Elsa can end the Winter she caused with her magic. Like all fairy tales, the story has a happy ending, as the Snow Queen realizes the way to control her magical powers is through love. In the end, she can end the Winter, and Summer is returning to the Kingdom.

Interestingly, the most popular character of the movie is not its main character, Anna, but Elsa, the Snow Queen. She sings the well-known song Let It Go in the film and is the best-selling merchandise article of all characters in the movie. If you are the father of a daughter, as I am, you know it well: Every girl wants to be Elsa, not Anna.

Further, the song is also why the screenwriters turned the whole movie around during production and turned Elsa from the villain into Anna’s sister. While there are various theories all around the world wide web about what Elsa represents, the most obvious thing about her character is that, although she tried it for years, she could not repress her powers forever. Finally, they broke out of her and led to all unavoidable consequences.

If you think of fairy tales, one may also think of some projections of western central banks. Currently, the ECB and the Fed are assuming that Europe can avoid a recession while the US economy could do the same, or at worst, will only suffer a very mild recession.

Yet, not only do the ECB and the Fed think that that is the most likely scenario, market participants and a majority of economists agree with them. Larry Summers, a powerful critical voice regarding the Fed, said this week that a soft landing is more probable than it was a few months ago.

Especially the robust NFP data that was published last week supports that assumption. While consensus estimated an average increase of nonfarm payrolls by 189,000 dollars in January, the actual number beat it by a wide margin. Nonfarm payrolls rose 517,000 dollars in January and are now on their longest streak in history, where they continuously beat the consensus estimate.

US unemployment fell further, from 3.5 to 3.4 %, while economists expected a slight increase to 3.6 %. In December, there were 1.92 job offerings per unemployed person, which means that the labor market is still extremely tight, holding up wage pressures. Average hourly earnings rose by 4.4 % year-over-year, while the annualized number for January was 3.6 %.

However, it is worth looking a bit beneath the surface of the NFP headline number. As it turns out, the number of full-time jobs in the US economy has stagnated for a year now, while part-time jobs have risen. That means that the creation of lower-paid part-time jobs primarily causes the rise in nonfarm payrolls.

Further, the NFP data for January is always a bit noisy because of methodological changes that occur at the beginning of each year. Yet, monthly wage growth of 0.3 % hints that wages are not rising fast enough to create more inflationary pressures.

The US service sector PMI also surprisingly expanded recently, which suggests that the service sector is growing while the US manufacturing PMI contracted further. This is a potential sign that the worldwide economy is starting to cool off, and rising inventories of US retailers support that assumption.

As western economies are, for a considerable part, service-sector economies, the data speak against the thesis that the US economy is close to a severe downturn. Moreover, it seems that the US economy can still cope well with the latest increase in the Federal Funds rate.

Despite the compelling NFP numbers, let us remember that the labor market is a lagging indicator. An observation of prior recessions shows that the unemployment rate always reaches its low right before the downturn begins and then, during the recession, spikes. Therefore, one can argue that the labor market is no help in estimating whether the Federal Reserve can achieve the goal of a soft landing. Yet, concerning current labor market data, one can conclude that the Fed has no reason to end its restrictive monetary policy stand any time soon.

With European and US economic data surprising to the upside, one can argue that both central banks must stay on their restrictive course of monetary policy. And both central bank chairs, Jerome Powell and Christine Lagarde, have emphasized that.

Nevertheless, market participants are not buying the higher-for-longer narrative of the ECB and the Fed. Since last week’s FOMC meetings, market participants are still projecting interest rate cuts in the second half of the year. However, they now expect interest rates to rise slightly higher than anticipated a month ago.

In the case of the ECB, market participants did not change their expectations regarding the future path of Eurozone interest rates at all, even though Christine Lagarde tried to ensure markets at the ECB press conference over and over again that the ECB would stay on course to bring CPI back down to 2 %. Market participants expect Eurozone interest rates to peak around 3.5 % during the coming months and that the ECB will then follow the Fed and start to cut interest rates in the third quarter of 2023.

That means that market participants are not in agreement with either the Fed or the ECB about the future path of interest rates, even though they agree that it is probable that either both economies can avoid a recession this year or that Europe can avoid it, while the Fed can achieve its goal of a soft landing. However, as previously mentioned, market participants expect both central banks to start cutting interest rates again later this year.

Because of the expected path of interest rates, one can assume that the market expects a significant drop in CPI numbers down the road. In contrast, most economists only expect a gradual decrease. For January, economists estimate a month-over-month consumer price inflation rate of 0.5 %, translating into an annualized rate between 5 and 6 %. Although I want to add that the 3-month annualized consumer price inflation rate would still be 2 %, supporting the thesis of market participants. In Europe, 3-month annualized consumer price inflation is even -3.6 %.

Yet, the end of China’s zero-covid policies could be a spoilsport here. Through 2022, Chinese households accumulated cash reserves of 2.6 trillion dollars. Now, as life in China gets back to normal, those cash reserves could, similar to what happened in the west, flow back into consumption, possibly also influencing western consumer prices due to international trade. If that scenario occurs, I would argue that the market is currently underestimating the path of interest rates in the Eurozone and the US.

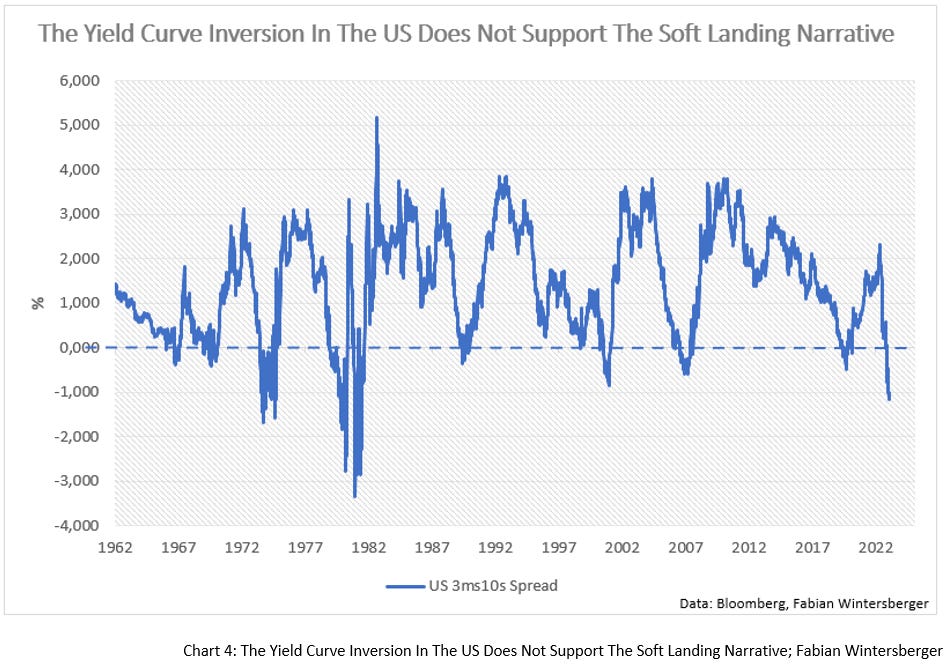

But even if we do not consider that scenario, another essential indicator that counterargues the Goldilocks or soft landing scenario that central banks and market participants consider as the most possible one: the inverted yield curves in the US and Germany. A negative spread of 3 months - 10-year yields correctly predicted all US recessions in the last sixty years, where the yield curve inverted two to six quarters before the recession started. The three months - 10-year spread inverted in October of last year, and therefore, it forecasts a recession to happen somewhere between April 2023 and April 2024. However, two Fed economists recently challenged the theory and argued that the indicator would not be valid this time.

Various theories try to explain why the yield curve inverts before a recession. According to the theory of Keynesian economists, such as Paul Krugman, the inversion happens because market participants expect the economy to fall into recession. Yet, a look at past data questions this theory because the inversion would be caused by longer-term interest rates falling faster than short-term interest rates, which are more influenced by the central bank’s prime rate.

Historical data shows that the yield curves invert because the opposite happens: the inversion is caused by short-term interest rates rising faster than long-term interest rates. That observation is in line with the Austrian theory of the business cycle.

In contrast to the Keynesian view, the Austrians argue that rising interest rates do not cause a recession but that it is the artificial loosening of monetary policy of the central bank before which makes a recession unavoidable. Artificially low-interest rates lead to a reallocation of resources, which causes an artificial boom in the sectors where the additional money is going while other, more profitable projects are not realized. The longer interest rates stay artificially low, the more economic imbalances they create.

When the central banks start normalizing interest rates again, those imbalances start to discharge at one point. It turns out that many investment decisions which were made during the boom were unprofitable. Therefore the recession is unavoidable and necessary to reestablish another reallocation of resources to a more sustainable equilibrium of the economy.

Within an economic regime with elevated prices, like the current one, central banks are forced to slam the breaks harder if they want to bring inflation back down to their target, and thus, short-term interest rates rise faster than long-term interest rates. Based on the Austrian business cycle theory, one can assume that the more the yield curve inverts, the more painful the recession will be.

That leads to the question of why Jerome Powell and other Fed officials are still projecting a soft landing as the most likely scenario. The answer to this question is much easier than you might think, and it has very little to do with the Fed’s econometric models.

It is not about the data on why the Fed is not forecasting a recession. In fact, it is not forecasting a recession because the officials know that their words significantly impact future market developments. Just imagine what would happen within financial markets if Jerome Powell announced that the US economy is on the brink of a very severe recession.

Looking back in history, one finds out that the Fed is always forecasting a soft landing. During a speech at America’s Community Bankers Meeting in December 2000, the then chair of the Federal Reserve, Alan Greenspan, said that economic risks in the US economy are broadly balanced. Just a few months later, the US economy fell into recession. However, that recession was relatively mild within the real economy because the dot-com mania in the stock market broadly caused it.

In February 2007, when the US housing market was already under severe pressure, Fed chair Ben Bernanke portrayed a ‘Goldilocks economy and that the US economy remains on track for a soft landing and a modest slowdown.

The statements of Greenspan and Bernanke are remarkably similar to the current Fed statements. Did neither Greenspan nor Bernanke know what was coming? The number of economists working at the Fed makes me doubt that. Instead, I would assume that the Fed is not forecasting a recession because it fears that the mere announcement would lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy and that the Fed wants to avoid that.

By which the circle closes, and we are back at Frozen. Like Elsa, the Snow Queen, the Fed can try to keep risks under the surface for as long as possible and to procrastinate them. But similar to what happens in Frozen, those imbalances cannot be suppressed forever and will discharge at some point.

Like the Snow Queen, the Fed needs to Let Go to be able to master these forces again. That allows the economy to rebalance and eliminate the economic imbalances induced by its monetary policy. In that case, the economy can return to a more sustainable growth path.

Let it go, let it go, can’t hold it back anymore,

Let it go, and I’ll rise with the break of dawn,

Here I stand, in the light of day,

let the sttorm rage on…Betraying the Martyrs - Let It Go

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! You can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox if you like what I write. Also, it would be fantastic if you shared it on social media or liked the post!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice)