While most people in Europe think of professional wrestling as something ridiculous which cannot be taken as a serious sport, it is widely popular in Japan and the United States. Thousands of fans visit the shows weekly to see the big stars fighting on stage. The most well-known promotions that organize the exhibitions are World Wrestling Entertainment, All Elite Wrestling, and the Japanese promotion New Japan Wrestling.

In contrast to Olympic amateur wrestling, professional wrestling is more a play than a sport. Storylines created by screenwriters surround the fights, and the battles are more-or-less scripted. The promoters choose the winner in advance.

Yet, for some athletes, their professional wrestling career is only the beginning of a much bigger career in entertainment if one thinks of the well-known Hulk Hogan or the best-paid Hollywood actor from 2019 and 2020, Dwayne The Rock Johnson. So far, the newer description of professional wrestling is very descriptive, as they call professional wrestling Sports Entertainment.

One of the biggest stars in professional wrestling these days is Cody Rhodes, who returned from AEW to the WWE last year, although he was one of the founders of WWE’s main competitor.

Still, in 2016 it seemed that Rhodes had the best days of his career behind him. After he joined WWE, the biggest wrestling promotion worldwide, he couldn’t establish himself among the top stars on the roster. As a result, he left WWE in May 2016.

After some engagements in independent leagues and appearances at New Japan Wrestling, some other wrestlers and Rhodes founded All Elite Wrestling with American investor Tony Khan.

The show, in which Rhodes appeared as The American Nightmare, became very popular and quickly became the second biggest promotion after WWE in the United States. While WWE focused more and more on storytelling, AEW concentrated on the fights, something many fans of professional wrestling cheered. More and more stars moved from other promotions to AEW.

Finally, on February 2022, it was announced that Rhodes would leave AEW and will rejoin WWE, AEW’s rival. At WWE’s flagship event, Wrestlemania, Rhodes had the first appearance of his second term at WWE. Quickly, he became one of the top crowdpleasers until an injury forced him to stay on the sidelines. Last week, Rhodes returned and won the yearly Royal Rumble Match, which means that Rhodes will be headlining Wrestlemania and fighting for the most precious title of the promotion.

Consequently, it closes the circle in Rhodes's career, from his uprising to the WWE, fasting a niching existence in independent leagues, to being a founding member of the US's second-largest wrestling promotion, back to the top promotion in the world, the WWE. The years when Rhodes was outside of recognition for most wrestling fans ended in 2022. Now, he is a top star in the wrestling world again.

But 2022 was not only the year Cody Rhodes returned to the highest ranks of professional wrestling. Another topic celebrated its comeback in discussions about financial markets and the economy. For years it has been under the surface, and some even proclaimed victory over it after central banks desperately tried to reignite it with extraordinary monetary policy measures. 2022 also marked the return of inflation, unleashed by massive fiscal spending and loose monetary policy during the pandemic years.

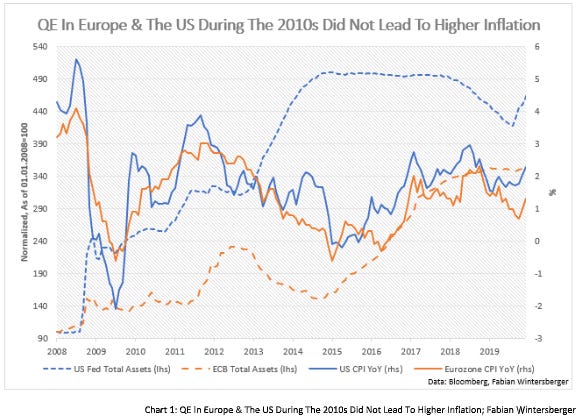

It was a return that was long overdue. After the Fed started to slash interest rates to zero and started massive bond-buying programs after the GFC in 2008, many critics warned that this might lead to extraordinarily high inflation.

In November 2010, former Fed chair Paul Volcker said that many investors are worried about potential inflation risks due to record-low interest rates and Quantitative Easing. At an event in Singapur, he noted that many people are concerned that the Fed will create so much money that it will lead to inflation down the road. I don’t think that the central bank cannot tame it, but it must deal with it.

Bond-buying programs, such as QE, were not wholly new in fighting the economic crisis. For example, the Fed bought bonds in the 1930s in its fight against the Great Depression, the Bank of Japan started QE in 2001, and the Bank of England followed the Fed soon after 2008.

Yet, critics of QE warned that it would lead to a massive increase of M1, which will spur inflation significantly if the banking system loans out the additional reserves to real economic actors.

Federal Reserve economists appeased the criticism and claimed that rising consumer price inflation results mainly from higher inflation expectations of consumers. Thus, they argued, QE only leads to rising consumer price inflation if the market sees it as a permanent monetary policy instead of something the central bank uses temporarily.

The European Central Bank also increased its balance sheet by doing QE during the 2010s. However, in none of those countries, QE led to a substantial increase in consumer prices.

There are various reasons for that why it was not the case. Let us take a look back at the GFC in 2008. In the end, it was not so much the struggling real estate market that caused the crisis to become a banking crisis but more because the banks had started to use mortgage-backed securities as collateral for interbank trades. Because the rating agencies gave those bonds the best credit rating, more and more, MBS were used as collateral in those trades.

As long as those bonds did not fluctuate very much in price, there was no problem. However, as the collateral suffers substantial losses, either the counterparty or the clearer of the trade will ask for additional collateral.

Simultaneously, commercial banks are forced to hold a certain amount of equity capital to keep their balance sheets sound. As a result, banks cannot grow their balance sheet indefinitely, even if customers demand more deposits.

During the crisis in the interbank market, as the pristine collateral MBS lost more and more of its value, banks were forced to deposit further collateral. At the same time, their equity capital started to erode. Banks had to sell other assets to fulfill regulatory requirements, which drove prices down in those markets. At some point, banks stopped accepting certain assets as collateral for daily interbank trading, which led to a collateral shortage.

The Fed’s Quantitative Easing program helped to strengthen the banks’ balance sheets, as it replaces assets on the balance sheet of commercial banks with bank reserves, similar to an asset swap when an investor swaps his holdings for cash. The goal to strengthen the banks’ balance sheet was achieved, but it did not lead to an expansion of bank loans.

Apparently, there is a main reason for that: it is not the case that banks loan out bank reserves when they make a loan. They simply create new currency units by expanding their balance sheets. Consequently, the amount of bank reserves defines how much the banks can lend to the real economy at maximum, but it does not automatically lead to higher loan growth.

That was what central banks hoped for when they induced their bond-buying programs. Yet, banks were reluctant to hand out credit because credit rates for real economic investment were also low due to the low-interest rate environment.

One may argue that the reason behind that is that banks have to take more risks in loaning money for real economic investments instead of refinancing reserves into financial markets. An investment loan binds capital for years, in which the economic environment can change drastically, leading to a write-off of the investment. Let us assume the creditor is considering a 5 % yield for the investment attractive. If the yield for his investment is only 2 %, however, he might think that the risk is too high compared to the lower yield he gets. As a result, an expansion of M1 does not necessarily lead to higher loan growth in the real economy.

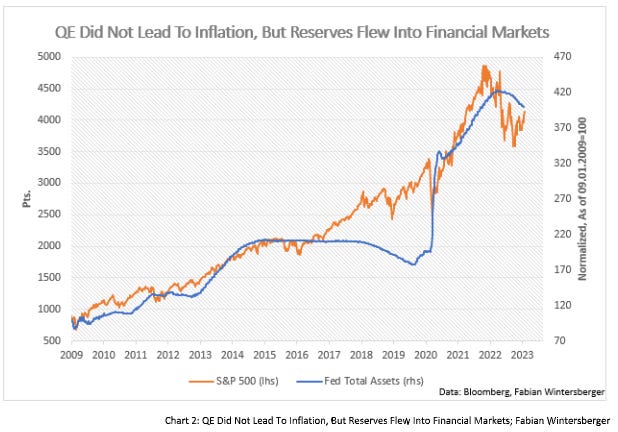

Still, commercial banks will reinvest their bank reserves by selling bonds to the central banks into financial markets, whether sovereign bonds, corporate bonds, or equities. In those markets, the additional bank reserves lead to increased demand, hence higher prices of financial assets, but not necessarily higher prices of consumer goods. So far, one can say that bank reserves are not money that can be spent in the real economy. Moreover, QE with commercial banks does not increase the quantity of money in the real economy, as the additional bank reserves replace the bonds on the commercial bank’s balance sheet.

If the seller of the bond that the central bank buys does not invest the reserves into the real economy but in financial markets, consumer price inflation remains dampened. Further, lower interest rates lead to a shift of investments away from the real economy.

Besides the fact that low-interest rates make investments in the real economy unattractive for banks, reinvestment of reserves into financial markets have an additional advantage, namely that they can be sold very quickly to buy other assets. As a result, the money stays within financial markets. It causes artificially elevated demand due to shrinking supply because central banks extract bonds from the market, and asset prices rise.

A brief observation of equity price developments post-08 seems to support the thesis that additional bank reserves mainly did lead to higher demand for stocks and bonds and drove prices up.

However, since the pandemic, inflation has celebrated a huge comeback, as central banks increased their bond purchases again and slashed interest rates (in the case of the Fed) to 0 %. The events since then show that low-interest rates and QE could lead to inflation, although some would deny that.

On the other hand, there are possible scenarios in which QE leads to rising consumer prices. If the Fed buys bonds in the market, it does not solely buy them from banks. It also buys them from investment funds, insurers, and other institutional investors. These institutions do not have the same regulation, which is why some additional reserves may indeed find their way into the real economy.

Let us assume the Federal Reserve buys bonds from an institutional investor. In that case, the investor gets additional dollars added to his bank account, while the bond goes from the investor’s to the Fed’s balance sheet. If the investor reinvests those dollars in financial markets, the money remains and causes asset prices to rise. However, he might also take the money to buy real estate, either by buying one off the market (which drives real estate prices) or financing a real estate project. If he buys it from someone else, the money flows to the seller, who can use it to buy tangible goods, leading to rising demand and higher prices.

As the investor is funding a new building because he is speculating on continuously rising home prices, he creates additional demand for commodities needed to build the house. He pays businesses and workers, who can also spend the money on consumption.

Thus, we can conclude that it depends on where the money flows to assess the impacts of Quantitative Easing on consumer price inflation. That explains why inflation during the 2010s once in a while spiked slightly above 2 %. Money flew into the real economy, pushing prices, but as that inflow was limited, the rate of change of consumer price inflation slowly decreased afterward.

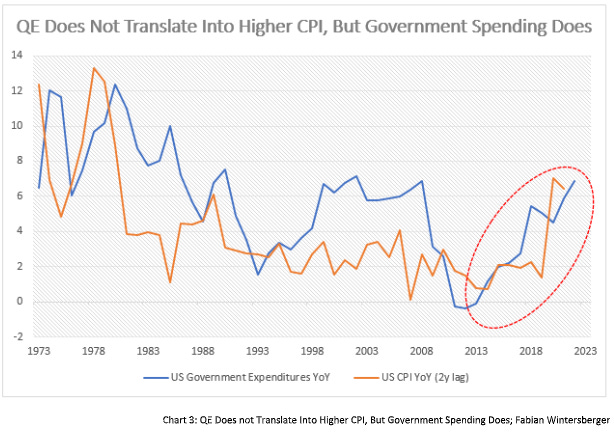

Now, let me discuss another actor who expectedly profited the most from QE and 0 % interest rates post-2008. The government could refinance cheaper via artificially suppressed interest rates, which created an incentive to take on higher debt.

If a similarly growing economy offsets the growing government expenditures, consumer prices will more-or-less stay the same and hardly rise. However, if we observe the post-2008 data, it indicates that higher government spending does not boost economic growth sustainably. That means that higher government spending will lead to higher consumer price inflation depending on their growth rate.

During the pandemic, governments all around the globe have tried to dampen the consequences of their covid-policies via higher government spending. While the US decided to hand out stimulus checks to its citizens, Europe primarily handed out money to businesses and implemented Kurzarbeit-schemes to keep people employed.

Keeping that in mind, it is easy to explain how the combination of QE, 0 % interest rates, and rising government expenditures fueled consumer price inflation. This phenomenon can be traced back to the late Obama years and the Trump era when Trump increased government spending to compensate for the losses in tax revenues due to his tax cuts.

Therefore, one can conclude that consumer prices will continue to rise if the money that central banks created through their bond-buying programs, but stayed within financial markets, finds its way into the real economy. Now, as the interest rates environment changes and yields rise, that might lead to a dangerous mixed situation.

The banks cannot use the reserves directly to fund real economic investments, but rising interest rates may increase their will to create additional loans. But as banks have been supplied with lots of reserves, they can expand their loan books and still fulfill equity capital requirements. More credit means more money creation, higher demand, and, as a result, higher consumer prices, especially if it leads to higher demand for goods where supply cannot grow in line with demand.

On the other hand, governments will face higher refinancing costs and thus have to borrow more money from financial markets to service the debt. Further, the current policy aims to finance the green transition via more government spending lets one conclude that not only will refinancing costs rise but total government debt in general.

Finally, businesses may increasingly think about real economic investment instead of, as from the 2010s on, borrowing money to buy back stock, which also supports the thesis of continuously higher consumer price inflation.

All the discussed points above could force central banks to stay more restrictive for longer to dampen the pressure of rising consumer prices than the market currently expects, which supports the thesis that stocks and bonds prices will have to fall and then probably lead to a demand shift, back from financial markets into the real economy.

Currently, asset prices are still high (and have risen recently) and hinder that because it keeps money within financial markets. However, if asset prices start to fall, the backflow of this money into the real economy will fuel inflation again, forcing central banks to tighten even more, a classical doom loop.

Hence, inflation could be like Cody Rhodes’ comeback. After a niche existence for years, inflation returned in 2022. The current consumer price disinflation is probably just an injury break before we see the real showdown between inflation and central banks next year. Unfortunately for all of us, it will not be at Wrestlemania.

You took it all away, I give it all away, can’t take my freedom

Here to change the game, a banner made of pain, I built my kingdomDownstait - Kingdom (Cody Rhodes Entrance Theme)

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! You can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox if you like what I write. Also, it would be fantastic if you shared it on social media or liked the post!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice)

that separation of funds in the financial markets and the real economy has been the missing link all along. It seems that the pandemic stimulus may have broken open that dam, holding the financial reserves back. I fear we will see more real economy spending, especially by governments, and therefore, more inflation in our future

Last para being nice example of market reflexivity thesis - let's see how it will play.