I do think there’s a path to bring down inflation while maintaining what I think all of us would regard is a strong labor market, and the evidence that I’m seeing suggests we are on that path…Are there risks? Of course. I don’t want to downplay the risks here, but I do think that’s possible.

We’re seeing those supply chain bottlenecks that boosted inflation, they’re beginning to resolve,” she said. “We had big shifts in the way people live and low interest rates, and housing prices rose a lot. Now, housing prices have essentially settled down.

US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen, 14.04.2023

We all know how fast things can change in financial markets. Out of the blue, problems that seemed solved can suddenly become important for investors again. Sometimes it does not have to be because of fundamentals; it is enough if many investors simultaneously become nervous.

Keynes was not wrong when he compared the price discovery in equity markets with a beauty contest. The majority can stay irrational for longer than you can remain solvent. From a fundamental perspective, however, there is little evidence that the latest troubles in the banking sector can cause a systemic banking crisis.

Former Fed trader Joseph Wang wrote on Monday:

The March panic was fundamentally a problem of a few poorly managed banks and not a crisis. Investors are no longer running to money funds and now appear comfortable again with the banking system. Overall bank lending activity was little changed in March and continues to grow in April. A number of regional banks also guided for continued loan growth in 2023, albeit at a slower pace than last year.

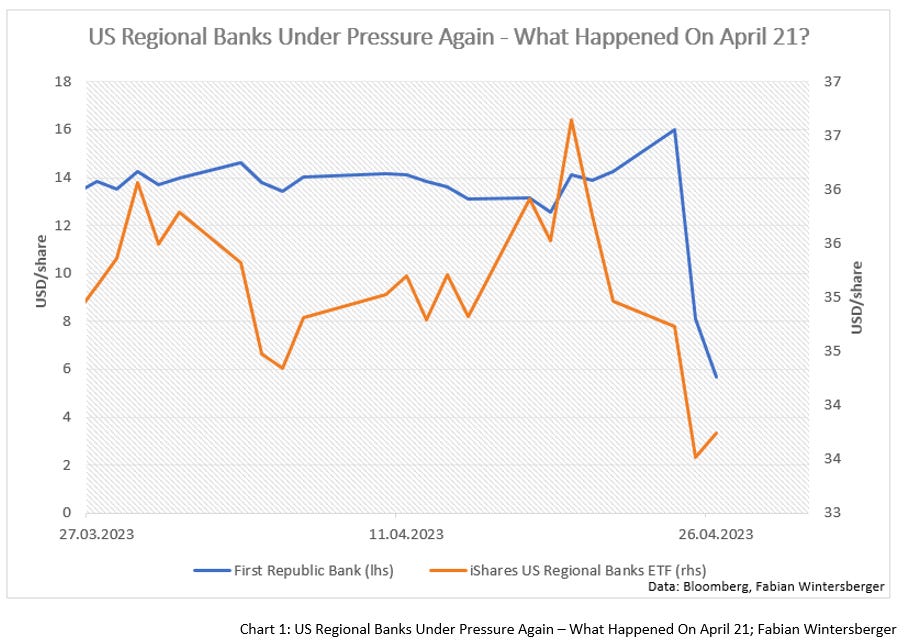

But in the following days, the situation changed, especially for First Republic Bank. Back in March, the bank was rescued via a joint action from the government and the big banks. On Tuesday, its share price dropped more than 60 %. On Monday, the bank announced that it lost deposits of about 100 billion US dollars during the first quarter.

Because of that, the bank faces a potential curb from borrowing from the Fed’s emergency lending facility, as Reuters reported. It seems as if the banks have decided to let First Republic fall. According to analyst Joe Consorti, a bankruptcy of First Republic would cost the banks 30 billion dollars, and providing liquidity for it means buying longer-term bonds worth 100 billion.

Yet, there is probably more than the announcement by First Republic Bank that caused the sell-off. Last Friday, the WSJ published a story that the Fed plans to close the loophole that allows small and midsized banks to mask their losses on securities they hold. Maybe this also helped to get investors nervous and let them sell their regional bank stocks.

Is it just another example of bad, incompetent management that First Republic Bank is likely also going down? In my opinion, which I stated in previous pieces as well, that regulation also played a role because it incentivized specific actions.

Analyst Richard Christopher Whalen is thinking of something similar. He believes that Jay Powell and Janet Yellen share a big pie of the responsibility for the current problems. On his website, The Institutional Risk Analyst, he criticizes that the latest recommendations by the Financial Stability Oversight Council do not even mention the impact of QE.

According to Whalen, the caused distortions in price discovery are one reason banks have trillions of dollars of low-yielding assets on their books. In his text, he calculates that the US financial markets would need to absorb trillions in securities losses to get clear of the cost of QE:

This process of loss recognition must occur at the same time that banks and leveraged investors are forced to reprice their funding costs. As the process of repricing of liabilities moves forward, more banks will likely fail.

One can assume that, at the moment, turbulence in the banking sector is subdued, but it can quickly become a problem further down the road. As we know from previous banking crises, sometimes it only needs the non-rational behavior of investors to draw attention to the risk that lurked beneath the surface. One should monitor the situation in the banking sector.

Now, let us talk about the latest Flash PMIs for the US and the Eurozone. For both regions, the PMI shows that economic activity is still expanding.

The eurozone composite PMI rose from 53.7 to 54.4 and reached an 11-month high. Service sector PMI reached a year high, 56.6. Yet, manufacturing PMI was disappointed with the most substantial decline since December, and the 45.5 points marked a 35-month low.

The labor market reflects the situation. While growth in manufacturing jobs was the slowest in 27 months, job growth in the service sector marked its most significant increase since July 2007(!). Combined, job growth reached an 11-month high.

While input prices continue to fall, output prices rose at the slowest pace in two years but still grew more than the long-term average. Prices in the service sector rose faster than at any point before the pandemic. However, slowing input purchases and falling inventories suggest that some businesses face slowing demand.

The German PMI showed that the economy improved across the board, mainly because of a sharp increase in the service sector PMI caused by a demand increase. The recovery of the German economy that started in Q1 continues. Lower input prices but steady demand means that businesses experience a rise in profit margins.

That underlines my thesis that the ECB will raise interest rates by 50bps next week, although many analysts still think it will only raise rates by 25bps. Isabel Schnabel told Politico last week:

People talk a lot about a potential peak in core inflation. I would not overemphasise the peak as such, because what really matters is that inflation is returning to our two percent target over the medium term… Concerning the May meeting, we made it very clear that the decision is going to be strictly data dependent…Data dependence means that 50 basis points are not off the table.

Interstingly, Schnabel also mentioned that she hopes for more progress in European integration on the fiscal side, a banking union, and a union of capital markets to bring some homogeneity in the heterogenous currency area.

In the United States, the economy also expanded. The service sector PMI reached a year-high, manufacturing PMI a half-year-high. Yet, prices increased at their fastest pace in 7 months, which points to a situation where inflation remains high and does not fall fast or, probably, regains momentum.

Price increases in the service sector businesses are driven because of higher capital costs (higher yields) and higher input prices. However, business confidence reached its second-highest level in a year, as companies hope for continuously strong demand.

Manufacturing PMI rose above 50, meaning the sector is slightly expanding. Additionally, businesses reported higher costs because higher input prices are only passed partially to consumers. Job growth in manufacturing was the highest since September 2022.

Not only do US PMIs suggest that consumer demand is still going strong, a chart by Goldman Sachs supports that. Real goods consumption remains well above its 2020 trend, and there is no sign that consumption will weaken in the coming months.

There is still no sign in the economic data that a recession is imminent. Moreover, the data points to two more Fed rate hikes at least. Nevertheless, market participants still expect rate cuts later this year, which might explain why stocks are still resilient. Most investors think that rate cuts mean a tailwind for stocks, although historically, significant losses for the stock market usually begin after the first rate cut.

But a strong economy is also bad for stock valuations and hence nothing for investors to be happy about because it means that interest rates will stay higher for longer. As a result, stock prices would need to adjust downwards in such a scenario.

So, how is this US recession? There’s a cloudy picture if one considers that PMIs show an economic expansion while leading indicators point to a recession.

Interstingly, the dot-com bubble and the GFC in 2008 collided with a rising US-budget deficit, a trend we can observe as well currently.

Especially since the GFC, a strong inverse correlation exists between the US yearly deficit/GDP and stock prices with a half-year lag (R2=19.8%). The latest weak tax revenue underlines that falling stock prices result in lower revenues for the US treasury.

A state can finance its expenditures in two ways: by collecting taxes or by borrowing capital markets. If tax revenues drop, the state must issue more bonds to keep spending constant. However, in contrast to the 2010s, it now has to pay interest, increasing the interest rate burden.

So, we can conclude that higher interest rates lead to falling asset prices, tax revenues, and inflation because of weakening economic activity, at least in theory. Usually, lower tax revenues should lead to more fiscal discipline, which is the catch.

The Biden Administration does not look like it plans to cut spending, and thus I think that consumer price inflation will stay high. Yet, rising government spending is not a problem if economic growth is more elevated and total debt/GDP is decreasing.

Currently, US debt/GDP is at levels similar to those after World War II. Back then, the Fed capped treasury bond yields, and because inflation was high, the US’s debt/GDP ratio fell from above 100 % to slightly above 20 % in 1980. Three strong inflationary waves during the years after the war cut debt/GDP down to 60 %.

There is a lot of discussion about whether current consumer price inflation is more similar to the post-WWII inflation or the 1970s inflation. Although there are similarities with both, like high debt/GDP ratios (WWII) or supply chain problems and the energy crisis (the 70s), the comparison of the US yearly budget deficit and CPI supports the thesis that current inflation is comparable to post-WWII inflation, as both spikes are fiscally driven.

In the 1970s, energy price shocks caused a rise in consumer price inflation, made possible through expansionary monetary policies since the 1960s. Otherwise, there might have been a brief inflationary panic, but mid-term only a change in relative prices instead of a rise in the general price level.

That is why Chart 4 shows an upward trend for consumer prices. Until the mid-50s, apart from three strong spikes, consumer price inflation remained stable. Russel Napier formulated the thesis that nations will use a similar method as after WWII to bring down current debt levels.

Napier thinks that government measures like loan guarantees (which are still in place in many European countries) keep money growth and consumer price inflation high while governments inflate their debt away via capped yields and lower their debt/GDP levels. According to Russel, we are at the beginning of increased financial repression. Institutional investors will be forced to buy government bonds at a negative real rate, leading to falling equity prices because investors need to sell other assets to buy those bonds.

We have not reached that point yet, but in recent weeks, I have noticed that more and more experts call for a higher inflation target. If I remember correctly, Mohamed El-Erian was among the first who said that central banks should increase the inflation target from 2 to 4 %. The reasoning is that otherwise, central banks might risk financial stability because financial institutions (and governments) might be unable to bear the interest rate burden at some point.

Central banks played down the possibility of that, and rightfully so, because if they abandoned the 2 % inflation target, it would cost them the rest of their remaining credibility. As Lagarde put it, one can discuss that after reaching the inflation target.

But what if central banks already decided to raise the inflation target behind closed doors? In that case, denying it could help countries to bring down debt levels because of continuously low long-term interest rates.

Currently, 10y Treasuries yield 3.45 %, and 10y Bunds yield 2.40% as market participants expect a recession, hence deflation. Hardly anybody expects higher consumer price inflation over the long term. However, it is not the case that recessions always coincided with inflation rates below 2 % and most of the time, interest rates remained above 3 %.

If government expenditures remain expansive, the central banks can make market participants believe they want to reach 2 %. In comparison, inflation stays around 4 %, which will help to bring down debt/GDP levels, and one does not have to force investors to buy government bonds.

However, if central banks would announce that they will raise their inflation target to 4 %, it would mean that market participants need to adjust their inflation expectations. As a result, longer-term bond yields would spike upwards. Maybe, central banks try to mask that to delay the point where financial repression must be implemented to support governments in bringing down their debt levels.

Who am I?

So many faces, dressed in rags for all to see

Here I am in the mask

The Jester that wants to be freeIn Flames - I, The Mask

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! If you like my writing, you can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox. Also, sharing it on social media or liking the position would be fantastic!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice)

2-4% inflation target is more common for EM countries. We probably have a new long term GDP growth trend in DM countries below 2% if we factor in changes in demographics and productivity. So I guess the 2-4% target would be more a short term thing?