If the misery of our poor be caused not by the laws of nature, but by our institutions, great is our sin – Charles Darwin

On July 3rd, 2008, Jean-Claude Trichet stood before the press to unveil the European Central Bank's interest rate verdict. Little did he know that this decision would ignite one of the most significant controversies in the ECB's history.

2008 was a period of profound uncertainty in the global financial markets. The subprime mortgage crisis in the United States had morphed into a full-blown international banking crisis. Given the interwoven nature of global financial markets, European financial institutions found themselves far from immune, and governments were grappling with containing the fallout. As the head of the ECB, Trichet found himself in a highly precarious position.

In late 2007, the inflation rate within the eurozone had begun to climb, soaring from 1.9 % to 3.9 % by July 2008, raising alarm bells. Trichet and his fellow policymakers faced a pivotal decision: Should they raise interest rates to combat inflation or lower them to stimulate economic growth?

To the surprise of many, Trichet and the ECB chose to take action by increasing interest rates by 25 basis points. During the press conference, he articulated that the decision was made to forestall the potential onset of widespread secondary effects:

HICP inflation rates have continued to rise significantly since the autumn of last year. They are expected to remain well above the level consistent with price stability for a more protracted period than previously thought.

The reaction to Trichet's decision was a mixed bag. While some applauded him for his unwavering stance against inflation, others criticized the rate hike as a misjudgment, considering the ongoing financial crisis. Stock markets teetered, and economic analysts engaged in heated debates regarding the potential consequences of this move. As James Surowiecki aptly noted in a 2011 commentary:

But the move was remarkably ill timed. The crisis was already under way, European economic growth had slowed to a crawl, and within a couple of months the global economy had collapsed, inflation had disappeared, and the ECB was forced to slash interest rates, in an attempt to avert economic disaster. The July rate hike was like kicking the economy when it was down.

In 2011, however, Trichet and the ECB found themselves under criticism once more. Surowiecki's article elaborates:

One might have thought that the ECB. would learn from the experience. No such luck. This year, Europe has been wrestling with high unemployment, slow growth, and a continuing debt crisis, with the economies of Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain (the so-called PIIGS) struggling to avoid default. Given the situation, Trichet could have decided to keep interest rates where they were, as both the Federal Reserve and the Bank of England have done. Instead, the ECB. raised interest rates in April and, once more, in July. Again, as if on cue, European economic growth stalled and the continent’s debt crisis deepened, which has created problems for markets around the world.

However, let's bear in mind that by arguing this way, we may cloud the understanding of cause and effect. Most of the issues revealed by rate hikes stem from the accumulation of economic misalignments during periods when interest rates were artificially suppressed.

In the context of 2011 and the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, it wasn't the act of raising interest rates that triggered the turmoil but rather the situation in which countries suddenly found themselves dealing with historically low-interest rates. Consider Italy, for instance, which had never encountered yields below 8 % before experiencing the turmoil caused by introducing the euro. One could argue that interest rates had been meager during the early 2000s, and this low-rate environment was a primary driver of the economic dynamics set in motion and ultimately exposed in 2011.

Now, in 2023, we find ourselves in a situation where the ECB governing council has just announced its decision on interest rate policy. Christine Lagarde, Trichet's successor at the ECB, faces formidable economic challenges. Several eurozone economies teeter on the brink of a sharp contraction, a result of prolonged inflation, the conflict in Ukraine, and brewing geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East.

Much like the situation in 2008, the ECB anticipates inflation will persist above the ECB's 2 % target for an extended period. In this discussion, we'll delve into the implications of the ECB's choice to maintain interest rates at 4.5 % (Main Refinancing Operations Announcement Rate), explore any immediate repercussions, and consider what lies ahead in 2024 and beyond.

Let's begin with the governing council's decision and delve into the details of Christine Lagarde's and Giannis Stournaras' press conference from last Thursday. Following ten consecutive rate hikes, the European Central Bank has pressed pause, opting to keep all three ECB key interest rates unchanged. In her opening statement, Lagarde emphasized that:

Our past interest rate increases continue to be transmitted forcefully into financial conditions. This is increasingly dampening demand and thereby helps to push down inflation.

We are determined to ensure that inflation returns to our 2 % medium-term target in a timely manner. Based on our current assessment, we consider that the key ECB interest rates are at levels that, maintained for a sufficiently long duration, will make a substantial contribution to this goal.

Over the past year, consumer price inflation has shown signs of moving in a positive direction, dropping from 10.6 % to 2.9 % year-over-year. This trend has coincided with the ECB's consistent interest rate hikes. As of September, short-term interest rates have finally entered restrictive territory. The most recent Consumer Price Index (CPI) reading pushed them to 1.6 %, marking the highest real interest rate in 16 years.

Lagarde rightly pointed out that the recent decline in consumer price inflation is primarily attributed to base effects, with energy and food prices experiencing substantial increases a year ago but becoming less predictable due to new geopolitical tensions, particularly in the Middle East. She also emphasized that long-term inflation expectations continue to hover around 2 %, indicating positive expected long-term yields.

When examining the most recent inflation report by Eurostat, it's evident that the recent drop in consumer price inflation was primarily driven by a significant decrease in energy prices on a yearly basis. When excluding energy, consumer prices in the eurozone rose by 4.9 % year-over-year. Notably, prices for processed food, alcohol, and tobacco remain exceptionally high at 8.4 %.

On a country-by-country basis, the Netherlands (-1 %) and Belgium (-1.7 %) stand out as outliers on the downside, while Croatia, Slovenia, and Slovakia show higher inflation rates. In Spain, year-over-year inflation has seen a resurgence, underscoring that government measures to curtail price increases may, paradoxically, prolong elevated prices. Predictably, calls for extending these measures to support households are growing louder, which could, in turn, contribute to sustained high price inflation. Remarkably, core inflation remains similar across all eurozone countries.

Critics may argue that inflation rates are manipulated to downplay "real" inflation, such as the recent adjustments in Germany's weighting of housing, water, electricity, gas, and other fuels from 25.2 % to 16.5 % without clear justification. Nevertheless, the overall trend strongly aligns with what observers of broad money supply growth anticipated for Q4 – that disinflation in consumer prices will intensify.

The ECB, following the Neo-Keynesian approach that dominates many central banks, primarily focuses on finding the ideal interest rate level to fulfill its "price stability" mandate, with less emphasis on the money supply. Although Isabel Schnabel recently acknowledged that changes in the money supply can impact inflation, like most economists, she does not consider it the primary driving force.

This perspective is grounded in the fact that despite the expansion of the money supply in the 2010s due to Quantitative Easing programs, yearly consumer price inflation averaged about 1.3 %. It's evident that the early fears of QE critics, who anticipated rampant inflation, did not materialize.

However, it would be shortsighted to conclude that money supply hardly matters for inflation. First, there's a common misunderstanding about inflation, where it's often defined as the rate of change in consumer prices. As a result, monetary expansion that doesn't affect consumer goods and services isn't considered. When money drives up prices in financial markets, it isn't reflected in the CPI.

Second, the mechanism of QE involves central banks buying bonds, increasing the balance of their counterparties' bank accounts. In essence, QE primarily impacts narrow money (M1) but doesn't necessarily lead to significant growth in the broad money supply, which has a more substantial influence on inflation.

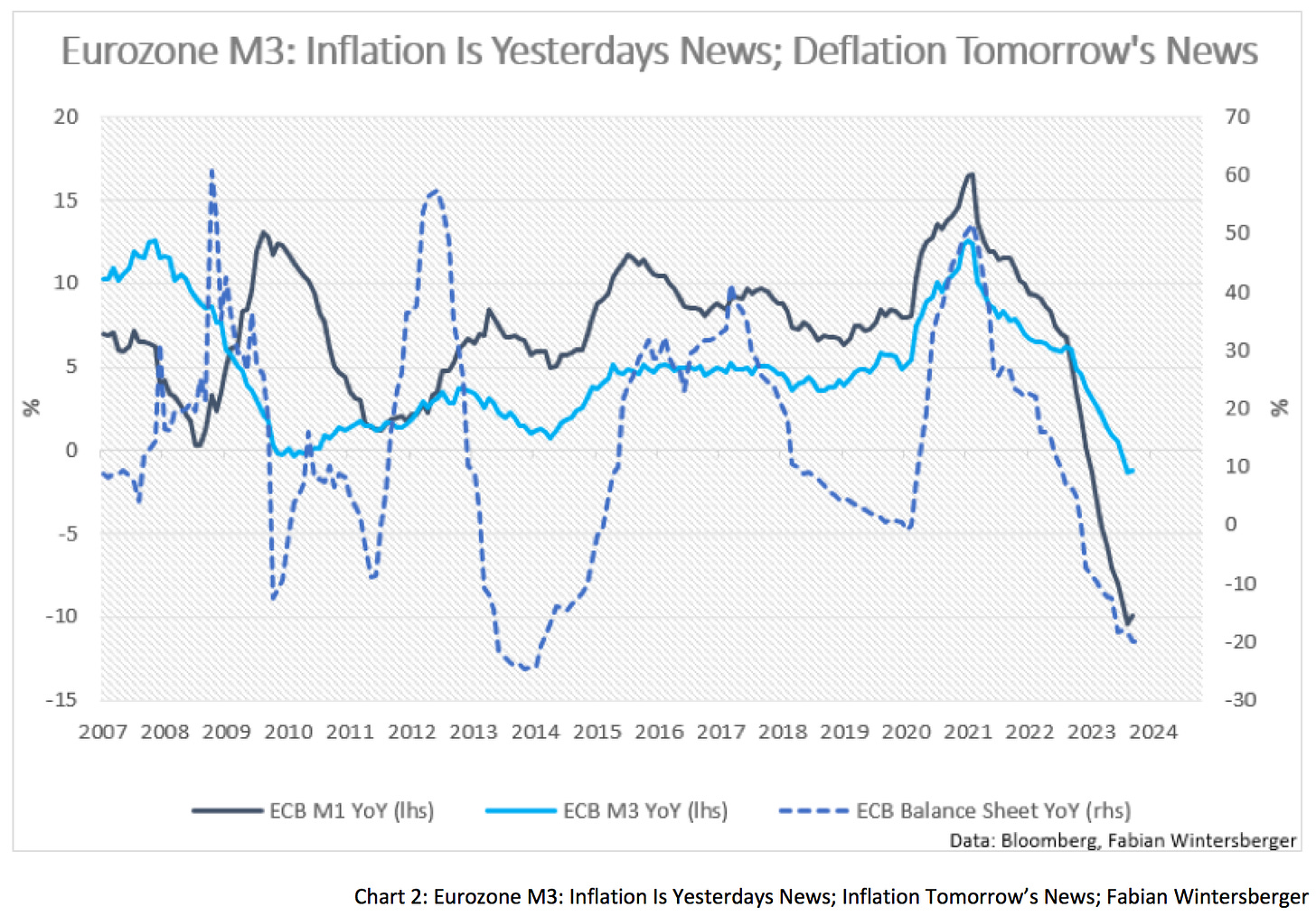

In summary, QE did not lead to high inflation during the 2010s because it remained contained in financial markets, driving up asset prices rather than significantly expanding the broad money supply. However, from 2020 onwards, the situation changed: initially, PEPP (akin to QE) expanded the broad money supply and fueled inflation. Now, as the broad money supply contracts due to the phasing out of bond purchases and a decline in bank credit growth, the indicators point toward price deflation in 2024.

Amid our heavily leveraged financial system, the contraction of the money supply serves as a warning sign for potential economic turbulence. While much attention has been focused on the United States, where the regional banking system showed signs of stress in March of this year, the European banking sector appears relatively stable. This is partly attributed to the support provided by the increase in interest rates last year, which bolstered banks' profitability.

However, the sustained increase in interest rates continues to impact loan demand. As interest rates climb, the cost of capital rises, which, in turn, diminishes the appetite for both investment and consumer credit. In a recent press conference, Christine Lagarde commented on this ongoing trend:

Higher borrowing rates, with the associated cuts in investment plans and house purchases, led to a further sharp drop in credit demand in the third quarter, as reported in our latest bank lending survey. Moreover, credit standards for loans to firms and households tightened further. Banks are becoming more concerned about the risks faced by their customers and are less willing to take on risks themselves.

This statement encapsulates the results of the ECB's latest bank lending survey for Q3. Notably, loan demand has diminished across various sectors, with housing experiencing the most significant impact. In Q3, the survey revealed that a net percentage of 45 % of banks reported a decline in housing loan demand.

The increase in interest rates has substantially curtailed loan demand, particularly for house purchases, despite not leading to a significant drop in home prices. Surprisingly, consumer loan demand has been the least affected, possibly due to government support for consumers in response to the energy crisis.

Now, let's turn our attention to the ECB's perspective on the economy, as articulated by Christine Lagarde during last week's press conference:

The euro area economy remains weak. Recent information suggests that manufacturing output has continued to fall. Subdued foreign demand and tighter financing conditions are increasingly weighing on investment and consumer spending. The services sector is also weakening further. The economy is likely to remain weak for the remainder of this year. But as inflation falls further, household real incomes recover and the demand for euro area exports picks up, the economy should strengthen over the coming years.

This week's economic growth numbers for Q3 have underscored the weaknesses in eurozone economies, which have fallen short of expectations. Overall, the eurozone economy contracted by 0.4 % (annualized) in Q3, with countries like Germany, Austria, Portugal, Ireland, Estonia, and Lithuania experiencing economic downturns.

The decline in economic activity is evident through various surveys, including the S&P Global PMIs, ZEW, and the Ifo Index, all indicating contraction. Companies are grappling with high energy costs and increasing labor expenses, particularly affecting the service sector. Higher refinancing costs from the rate hikes have also hurt investment and business activity.

Furthermore, the export sector is particularly affected by persistently weak demand from overseas, notably from China, Europe's largest trading partner. China is confronting its economic challenges, such as a real estate bubble, high youth unemployment, and subdued consumption. It's essential to understand that falling inflation is a consequence of a weak economy, not a sign of strength.

However, it would be inaccurate to attribute the eurozone's weak economic performance solely to the ECB's rate hikes. As mentioned earlier, interest rate increases primarily reveal the excesses and misallocations that were facilitated during the era of artificially low interest rates. In a sense, Christine Lagarde is dealing with the consequences of decisions made during Mario Draghi's tenure at the ECB, as well as her own.

Zero percent interest rates have prevented businesses from exiting the market, thereby disrupting the normal functioning of market forces. Under typical interest rate conditions, struggling businesses would go bankrupt, releasing resources that more profitable firms could use to increase their productive capacity. Although the exact figures may vary, it's reasonable to assume that approximately 10 % of companies could be categorized as "zombie" businesses.

With interest rates significantly higher than the lows, some of these zombie companies, which managed to stay afloat thanks to low interest rates, are now beginning to face financial challenges. This particularly affects small and medium-sized enterprises, especially those needing to refinance short-term debt soon. According to Eurostat,

the number of business bankruptcies were up by 8.4 % [compared to the previous quarter] and thus reached the highest level since the start of the data collection in 2015.

Despite the economic turbulence and gloomy outlook, one sector of the economy stands out: the labor market. Government policies subsidizing employment during the pandemic (Kurzarbeit) played a pivotal role in keeping unemployment at bay. In some countries, these schemes have become permanent fixtures, contributing to record-low unemployment rates across the eurozone.

Christine Lagarde reiterated the importance of government support measures in mitigating the impact of the energy crisis and emphasized the need for structural reforms. Furthermore, she suggested that Next Generation EU could play a role in alleviating price pressures:

As the energy crisis fades, governments should continue to roll back the related support measures… Structural reforms and investments to enhance the euro area’s supply capacity – which would be supported by the full implementation of the Next Generation EU programme – can help reduce price pressures in the medium term, while supporting the green and digital transitions.

While government debt-to-GDP ratios have decreased since the pandemic, thanks to high nominal growth and inflation, the energy crisis of the previous year has triggered increased government expenditures. This, in turn, will lead to higher interest rate expenses in the years to come. For instance, Germany anticipates a tenfold rise in interest rate expenses next year compared to 2021.

I've also mentioned the growing calls in Spain to extend inflation support measures, which directly contradict the ECB's stance. Given historical patterns, it's a bold assumption to expect eurozone governments to curtail their spending, which could result in further increases in interest rate expenditures over time.

Considering the eurozone's ambitions to transition into a green economy, there is ongoing concern that the assumptions regarding the potential outcomes of this top-down transition are overly optimistic. This could ultimately lead to higher future inflation due to capital misallocation and monetary expansion.

So, what does this mean for the eurozone economy and the ECB in the future? As I've previously mentioned, I anticipate that inflation is now a thing of the past, and a return to deflation next year is the most likely scenario, given the contraction of the money supply. Despite some expectations of relief in the upcoming months, my hunch is that the economic downturn in the eurozone will intensify in the near future, aligning with the decline in broad money supply. In conclusion, the ECB has finished raising interest rates.

Globally, stocks and bonds experienced a robust rally this week, but I maintain skepticism about the durability of this recovery. The eurozone government bond market, in particular, may encounter challenges down the road. European stocks remain under pressure and seem more likely to be sold rather than bought, especially since the policies of European governments are not making a compelling investment case.

Up to this point, the rise in long-term bond yields has been primarily driven by US interest rates. If the economic downturn deepens in the eurozone, debt-to-GDP ratios will likely rise substantially because I expect governments will combat the downturn with additional spending. However, the ECB has not even discussed the end of its Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program, although it has scaled back its Asset Purchase Program. Bloomberg's Marcus Ashworth recently argued that the ECB should not rush to reduce its balance sheet.

His point is that a rapid reduction of the balance sheet could trigger economic turmoil in the periphery, and I agree with his assessment. However, not reducing the balance sheet could backfire in the event of an economic downturn, necessitating an expansionary approach.

Currently, long-term inflation expectations are anchored at 2 %, but a gradual reduction of the balance sheet may lead to an increase in inflationary pressures and higher interest rate volatility. Conversely, accelerating QT could put pressure on banks, which hold a significant portion of government bonds and value them at par since they plan to hold them until maturity.

On a marked-to-market basis, some banks might already have negative equity, which could lead to turbulence in the banking sector if they are forced to sell these bonds. This is something the ECB would likely want to avoid.

It's challenging to envision a scenario where the ECB maintains a more restrictive stance than the Fed. The last time the market assumed that earlier this year, it faced a harsh awakening, leading to a selloff in the euro. Thus, I still anticipate a weakening of the EUR/USD exchange rate down the road for two primary reasons.

First, the ECB will never be able to outdo the Fed due to the dollar's global dominance. Secondly, as Europe relies on energy imports, it will require dollars to fuel its economies. Therefore, a weaker euro will compel the ECB to inflate the euro, as they will need to print euros to acquire dollars for purchasing energy and averting another sovereign debt crisis.

Currently, Japan's experience shows that selling US treasuries to stabilize the domestic currency may not have a long-lasting effect either. The ECB finds itself in a complex situation, and EU politicians are seemingly unwilling to confront the reality, perhaps not until the situation deteriorates further. However, there's still time to address these challenges…

So you take me, and you break me

And you see I’m falling apart,

Complicate me, and forsake me,

You push me out so farTrust Company – Falling Apart

I wish you a wonderful weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for taking the time to read! If you enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to receive each post directly in your inbox. Additionally, sharing it on social media or giving the post a thumbs-up would be greatly appreciated!

(Please note that all posts reflect my personal opinions and do not represent the views of any individuals, institutions, or organizations I may or may not be professionally or personally affiliated with. They do not constitute investment advice, and my perspective may change in response to evolving facts.)

I fear you are far too optimistic with respect to how EU politicians will respond. the first thing we know is they will never be proactive, rather, when the problems you highlight manifest themselves more fully, they will do something else. I suspect that the ECB balance sheet will have much further to grow if economic activity there declines as you imply it might. and I think you are right, things are going to slow further.