Duality

The four most dangerous words in investing are: 'this time it's different’

Sir John Marks Templeton Sr.

This week has been Central Bank Week on financial markets, with interest rate decisions from the Reserve Bank of Australia, the US Fed, and the European Central Bank.

But before, let us briefly touch on the first press conference of Kazuo Ueda, the new chair of the Bank of Japan, where he reinforced the BoJ’s commitment to easy monetary policy and yield curve control. However, the initial drop of the yen against the dollar reversed this week, with USD/JPY now only slightly higher at 134.72 (+0.68 %).

On Tuesday, the Reserve Bank of Australia started the week with a surprise and raised interest rates by 25 basis points, while most economists had expected the RBA to keep interest rates unchanged.

In contrast to the RBA’s decision, market participants expected a rate hike from the US Federal Reserve. And, as expected, the Fed raised the Federal Funds Rate by 25 bps to 5 - 5.25 %.

In the official statement, the FOMC changed two main points. On the one hand, tighter credit conditions are already weighing on economic activity (in the prior statement, it said that they are ‘likely to result’ in tighter credit conditions). On the other hand, the FOMC removed the part where they referred to future increases in the target range, which immediately fueled speculation that this had been the Fed’s final rate hike.

However, Jerome Powell did not want to confirm that fully and pointed out that the Fed would use future incoming economic data as the foundation for future interest rate decisions.

As I watched the press conference live, I did not get the impression that market participants should rule out another increase in the Federal Funds Rate at the next meeting. However, market participants seem to be sure and assume a probability of almost 100 % that the FOMC will not raise interest rates in June.

Assumingly, market participants expect that future economic data will show that interest rates are already restrictive enough to slow down economic activity.

Time will tell if market expectations are correct. Yet, in my opinion, current economic data does not hint that economic activity is slowing down as much as the Fed wants. If I understood Powell correctly, he is currently not in the camp of Fed governors who favor a pause in June.

For example, he repeatedly stated that there are still signs of excessive demand. However, he also acknowledged that credit conditions are tightening slightly more substantially than usual, referring to the change in the FOMC statement.

Additionally, Powell pointed out that the labor market is still tight, which the robust ADP National Employment Report on the same day supported. Private employment increased by 296,000, beating the estimated 150,000 by a wide margin, while wages rose 6.7 % compared to the previous year. We will see if Friday’s Nonfarm Payrolls confirm the ADP numbers.

Regarding wages, Powell argued that current wage growth is still inconsistent with 2 % inflation. However, he correctly pointed out that wage growth is not an initial driver of price increases but rather a result of it. He also correctly noted that this is usually when economic expansion ends. As workers can enforce higher wages, business margins decrease, and workers get a higher share of business profits.

Several journalists asked Powell about future rate cuts, as markets are pricing such a scenario. However, Powell was very clear and assured that the Fed plans to keep interest rates higher for longer. However, history does not support that, especially in an environment of high inflation, where the Federal Reserve historically cuts rates one month after the peak. When inflation is low, the Fed, on average, could keep rates at the peak for 4 to 5 months.

Maybe Powell is correct in his thesis that this cycle is different, and the labor market does not weaken too much because of the rate hikes. Like prior Fed chairs, he also tries to sell the soft-landing narrative to markets, saying there are higher chances the US economy can avoid a recession than experiencing one.

Whether he believes in it or not, market participants disagree and still think that the Fed will have to pivot after the summer. They expect the fastest interest rate hiking cycle in 40 years will be replaced by the most rapid rate-cutting cycle since 1980. Hence, they do not think that it is different this time.

One of the most apparent arguments supporting this thesis is that the United States, like all other highly indebted countries, faces a rapid increase in interest rate payments if rates stay higher for longer.

For the most part, the United States government financed itself by issuing short-term debt, which it now has to refinance at a higher rate. Positive real yields and tax revenues decline because of a slowing economy are a dangerous mix, as the government needs to increase borrowing if it wants to keep expenditures stable. Usually, nations solve this by accepting higher inflation rates (and higher nominal growth) for longer to lower the debt/GDP ratio.

Yet, looking at the US real economy does not support the thesis that the economy will slow rapidly. As the WSJ reported, US construction spending has reached a record high this year and helped to keep US unemployment at a record low:

Construction companies with jobs ranging from airport overhauls to bathroom renovations say they have enough work booked to maintain payrolls—for years in some cases.

Additionally, the number of businesses that beat earnings expectations in the first quarter was the highest in over a year. However, this is probably because many companies intentionally understated the case to get upside surprises.

Powell also mentioned the recent fall in loan growth, primarily caused by the Fed’s rate hikes but partially because of higher lending in 2022 in anticipation of rising borrowing costs. Many junk-rated did this in 2021 and issued bonds to lock in low-interest rates, of which a big junk needs to be refinanced between 2025 and 2030.

All this delays the impact of the Fed’s interest rate hikes on the real economy. As the latest S&P Global PMI shows, the US economy continues to expand in services and manufacturing. The latest ISM data supports the thesis that the US manufacturing sector is growing again.

This supports the thesis that the massive amount of liquidity injections (fiscal and monetary) from the previous years is still spreading through the economy and keeps it going. However, in the following months, we will see if this is correct because unemployment usually, on average, starts to rise 14 months after the first interest rate hike.

Summed up, current real economic indicators do not support a Fed pivot but support higher for longer interest rates. Yet, the real economy's resilience can become a problem if high-interest rates lead to turmoil in the financial markets.

On Monday, the turbulences around First Republic Bank ended. The FDIC seized the bank, and JP Morgan agreed to acquire it, although JP Morgan was already a too-big-to-fail bank before the acquisition. However, the downturn of regional banks stocks did not stop; the SPDR S&P Regional Banking ETF fell 10 % until Wednesday evening.

Therefore, probably Jerome Powell's statement on Wednesday that the US banking system is not in danger is incorrect. Banking expert Christopher Whalen is expecting more bank failures. Overall, his judgment about the US banking sector is devastating:

If you include the loan portfolio of US banks in the capital calculation, then most US banks today are insolvent on a fair value, mark-to-market basis because of the FOMC’s actions.

Yet, long-duration bonds are not the only problem for the banks. The inversion of the yield curve is another drag on lending, as the classical business model of borrowing short-term and lending long-term. This is just another result of the interventionist monetary policy that was kept in place since 2008 and distorted the price discovery of interest rates and caused capital misallocations.

Hence, one should monitor further developments in the US banking sector, although one should also have an eye on the European banking sector.

Bloomberg titled in February: European Banks Are Profiting Like It’s 2007. How Long Can It Last? Then and now, the ECB has raised interest rates steadily, which led to growing bank profits. This week, the ECB published its bank lending survey, which shows that the loan demand from businesses and households strongly decreased in the first quarter. The falling demand for corporate loans in the first quarter was the highest since 2009.

However, most surveyed banks said they expect rising profit margins because of rising interest rates, as deposit rates are still low and have only increased moderately. While US money supply M2 is already negative year-over-year, Eurozone M2 year-over-year is still positive because the ECB started its monetary tightening later than the Fed.

Meanwhile, the IMF estimated that European house prices are 15-20 % overvalued. Simultaneously, according to the ECB, 25 % of all house purchases in the Eurozone are financed at a variable rate. Falling home prices and high-interest rates could become a problem for the banks, depending on how many borrowers cannot repay the loan and have to default.

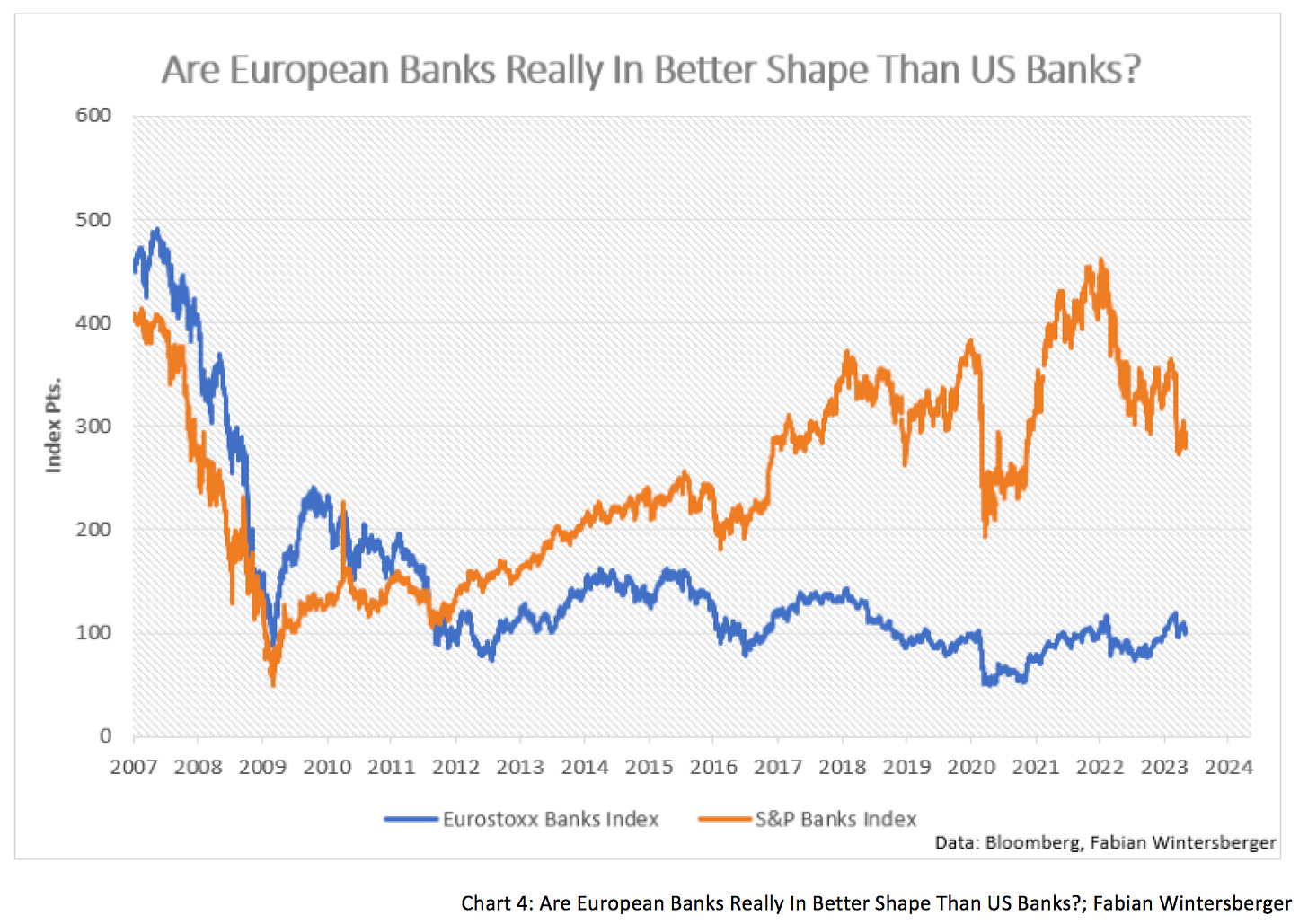

In contrast to the US banks, European banks never recovered from the Great Financial Crisis because the ECB never raised interest rates, and narrowing spreads dampened the banking sector's profitability.

Now, because of the inverted yield curve, interest rates on the short end are higher than on the long end. Hence, European banks are in a similar situation as banks in the US and might not be able to raise deposit rates very much.

Even though banking supervisors arguably did a better job in Europe than in the US, and the EU implemented a range of liquidity and capital regulations, one should not become deluded that the massive losses in the bond market since 2022 are no problem for the European banks. Just as in the United States, it could be that some European banks also have badly mismanaged their interest rate risks.

Nevertheless, European banks do not face an imminent similar scenario to US regional banks. As Reuters reported, according to a calculation by Legal and General Investment Management, theoretically, European banks can lose 38 % of their deposits before the losses of their hold-to-maturity assets become a problem.

Another aspect that supports European banks is that many countries still have credit guarantees in place, which means that the government will step in if a borrower cannot repay his loan. In my opinion, this is something that market participants pay too little attention to. As a result, European government bond spreads are still at low levels, despite the ECB’s ongoing balance sheet runoff.

Yet, because core inflation in the Eurozone is still stubbornly high, the ECB might be forced to continue with more interest rate hikes, which could drive government bond prices further down. As a result, rising mark-to-market deficits of European banks’ bond portfolios could become a problem at some point in the future. Simultaneously, higher interest rates also result in a sharp increase in refinancing costs for Eurozone countries.

Besides the ECB, European banks bought a significant portion of European government bonds, sometimes actively influenced by European governments. In a paper published in 2016, Ongena et al. analyzed data from 60 commercial banks within the Eurozone. They showed that domestic commercial banks expanded their purchases whenever it was difficult for them to refinance at low rates.

Since the ECB was forced to raise interest rates and shrink its balance sheet because of extraordinarily high consumer price inflation, banks have become the largest buyers of government bonds, as Reuters reported. The article also reveals which bonds they prefer:

Funding officials said bank treasuries usually buy bonds that mature in up to 10 years, but such is demand that they have become the leading investors in much longer-dated debt sales.

That is astonishing because it is not sure whether European consumer price inflation will drop as much as in the United States in the coming months. It should not be ruled out that European consumer price inflation bottoms at a higher level than in the US because of the expansionary fiscal policies of European governments (which are in place to dampen the inflation burden for Europeans).

Realistically, one also has to assume that in the case of a crisis, the ECB (and the Fed) will sacrifice their fight against inflation to ensure financial stability. This should cause a rise in inflation expectations and, thus, higher interest rates for long-duration bonds, not to mention the current discussions on whether central banks should raise their inflation target, which would have similar effects.

For this reason, investors should be aware that there is a possibility that potential risks harbored underneath the surface in the European banking sector could also suddenly materialize in case of a crisis. If they arise, one can take it for granted that governments will step in again to bail out the banking sector. Then it is not farfetched to assume that European government debt levels get in the focus of market participants again.

It is hard to forecast if or when this could happen or if it ever happens. However, if one thinks back to the Great Financial Crisis and how it unfolded, one realizes this could take a very long time. Back then, European politicians and central bankers always claimed that the problems were limited to the US banking sector.

Finally, when European banks got into trouble, European governments had to implement bigger and bigger rescue packages to fight the spreading panic. However, the excessive fiscal spending partially laid the foundation for Europe’s subsequent sovereign debt crisis.

As we all know, history does not repeat. But it often rhymes.

I push my fingers into my eyes,

it’s the only thing that slowly stops the ache

But it’s made of all the things I have to take

Jesus, it never ends, it works it’s way inside, if the pain goes on...Slipknot - Duality

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! If you like my writing, you can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox. Also, sharing it on social media or liking the position would be fantastic!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity and are no investment advice)

I heard it the first time from Andreas Steno and I really like his term “artificial steep yield curve”. He means that even when the yield curve is highly inverted, banks can create their own “artificially steep yield curve”, by keeping deposit rates close to zero and lending longer term.

I think that European banks might not have the same deposit flight issues that American banks face, as in the US you can just download an app called TreasuryDirect and buy US treasuries very easily. I’m not aware European depositors have the same option. I also think the avg European depositor is less aware of the money market option compared to a US depositor. Hence, European banks are in a luckier situation vs US banks. Also the recent bank test was showing that a 200bp increase in rates leads to a decrease of capital only of about 5% on average (200 banks were tested)