The government should pay people to dig holes in the ground and then fill them up. - John Maynard Keynes

By 1989, the East German economy was in dire straits, characterized by chronic shortages of goods and services, rising unemployment, and a lack of innovation. The centrally planned economy struggled to meet the basic needs of its citizens, leading to growing frustration and disillusionment with the ruling Socialist Unity Party. Many East Germans were becoming increasingly aware of the better living standards and freedoms enjoyed by their counterparts in West Germany, fueling the desire for reform. The stark contrast between the economic conditions in East and West Germany became a rallying point for demonstrators, who began demanding greater political freedom, economic reform, and recognition of their rights.

The Leipzig demonstrations began peacefully, with citizens gathering weekly at St. Nicholas Church, which soon became a symbol of resistance. As the protests gained momentum, the government attempted to suppress dissent, but these efforts only strengthened public resolve.

A pivotal moment occurred on October 9, 1989, when around 70,000 people took to the streets of Leipzig despite widespread fears of a violent crackdown. This show of solidarity not only underscored East Germans' determination to seek change but also exposed the vulnerabilities of the GDR regime, which was struggling to maintain control amidst growing discontent. The mass mobilization reflected broader demands for economic reform, political autonomy, and closer ties with the West.

These events in Leipzig were part of a larger wave of change sweeping across Eastern Europe, where economic crises and calls for reform sparked similar movements. The economic decline of the Soviet Union under Mikhail Gorbachev’s policies of perestroika and glasnost had a ripple effect on its satellite states, inspiring East Germans to demand greater rights and freedoms.

Ultimately, the Leipzig demonstrations were instrumental in the movement toward reunification. The persistent calls for reform and the refusal to stay silent in the face of oppression led to the collapse of the GDR by the end of 1989. The fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989, directly resulted from the momentum generated by these protests.

Today, Germany and many countries within the eurozone are again facing significant economic challenges. Just as Gorbachev tried to reform the Eastern bloc from within and guide it toward prosperity, European policymakers are now working to implement strategies aimed at reviving struggling eurozone economies.

While the European Central Bank’s interest rate hikes have significantly reduced inflation, economic growth across the eurozone remains uneven. Despite falling inflation and rising real incomes, Germany has emerged as a drag on overall eurozone growth, growing even more slowly than the UK—the only country to have left the EU.

Yet, the obvious question is: What was the main driver of these divergences? Was it the ECB's tightening, or were there other, more significant factors? Isabel Schnabel gave a speech last Friday outlining the ECB’s perspective on the causes of these divergences.

The ECB’s analysis is correct when Schnabel points out that output across all sectors, including capital goods (typically more sensitive to interest rates) in Germany, began to decline well before the ECB raised interest rates. Moreover, the ECB’s data shows that, on aggregate, German households have actually benefited from the rate hikes, as their debt remained mostly fixed while their interest income increased.

Schnabel argues that the recent trend of deglobalization and rising energy prices relative to other regions have played a significant role in the decline of Germany's export-driven growth model. Another key point she makes is that Chinese firms have moved up the value chain, producing higher-end goods, directly hurting their competitors in this space, such as German manufacturers.

Her conclusion that Europe needs reforms to support innovation and entrepreneurship is absolutely valid. However, her presentation suggests she may fall into the same trap as Mario Draghi regarding how to achieve this.

First, she promotes the idea that the eurozone, or Europe as a whole, needs to create a single market to facilitate the success of startups. While it's true that regulatory discrepancies between countries exist, one must remember that the founding idea of the European Union was to create a single market. This hasn’t been fully realized because wealthier countries are reluctant to reduce their market entry barriers and regulations. In comparison, poorer countries fear stifling their growth by implementing the same regulatory burdens.

Will the wealthier EU countries now agree to lower regulation? That’s highly doubtful, as Brussels is filled with lobbyists like Washington, DC. Business lobbies and other interest groups will always resist cutting regulations that increase competition for their members. Additionally, many member states are unwilling to transfer more power from the national to the Union level, even though this would be necessary to create a truly unified market. Given the EU’s track record of making business operations more complicated and not more accessible, it seems unlikely this approach will succeed.

Second, Schnabel argues that green innovation could drive growth if EU and eurozone countries ramp up investment in the sector. On the one hand, this is unsurprising, coming from a central bank that believes commercial banks must manage climate- and nature-related risks. On the other hand, it essentially repeats the mistakes that led to Germany’s current economic troubles. To Schnabel’s credit, she acknowledges the uncertainty of this approach in her speech:

The scale of these investments may require new financing ideas. Their costs, nd the uncertainty about future payoffs, are often so large that they may not break even over conventional investment horizons.

Therefore, she calls for increased public investment to support the transition. And that’s the core issue with all her proposals: the belief that politicians and economists can design a better economy on paper. In reality, her recommendations would lead to more centralization of power and economic decision-making. If history is any guide, this won’t result in a more robust economy but a weaker one—diverting resources from the private sector to the public, much like the GDR lagged behind West Germany.

In the end, the push for better economic conditions in the EU will likely result in EU officials seeking more power and resources to plan the economy centrally rather than allowing member nations to manage it themselves. This stands in sharp contrast to how the economic system in the US operates.

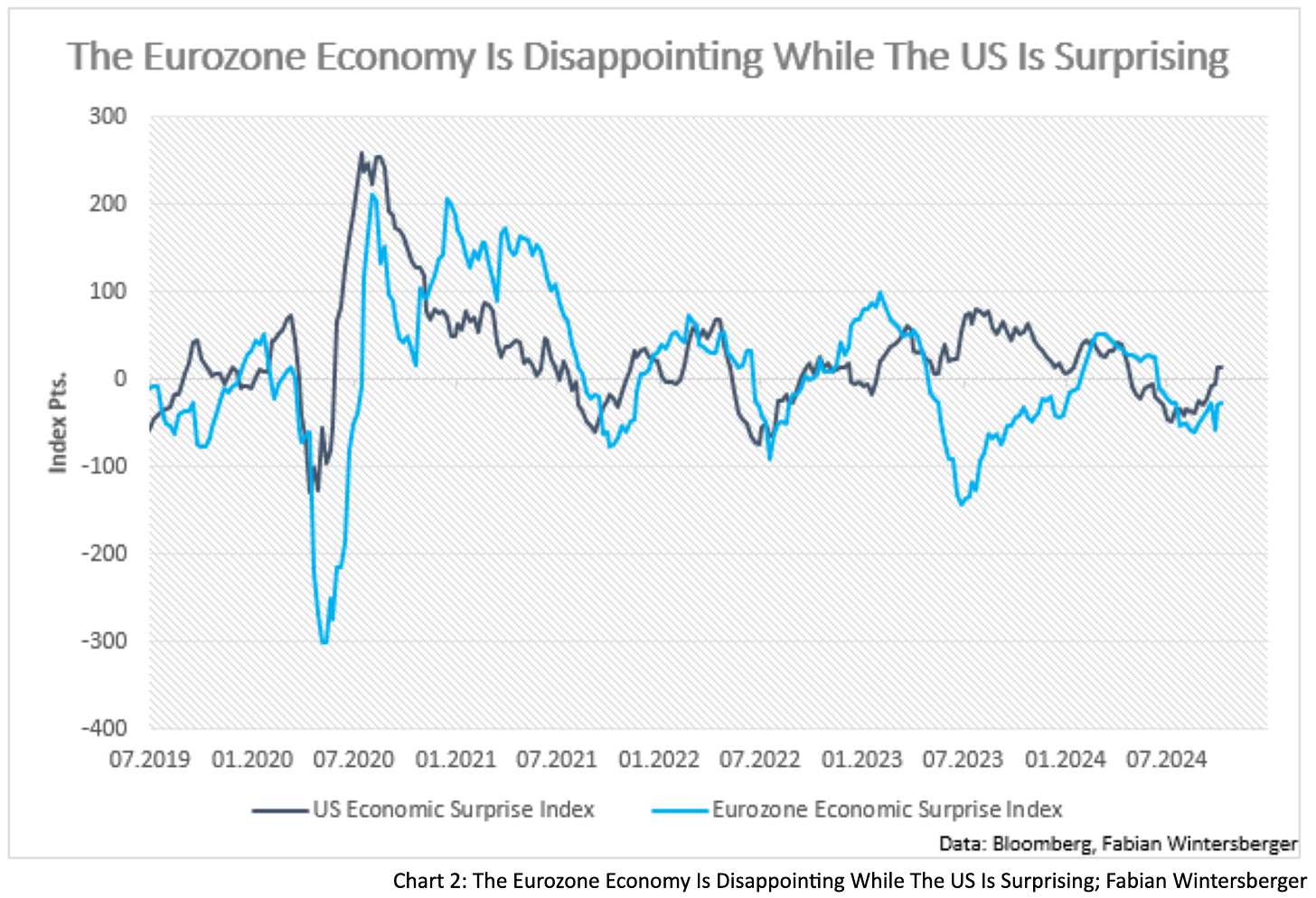

As a result, my outlook for the eurozone’s economic path remains pessimistic, not just in the short term but also in the long run. In contrast, the situation in the US looks quite different in the near term. Recent US economic data has exceeded expectations, while data from the eurozone has been disappointing, pointing to continued growth in the US while Europe remains stagnant.

In fact, last week’s nonfarm payroll data supported my argument that the US economy is not on the brink of a recession and continues to expand. The numbers were significantly better than expected. Instead of the median forecast of 125,000 new jobs, the US added 223,000. The unemployment rate fell from 4.2% to 4.1%, and the labor force participation rate held steady at 62.7%.

While average weekly hours worked dropped slightly from 34.3 to 34.2, the most notable point, in my opinion, is the increase in average hourly wages. Wages rose by 4% year-on-year, 0.2 percentage points higher than expected, and by 0.4% compared to the previous month, 0.1 percentage points above expectations.

Although some argue that a large portion of the job growth came from government hires and caution against taking the numbers at face value, I tend to push back on this notion when assessing the future trajectory of financial asset prices. The market tends to take the numbers as they are, and dismissing them in this context could backfire when analyzing future price movements.

Taking the data at face value supports my theory from last week that there is still a monetary cushion to sustain wage increases, keeping consumption and the broader economy going for longer. Employment is not deteriorating but somewhat normalizing, which is also reflected in GDP Nowcasts, which continue to project real annualized GDP growth above 3% for Q3.

The S&P 500 reached another all-time high this week, signaling two key points: the economy remains on an expansionary path, and there is increasing confidence in the Federal Reserve’s approach, including expectations for continued interest rate cuts. Despite the recent rise in long-term interest rates, this increase has been driven by short-term rates, which continue to price in substantial rate cuts over the next two years.

While current economic data does not support the likelihood of an aggressive rate-cutting cycle, I suspect that expectations have been primarily driven by the Fed and Jerome Powell’s comments at the last FOMC meeting. Although the decision was unanimous, the FOMC minutes released this week revealed a considerable debate over whether the Fed should cut rates by 25 or 50 basis points.

Some participants emphasized that reducing policy restraint too late or too little could risk unduly weakening economic activity and employment. A few participants highlighted in particular the costs and challenges of addressing such a weakening once it is fully under way. Several participants remarked that reducing policy restraint too soon or too much could risk a stalling or a reversal of the progress on inflation.

Reading through the transcript, one could get the impression that Powell played a significant role in the decision, possibly advocating for a 50bps cut instead of 25bps. Moreover, the minutes suggested that the Fed’s quantitative tightening is not likely to end anytime soon:

Several participants discussed the importance of communicating that the ongoing reduction in the Federal Reserve's balance sheet could continue for some time even as the Committee reduced its target range for the federal funds rate.

The committee appeared confident that consumer price inflation is on track to return to the Fed’s 2% goal. However, given the substantial 50bps cut at the September meeting, some participants highlighted the risks of continuing with more significant cuts:

Some participants noted that uncertainties concerning the level of the longer-term neutral rate of interest complicated the assessment of the degree of restrictiveness of policy and, in their view, made it appropriate to reduce policy restraint gradually.

This quote suggests growing concerns within the FOMC about the longer-term neutral rate (r*), which is the rate that would prevail if the economy were at full employment and inflation at the 2% target. Most economic models place r* around 2%, which implies that the current monetary policy rate is highly restrictive.

However, the problem is that the neutral rate is a theoretical concept that can only be estimated—no one knows precisely where it is. After the Global Financial Crisis, central banks drastically cut interest rates, arguing that r* had fallen for various reasons, at least according to their models.

Fed Governor Adriana Kugler, speaking in Frankfurt this week, highlighted this uncertainty, as Bloomberg reported:

“If downside risks to employment escalate, it may be appropriate to move policy more quickly to a neutral stance.” Where that neutral rate might be is unclear, she said, adding that the Fed is “way above it.”

So, the Fed is unsure where the neutral rate lies but is confident that the current Fed Funds Rate is “way above it”? That’s a remarkable statement with several implications for the future trajectory of asset prices.

First, if the Fed is wrong and the neutral rate is higher than it assumes, then-current policy is not as restrictive as it believes. This is supported by the fact that the stock market has reached new highs, and economic growth has remained resilient throughout the tightening cycle.

Second, this has significant implications for the yield curve. If the Fed and the market have incorrect expectations about the neutral rate, their interest rate forecasts are also wrong. The current inversion of the yield curve—where long-term rates are below short-term rates—reflects expectations that short-term rates are higher than future real growth and inflation, indicating the perceived restrictiveness of current policy.

However, the widespread assumption that an inverted yield curve signals markets are awaiting a looming recession is inaccurate. Historically, yield curves invert when short-term rates rise faster than long-term rates, not because long-term rates collapse.

Taking this further, the pandemic’s massive increase in the money supply has created imbalances in the economy, with funds circulating up and down over a more extended period. This could influence the potential growth rate and explain why the economy continues to grow at an extraordinary rate, impacting the equilibrium rate.

Since early October, long-term interest rates have risen despite many commentators claiming that being long bonds was a good bet. However, recent economic data releases have pushed yields higher again. The question is whether this rise is just a temporary move, with yields set to fall again, or whether the previous decline was an overreaction, anticipating a rapid economic slowdown in line with assumptions that rates are very restrictive.

However, the anticipated rate cuts are too optimistic if rates are not as restrictive as assumed. Long-term yields are too low and will likely need to rise further. If the Fed proceeds with rate cuts, long-term inflation expectations could rise, pushing long-term yields upward.

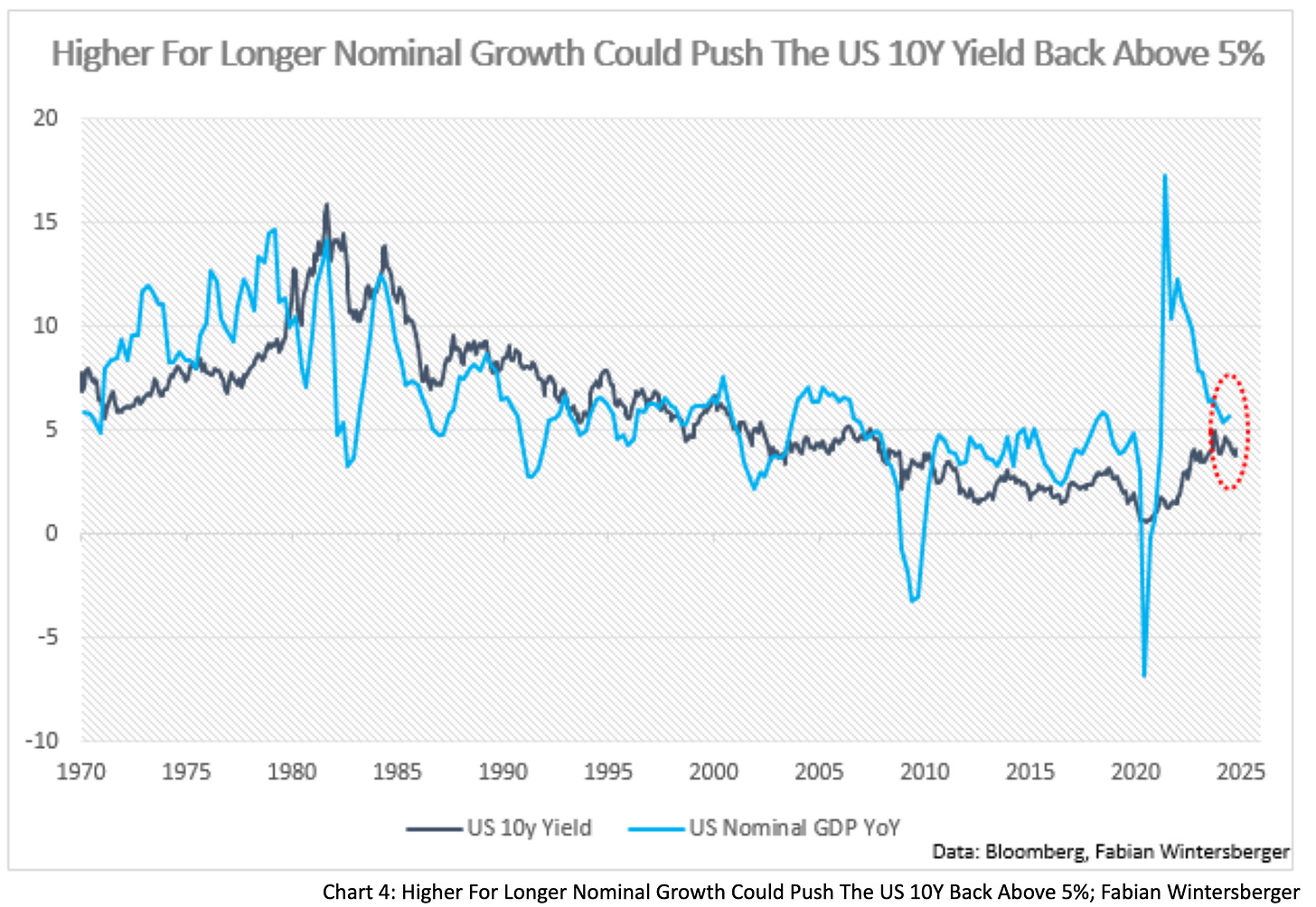

Historically, long-term interest rates have closely tracked nominal GDP growth. If the neutral rate is higher and monetary policy is less restrictive than the Fed thinks, falling inflation combined with rising real growth could keep nominal GDP stable, implying a rise in the 10-year Treasury yield back to 5-5.5%. In this scenario, it’s pretty possible that yields could rise to at least 4.5%.

Therefore, I believe there’s a good chance that the recent rise in long-term bond yields is just the beginning and that interest rates could continue to increase through year-end. Suppose the neutral rate is higher than the Fed and the market assumes. In that case, the current pricing of assets is distorted, and we may see a repricing phase, where bonds catch up with nominal GDP growth and the stock market benefits from the continued strength of the real economy, even as it anticipates a significant rate-cutting cycle.

This transition phase will end when interest rates reach a level where economic data begins to reflect real weakness, causing the yield curve to slope upward, stock prices to decline, and bond prices to rise. Forget about a soft landing—the current trajectory of the economy increasingly resembles a "no-landing" scenario, which will need to be fully priced in before the economy can be brought back down from the sky.

I've opened up my eyes, seen the world for what it's worth

Tears rain down from the sky

They'll blow it all to bits, to prove whose god wields all the power

Fire rains down from the skyTrivium – Down From The Sky

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for taking the time to read! If you enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to receive each post directly in your inbox. Additionally, sharing it on social media or giving the post a thumbs-up would be greatly appreciated!

All my posts and opinions are purely personal and do not represent the views of any individuals, institutions, or organizations I may be or have been affiliated with, whether professionally or personally. They do not constitute investment advice, and my perspective may change over time in response to evolving facts. It is strongly recommended to seek independent advice and conduct your own research before making investment decisions.