Circle With Me

You will never understand bureaucracies until you understand that for bureaucrats procedure is everything and outcomes are nothing ― Thomas Sowell

The ineffectiveness of their administrative systems has often shaped the rise and fall of empires. Initially designed to manage vast territories, these systems collected taxes, enforced laws, and facilitated governance. Over time, however, they often became sources of inefficiency, corruption, and stagnation, contributing to the empire's eventual decline. This pattern is particularly evident in Europe, where the legacy of ancient and medieval bureaucratic systems has profoundly influenced its modern economic landscape.

Take the Roman Empire, for instance, which laid the groundwork for many European states. While its bureaucratic system was advanced for its time, it eventually became a heavy burden. Managing an empire stretching from Britain to Mesopotamia necessitated a vast administrative apparatus. This complexity led to corruption, as officials often exploited their positions for personal gain, and inefficiency, as the bureaucracy struggled to respond to external threats, such as barbarian invasions or internal strife. These issues played a significant role in the fragmentation of the empire.

In the medieval period, the Holy Roman Empire offers another striking example. Its decentralized structure, composed of numerous princes and electors, each with its bureaucracy, led to overlapping jurisdictions and administrative chaos. This fragmented system impeded effective governance and stunted economic development, as local interests often took precedence over collective benefits, hindering trade and resource management.

The Spanish Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries encountered similar bureaucratic inefficiencies. Its sprawling colonial administration was plagued by delays in communication and vast distances, which granted colonial officials considerable autonomy. This often led to corruption and mismanagement, draining Spain’s resources and contributing to its economic decline, particularly when compared to more administratively streamlined nations like England and the Netherlands.

Though not strictly European, the Ottoman Empire had considerable influence over European territories and experienced its own issues with bureaucratic bloat. As the empire expanded into Europe, the bureaucracy became increasingly corrupt, with positions bought rather than earned. This inefficiency hindered the empire's ability to adapt to the industrial and Enlightenment-driven changes sweeping across Europe.

These historical examples underscore an essential lesson for Europe’s economic development: the need for administrative systems to remain flexible, transparent, and accountable. The bureaucratic structures that once facilitated empire-building can, over time, become obstacles to economic efficiency and adaptability, often accelerating the decline of the very systems they helped to establish.

Today, Europe seems to be confronting familiar challenges reminiscent of those faced by past empires. However, political leaders often make the mistake of thinking that a "better solution" to a problem is the answer without recognizing that many of these issues result from their policies.

With this in mind, I now turn my attention away from the dominant force in the global financial world—the United States—and focus on Europe, my home continent. Since the 2010s, and particularly following the COVID-19 pandemic, the policy responses and new regulations imposed by the European Union on its member states (many of which the UK continues to follow despite "Brexiting") have significantly reshaped the economic landscape.

As the third decade of the 21st century began, the pandemic brought the global economy to a standstill. Yet, as the economy gradually reopened and lockdown restrictions eased, it became clear that the economic environment had been profoundly altered. In particular, the tides appeared to have shifted across Europe. While Germany was the continent's economic powerhouse in the 2010s, it now faces a period of contraction, while peripheral nations have begun to outperform it.

What has happened to decisively turn the economic tide in favor of Europe’s periphery? Probably because of the recovery fund the EU implemented to address the economic fallout from government measures to combat the pandemic and the economic disruptions of the Ukraine-Russia war. The GDP figures clearly show who benefited most from these funds:

Italy, Spain, Poland and France stand to receive around half of the EUR 1.2trn redistributed by the EU to national governments in the period 2021-27 through recovery, cohesion and agricultural funds… The transfers will be particularly relevant for central and eastern European countries, Greece and Portugal, which will receive funds equivalent to between 25-40% of their 2021 economic output. – SCOPE Ratings

These economies have seen substantial GDP growth, which is expected, as government spending typically drives GDP upward, whether the spending is productive or not—a limitation of GDP metrics. This week’s S&P Global PMI for the Eurozone underscores the trend:

It was the currency bloc’s two biggest economies, Germany and France, which continued to drag on the union’s performance.

In light of this, it’s no surprise that Spain is Europe’s fastest-growing advanced economy this year. Its growth has been fueled primarily by rising government consumption and service exports, particularly tourism. Recent GDP figures show that EU countries with a stronger tourism sector are experiencing higher growth rates. Although the recovery fund was intended to boost productive investment, investment levels have remained below trend. Similarly, Italy has allocated a substantial portion of these funds to deficit spending in sectors like construction, which also inflates GDP.

This pattern—GDP growth driven by rising deficits—is not a novel “growth” model for the periphery. In fact, it mirrors the trajectory of the early 2000s. Notably, Greece has diverged from this trend, pursuing fiscal discipline. But for Italy and Spain, the story remains much the same.

Thus, the economic strength of the periphery can largely be attributed to the recovery fund and the resultant surge in government spending. Germany, meanwhile, also received some funds but faced unique economic challenges tied to geopolitics and domestic policies.

The Ukraine war fundamentally disrupted Germany’s industrial model, anchored in cheap energy and high wages. With the loss of Russian energy supplies, Germany has had to adapt more extensively than most European countries. By contrast, Spain and Italy, with more diversified energy sources, were less dependent on Russian gas and have benefited from their proximity to alternative suppliers. Industrial production data suggest that Germany, once Europe’s powerhouse, is now drifting toward the role of the “Sick Man” of Europe.

Germany’s most significant industrial challenge lies in its automotive sector, the most critical manufacturing sector. This sector, where workers earn relatively high wages, also drives demand in other industries, such as metal products, rubber, and plastics. However, the automotive industry has struggled significantly since the pandemic.

Firstly, Chinese automakers have grown increasingly competitive, capitalizing on Europe’s push for electric vehicles (EVs). China now dominates various segments within renewable energy and EV markets, largely thanks to massive government subsidies. In response, the EU parliament recently voted to increase tariffs on EV imports from China by up to 45.3% to protect European manufacturers.

Additionally, German automakers have been hurt by a decline in Chinese domestic consumption and a shift toward locally manufactured cars among Chinese consumers. This shift has reduced demand for German vehicles, driving German car exports down significantly from their levels in the 2010s.

Another potential challenge looms with the reelection of Donald Trump, as his trade policies could bring new tariffs on German exports to the US This year, the US became Germany’s largest trading partner as German manufacturers pivoted away from China. However, Germany’s economy is arguably more vulnerable than during Trump’s first term. While German automakers could theoretically shift production to the US to avoid tariffs, such a move would negatively affect domestic employment.

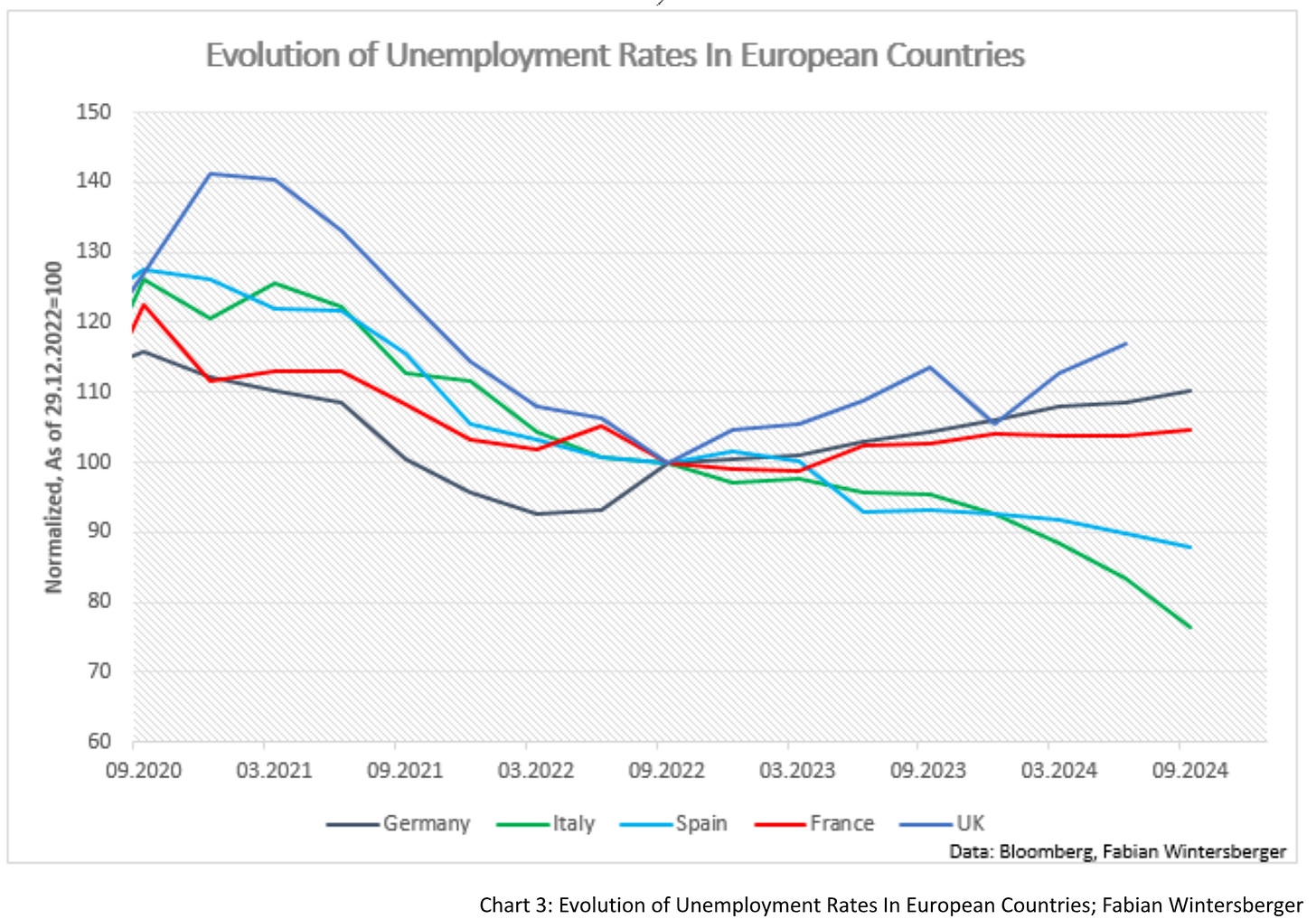

Germany’s unemployment rate has been steadily climbing since 2022 and is now approaching Italy’s, which, by contrast, has seen sharp declines. Looking at percentage changes since then, it’s clear that Germany faces mounting economic difficulties. Only the UK has experienced a more considerable relative increase in unemployment, though it started from a lower base.

Despite challenging economic conditions, the German DAX has outperformed the EuroStoxx year-to-date. However, it's worth noting that the most significant gains within the index stem from just a few companies: SAP and Siemens (these two alone represent 20% of the index), Rheinmetall, MTU Aero Engines, and Commerzbank. In contrast, other industrial producers and automakers have experienced losses this year. At present, finding a medium-term bullish case for both Germany and Europe as a whole remains difficult. The debt-financed boom in many peripheral states will likely reach its limit eventually, which could cause further complications.

However, the economic outlook seems less grim in the very short term. While PMIs suggest the economy isn't yet expanding, sentiment has improved:

The seasonally adjusted HCOB Eurozone Composite PMI Output Index – a weighted average of the HCOB Manufacturing PMI Output Index and the HCOB Services PMI Business Activity Index – recorded 50.0 in October, which indicates no change in private sector output levels when compared with the month prior. This did mark an increase from 49.6 in September but was well beneath the survey average of 52.5.

I tend to believe that this trend could continue through year-end, though this forecast comes with substantial uncertainty. Trump's recent win has also pressured German automakers and suppliers more. However, the service sector is driving sentiment improvement, and falling inflation, coupled with rising real wages, could provide short-term economic support.

German Economic Minister Christian Lindner also seems to have taken note. Suddenly, his liberal party, the FDP, realized the German economy was struggling—perhaps due to the devastating losses the FDP had seen in recent polls, which suggested that it might not be reelected to Parliament.

Last weekend, a document leaked to the media in which Lindner called for a significant U-turn on various economic policies. In the paper, Lindner advocates for a market-based approach to improve economic conditions, including deregulation, tax cuts, and a slower path to emissions reduction.

These proposals contrast starkly with the coalition's actions since its inception, which the FDP has always supported. While growing tensions within the coalition weren’t surprising, it was unexpected to see Lindner push his proposals to the extreme by suggesting early elections in 2025. Scholz rejected this and, half an hour later, dismissed Lindner from his government post.

Before the press, Scholz seemed bitter, harshly criticizing Lindner for “repeatedly betraying” his trust, while Lindner accused Scholz of preparing his dismissal statement in advance. Lindner added that his party remains open to joining a future government. Scholz, meanwhile, plans for the current government to continue until January when he intends to hold a vote of confidence in the Bundestag.

This situation has thrown Germany into a full-blown policy crisis, with numerous potential outcomes, the most likely early elections. Ironically, given that the government has arguably worsened Germany’s economic situation, businesses might actually benefit if no further harmful policies are implemented for now.

While we must continue monitoring developments in Germany, there is a growing consensus across parties that economic policy changes are essential—and this sentiment extends beyond Germany. EU leadership under Ursula von der Leyen has recently acknowledged that Europe's economy requires adjustments.

Yet it seems likely that EU leadership will still fall short of the necessary changes, even though the Draghi Report contains valuable insights. My earlier assessment remains that the EU will probably reject the most reasonable proposals in the Draghi Report and focus on less favorable options like joint debt and trade barriers.

From a long-term perspective on European politics, we may see some softening of recent decisions—such as delaying the end of combustion engines or net-zero targets—but the EU’s top-down approach is unlikely to change.

The most criticized aspects of the Green New Deal for German businesses are the (already diluted) supply chain laws, which impose an enormous bureaucratic burden. Companies must map and track their supply chains to ensure every step aligns with the current EU ESG taxonomy.

Though these policies are arguably justifiable from a moral standpoint, they pose several economic challenges. First, they increase bureaucratic and administrative costs for companies, requiring resources that could otherwise be used productively.

Second, they favor large companies that can afford extensive compliance, while SMEs may be disproportionately impacted, potentially threatening the so-called "backbone" of the economy.

Supporters argue that these regulations, though costly in the short term, could attract ESG-oriented investments in the long term. However, this reasoning is flawed. Profitability itself often indicates sustainability because high profits typically reflect efficient, resource-conscious capital use.

Nevertheless, when considering this argument further, it's evident that laws like these shift sustainable investment away from market forces and into political decision-making. As a result, investment decisions are guided more by government planning than the private sector (even as EU government spending already accounts for roughly 50% of GDP).

Government spending, however, is funded by two sources: current or future taxation (i.e., borrowing). Since taxation in the EU is already significantly higher than in other regions, further tax hikes seem unlikely to fund rising government investments. As Lindner aptly warned, politics is now leaning away from market-based solutions toward planned governance, with ESG policies becoming a tool to direct investment—raising the question: where will the money come from? Likely, from the ECB.

This context clarifies why ECB head Christine Lagarde has endorsed the central bank’s role in advancing Green New Deal goals. Like businesses, banks must also comply with ESG standards, such as assessing transition risks, physical climate risks, and a green asset ratio.

ECB Executive Board Member Frank Elderson has already cautioned banks to implement these “transition risk” measures more proactively. While technical in language, the implication is that banks should prioritize lending to businesses that adopt these standards, or as the ECB would put it, “price-in” climate risks in their loans. A recent ECB working paper confirms that this policy is now embedded in lending standards:

Combining euro-area credit register and carbon emission data, we provide evidence of a climate risk-taking channel in banks’ lending policies. Banks charge higher interest rates to firms featuring greater carbon emissions, and lower rates to firms committing to lower emissions, controlling for their probability of default.

Although this aims to incentivize sustainable practices, it comes at the cost of pushing “good” behaviors and penalizing “bad” ones, as defined by policy. This path leads toward a European version of a social credit system. In fact, policies from the EBA and ECB resemble aspects of China’s government framework (emphasize mine):

Instead, the system that the central government has been slowly working on is a mix of attempts to regulate the financial credit industry, enable government agencies to share data with each other, and promote state-sanctioned moral values—however vague that last goal in particular sounds... Basically, the Chinese government is saying there needs to be a higher level of trust in society, and to nurture that trust, the government is fighting corruption, telecom scams, tax evasion, false advertising, academic plagiarism, product counterfeiting, pollution …almost everything. And not only will individuals and companies be held accountable, but legal institutions and government agencies will as well.

Though the cited article acknowledges that some regions in China have implemented personal social credit scores, it astonishingly argues that a centralized social credit score doesn’t exist and is unlikely to be implemented—though the author admits that certainty on this point is impossible. In the EU, the threat is similar, as the Green Deal basically created the necessary infrastructure to implement such a system.

To conclude, despite the current economic challenges in Europe and some efforts to mitigate the impact of additional regulations on businesses, the EU and the ECB continue to pursue the development of a system that rewards "good" behavior in businesses and banks while punishing "bad" behavior.

Economically, these measures drive up administrative costs for businesses, making European companies less competitive than their global counterparts. With Trump’s election, the US will likely pursue these goals much less aggressively, bolstered by public support for personal and economic freedoms.

While some European leaders have acknowledged the need for policy adjustments, their actions are unlikely to resolve Europe’s economic problems. Future elections may allow Europeans to vote for parties that oppose the current policies, but realistically, the chances for significant economic reform remain slim.

The recent economic improvements within the Eurozone may persist but could prove short-lived. As long as politicians remain unwilling to embrace market-based solutions, ECB rate cuts will provide little more than temporary relief.

Historically, well-intentioned political interventions have often resulted in more significant economic hardship. The typical response to the consequences of such interventions has been more interventions rather than rethinking existing policies. This diverts resources into unproductive activities and stifles innovation.

Thus, while the US is experiencing an AI boom and SpaceX has achieved the groundbreaking feat of completing the world’s first rocket landing, European innovation remains nonexistent. In Europe, the EU Commission celebrates its AI Act as if it were a monumental achievement akin to landing on the moon. As long as this situation persists and EU countries fail to recognize the need for a return to free markets. The European economy will remain in economic stagnation.

Feel the weight of a martyr,

It could all be yours if you echo birds of prey.

Traitor cut down the altar,

It could all be yours, vultures circling the flame.Spiritbox – Circle With Me

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for taking the time to read! If you enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to receive each post directly in your inbox. Additionally, sharing it on social media or giving the post a thumbs-up would be greatly appreciated!

All my posts and opinions are purely personal and do not represent the views of any individuals, institutions, or organizations I may be or have been affiliated with, whether professionally or personally. They do not constitute investment advice, and my perspective may change over time in response to evolving facts. It is strongly recommended to seek independent advice and conduct your own research before making investment decisions.

Thanks Fabian, very good exercise about our economical plagues.

Those are not only economical, imo, but put also question about our democracies

Fabian, I think you understate the potential problems coming for the Europeans on the back of their Green efforts. clearly, neither China nor India care at all about the green concept, with China merely taking advantage of their government supported manufacturing process to build things more cheaply than the west that the west wants but china doesn't. However, now with the Trump election, you can be sure that the US is not going to care about green issues at the government level, which means that European banks, if they are going to compete with US banks, will find themselves hamstrung by the needs of determining second and third order emissions while US banks will not need that.

On a separate note, you discuss the fact that GDP growth represents government spending for so many countries, and that is, of course, true in the US as well. how can one remove the G from the GDP equation to determine the value of private sector activity and growth?