Bulletproof

It is, after all, only common sense to realize that, but for the fact that economic life is a process of incessant internal change, the business cycle, as we know it, would not exist – Joseph A. Schumpeter

Berlin, in the early morning of November 20th. In the official residence of the president of the Reichsbank, an eventful and lengthy career in German public service is finally drawing to a close. Just the day before, the public servant believed he was recovering from the flu and decided to resume work. He dictated a final letter to German Reich President Ebert, reiterating why he and his deputy found it impossible to step down from their positions.

However, over the night, his condition deteriorated, and around 3 a.m., Rudolf Havenstein's heart ceased beating. At the age of 66, his life and career as the president of the Reichsbank ended. Some remember him as the worst central banker in the 21st century. Financial historian Neil Irwin even went so far as to label him the worst central banker of all time.

Havenstein, a lawyer, assumed the position of president of the Reichsbank in 1908. As the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung noted in its epitaph in 1923:

Before the Reichstag, he immediately identified himself as an opponent of nationalization and a firm supporter of the gold standard - a treasure that, however, did not have to be preserved for the German people but - there is no doubt about it - had to be given up during the war. He manfully represented his view of the value of a strong, efficient stock market. Even their periodic exaggerations do not confuse him, although he took strong action against them at times when it was necessary. His goal became, more and more, to increase the liquidity of the national economy at that time.

Yet, Havenstein should not be solely remembered for that. When the First World War erupted, the Reichsbank had no choice but to abandon the gold standard and finance government expenditures through the printing press. After all the warring parties experienced an inflationary post-war period, Havenstein and the Reichsbank diverged from the paths most other central banks took. They continued to print money, creating an artificial economic boom and fueling speculation. Stock prices surged fourfold between February 1920 and November 1921. Mergers and acquisitions skyrocketed, leading to a shift of workers from productive to unproductive sectors.

While the German Mark became the most valuable currency in the world, the consequences of the Reichsbank’s actions were unavoidable. Prices soared repeatedly, quadrupling every week in 1923. The cost of a Schnitzel increased by 20% between ordering and paying the bill.

Havenstein was trapped in the belief that money printing wasn't the cause of inflation. Alongside many politicians and entrepreneurs, he believed the negative trade balance was the root cause of inflation, and the Reichsbank needed to print money in response. British ambassador Edward V. D’Abernon attempted to convince prominent figures that this perspective was flawed but did not succeed.

Nobody wanted to believe that a man with such a great reputation and the backing of the entire Berlin banking world could be completely wrong on an issue of such importance.

Until then, Havenstein complied with the government's directives despite the Reichsbank gaining independence in mid-1922. However, as more politicians sought Havenstein's removal, he became aware of this sentiment and used it to argue for his irremovability. Although seemingly bulletproof, the German government simply established a new central bank that introduced a new currency, the "Rentenmark," on November 15th, 1923. During this period, Havenstein was already ailing from the flu, and five days later, he passed away, coinciding with the demise of the Mark.

Even though Havenstein couldn't be ousted from his position, in the end, he was not impervious, despite his belief to the contrary. Today, just as many analysts who predicted a recession in 2023 are adjusting to the current reality, similar to Havenstein, they perceive the market as more or less invulnerable.

Since last week, bond and stock prices have seen a slight uptick, indicating ongoing strength. The euro also continued its appreciation against the dollar earlier this week and is now unchanged compared to Friday's close. Economic data releases remain mixed, but overall, the US economy is holding up better than anticipated at the beginning of this year.

Consequently, market participants have embraced the central banks' rhetoric as accurate and anticipate that interest rates will remain elevated for an extended period. Market participants expect only gradual rate decreases from the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank in the second half of next year.

What's noteworthy here is that market participants do not harbor distinct expectations for the Fed and the ECB. If anything, the recent movement in EUR/USD could bolster the argument that market participants believe the ECB will cut interest rates simultaneously with or after the Fed. The rationale behind this perspective may be rooted in the ECB's historical pattern of raising interest rates after the Fed, implying a tendency to follow the Fed's lead.

This viewpoint gains additional support when examining public debt-to-GDP ratios. Governments in the Eurozone collectively maintain a debt/GDP ratio of around 90%, while the US's debt-to-GDP ratio approaches 120%. However, I would caution against viewing this perspective as farsighted, as the US benefits from the privilege of issuing the world's primary reserve currency.

Moreover, when considering individual states, debt levels in the Eurozone surpass those in the US. In the US, Kentucky boasts the highest debt/GDP ratio at approximately 21%, whereas in the Eurozone, Greece and Italy exhibit the highest debt/GDP ratios at 168% and 144%, respectively. This disparity arises from the fact that, unlike the US, the Eurozone/EU cannot independently issue debt.

Setting aside the differences in the composition of public debt in the US and the Eurozone, a divergence also exists in economic conditions. While the US economy continued robust growth in Q3 at a very high level, the Eurozone economy is already grappling, particularly the German economy. In addition to exceptionally high energy prices, the weakened Chinese economy poses a challenge for European producers, given that China is Europe's foremost trading partner.

Although the recent appreciation of the euro is providing some relief to Eurozone countries by making goods purchased in dollars on the world market more affordable, the potential rebound from this development appears unsustainable. On a sovereign level, EU countries have significantly increased government spending to combat the energy crisis, with projected budget allocations exceeding what is permitted by EU rules.

Moreover, the current disinflation is more indicative of economic weakness than an improvement in economic conditions. Over the medium term, the economic contraction could intensify, pushing Eurozone countries further into debt relative to their GDPs.

It seems that market participants may be underestimating the potential deterioration of the economic situation in the Eurozone. Consequently, the considerable fiscal deficits in many Eurozone countries suggest that the ECB may be compelled to act sooner than the US. This is why I view short-term European yields as a potential opportunity to benefit from the anticipated ECB rate cuts.

On the longer end, the situation is challenging because the ECB's drastic loosening of monetary policy to support the economy could lead to higher energy prices. Unlike the US, Europe is a net energy importer due to its NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) policy. The weakening opposition to nuclear energy will likely be beneficial in the long run but may not provide immediate relief.

Hence, if inflation remains around or slightly below the two percent level, it could increase long-term inflation expectations, influencing expected real yields for longer durations. Therefore, in my opinion, investors should focus on the short end rather than the long end.

While the euro has appreciated against the dollar in the last two weeks, it is now approaching a level that I consider suitable for entering a short position. Sentiment has also become very dollar-bearish, as is typical around turning points.

My perspective remains that the US is nearing a recession and probably will enter one in the current quarter. Empirical data supports the idea that the US yield curve is a reliable recession indicator. Although many analysts look at the 10-year-2-year spread, the Fed considers the 10-year -3-month spread as an indicator.

While the 10-year-2-year spread inverted in July last year, the 10-year-3-month spread began to invert in November last year. Therefore, although I stand by my call from this year, it is possible that it will take a little longer, and the recession may start in Q1 or Q2 next year, depending on which yield spread one is considering.

This week's Fed Minutes reveal that several members of the FOMC observed at the November meeting that certain households' finances are strained due to elevated prices for essential goods and more stringent credit conditions. Additionally, some members highlighted the concern that the aggregated data may present a misleading picture, suggesting that consumer demand might be worse than indicated.

As per the Minutes, economic conditions are not only tightening for consumers but also for businesses:

Business fixed investment was flat in the third quarter, and participants observed that conditions reported by their business contacts varied across industries and Districts. Some participants noted that businesses were benefiting from an increased ability to hire and retain workers, better-functioning supply chains, or reduced input cost pressures. A few participants commented that their business contacts had reported that cost increases could not be easily passed on to customers. Several participants commented that the apparent resolution of the United Auto Workers strike would reduce business-sector uncertainty. Several participants noted that an increasing number of District businesses were reporting that higher interest rates were affecting their businesses or that firms were increasingly cutting or delaying their investment plans because of higher borrowing costs and tighter bank lending conditions

So far, the data sends mixed signals, leading market participants to interpret things positively for financial markets. This interpretation is driven by the assumption that the Fed has concluded its interest rate hikes. Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the prevailing consensus suggests a gradual economic slowdown in the coming year, though nothing overly severe. This could imply that the stock market will likely continue to perform well or, to put it differently, may still experience further gains. It's essential to note that when the stock market struggles to ascend and becomes range-bound, that signals a time to adopt a more defensive stance, even though sentiment has recently become somewhat stretched.

On the bond market, however, the situation differs somewhat this time. Despite a successful 20-year Treasury bond auction, yields did not decline significantly. According to Saxo Bank's Althea Spinozzi, one possible reason for this could be that

…leverage funds have been reducing their short bond position dramatically in the past few weeks and are now the least short since July.

With the dollar retaining its status as the major reserve currency, there continues to be a significant amount of domestic and foreign demand for US Treasuries, particularly in light of rising interest rates. However, there are noteworthy aspects to consider, in my opinion. Firstly, the Bank of Japan might finally loosen its grip on its sovereign bond markets, indicating a potential tolerance for a further increase in JGBs.

Japanese investors have been substantial buyers of Treasuries for decades, benefiting from higher yields in the United States. Nevertheless, as interest rates rise in Japan, domestic bonds become more attractive relative to foreign bonds. This shift could impact the demand for US Treasuries. Suppose Japanese investors redirect their focus to domestic bonds. In that case, demand for US Treasuries might decrease, leading to higher yields and potentially tempering the "flight to safety" trade (buying long-duration bonds) in the event of a US recession.

Despite these considerations, many investors seem to dismiss their significance, holding the belief that US treasury bonds inherently generate their own demand. This perspective aligns with the MMT fallacy promoted by figures like Warren Mosler and Stephanie Kelton. Kelton recently shared on social media:

Them: We have to deal with America's debt problem.

Me: So you want to prevent holders of US dollars from shifting those dollars from checking to savings accounts at the Fed?

Them: I don't know what that means.

Me: That's the problem.

Kelton asserts here that someone who purchases US Treasuries is essentially generating additional currency units that the Treasury can spend while retaining the funds in their bank account. However, this notion is a misconception because the bond buyer no longer possesses the money; instead, they hold a document stating that the US Treasury owes them money. At best, individuals may exchange it based on its net present value. At worst, it circulates like a hot potato until someone cannot find another buyer for the paper, and the music stops playing.

If Kelton's statement were universally true, it would apply to every loan and bond issued. In theory, the lender simply transfers dollars from a checking to a savings account. However, this oversimplification doesn't align with reality, as evidenced by credit scores and credit spreads. Borrowers must have the capacity to repay what they borrow.

However, proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) and, consequently, all heterodox Keynesians argue that it's different for the state because it issues its own currency, eliminating concerns about repayment. While this statement is factually correct, it doesn't guarantee that investors will always be willing to buy treasuries. Similar to hesitations about purchasing junk bonds, investors may perceive that the spread doesn't accurately reflect the risk of default. Furthermore, in the end, real income is crucial. Although the US Treasury can always repay in nominal terms, inflation may lead to significant losses in real terms.

Another possibility is default, where the Treasury fails to fulfill its obligations to investors due to malinvestment. As we know, governments are adept at spending money on interest groups but may struggle to invest and create sustainable growth.

Here's where the problems become apparent. If it is indeed true that all government debt represents a surplus in the private sector, the return on investment should be close to one, indicating that every dollar invested creates a dollar of GDP. However, plotting nominal GDP against government debt reveals that the government struggles to stimulate growth and fund its issuance through additional economic growth.

It's a reiteration of the age-old notion that deficits will somehow fund themselves, a concept formulated by Keynesians more than half a century ago. Perhaps the most compelling evidence that this idea doesn't hold water can be found in the period from the sovereign debt crisis to the COVID pandemic in Europe, where accumulating additional debt failed to spur growth.

I've previously discussed the potential for fiscal dominance, emphasizing that governments will eventually need to bring down their debt-to-GDP ratios to sustainable levels. Recent moves by Canada and Germany to halt the issuance of inflation-protected securities suggest that governments are becoming increasingly aware of the necessity to address their debt levels.

Germany, in particular, has been inventive in concealing government debt, resorting to creating "off-budget" funds. However, recent legal challenges, such as the German national supreme court ruling against repurposing pandemic aid for climate protection spending, have exposed the limits of such strategies. The decision to stop issuing inflation-protected securities aligns with the idea that inflation might be viewed as an effective tool by policymakers, potentially indicating an acknowledgment of the inflation tax as a means to ease debt burdens.

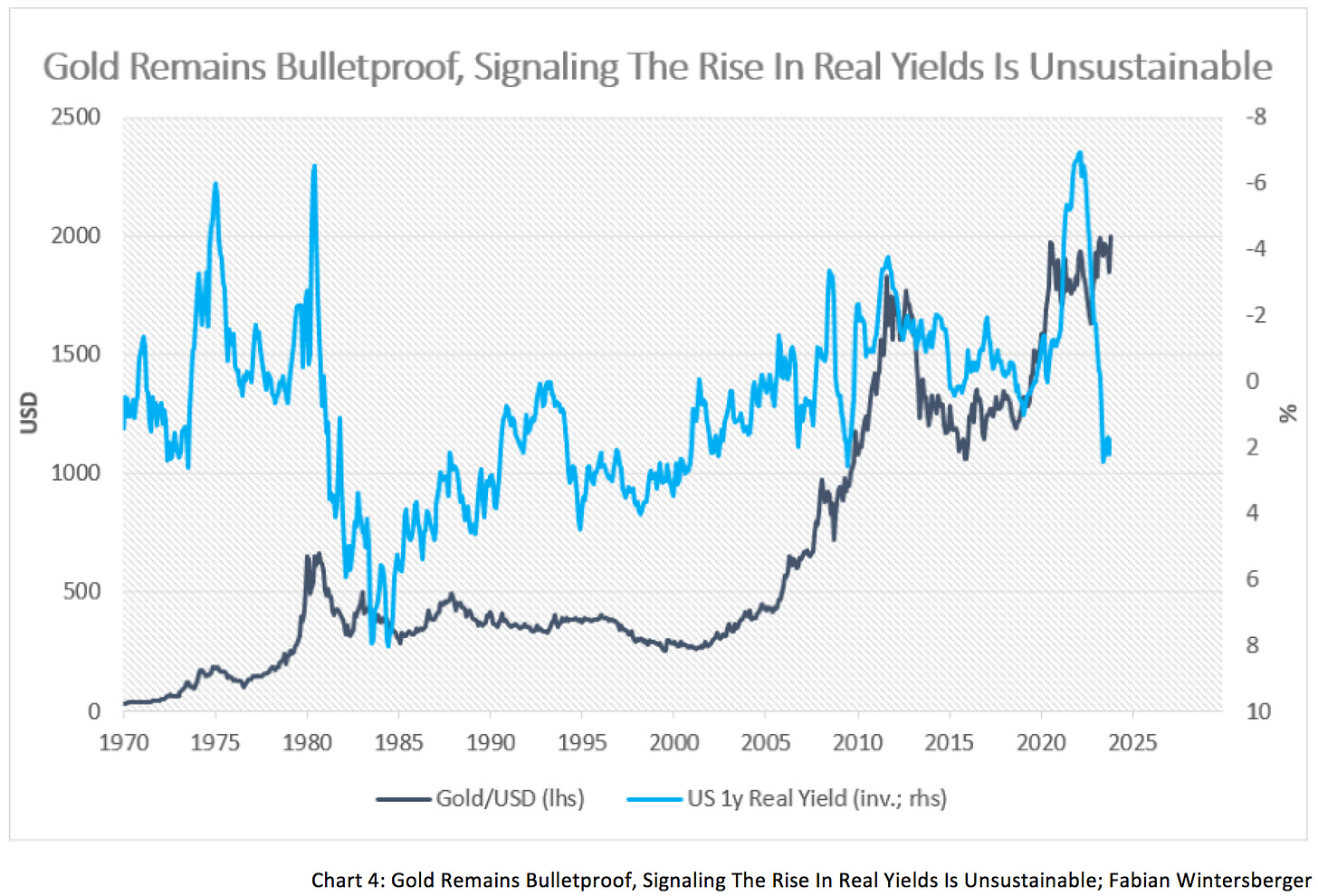

As evidence mounts that governments are leaning towards inflation rather than spending cuts, it could explain the resilience of certain assets to rising real rates, particularly gold. Despite falling inflation and steady nominal yields that elevate real yields, gold continues to hold its ground. Some investors may have already anticipated government strategies, making it sensible for mid or long-term investors to consider buying into gold during market dips, especially as a portfolio protection strategy.

Looking ahead to the rest of the year, I expect Eurozone economies to contract further while the US inches closer to the brink of recession. The stock market, driven by seasonal and cyclical factors, is anticipated to remain robust, potentially experiencing further growth. This strength in the stock market should support bonds across the curve. However, given the extraordinary circumstances marked by high rolling deficits, a preference for the short end over the long end is maintained, as yields on the long end might not decline as significantly as some assume.

Ultimately, the question remains: What's more bulletproof, real economies, the stock market, or gold? Only time will tell…

Now that you want it, now that you need it, I’m too far gone

You’re trying to blame me, but I’m not breaking

I’m telling you, I’m bulletproof, believe me I’m bulletproof

You make me so bulletproof, and now I’m too far goneGodsmack – Bulletproof

Have a fantastic weekend! Special Thanksgiving wishes to those in the US!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for taking the time to read! If you enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to receive each post directly in your inbox. Additionally, sharing it on social media or giving the post a thumbs-up would be greatly appreciated!

(Please note that all posts reflect my personal opinions and do not represent the views of any individuals, institutions, or organizations I may or may not be professionally or personally affiliated with. They do not constitute investment advice, and my perspective may change in response to evolving facts.)

There certainly seems to be some cognitive dissonance in the markets, with the strong belief in an ongoing equity rally along with bonds, along side weakening economic activity. after all, why would the Fed cut if the economy remains strong and can seemingly handle the current level of rates? it definitely feels like something is going to break pretty soon