Blind

Markets Fly Blind as Fed Guesses at Shadows

If the blind leads the blind, both will fall into a ditch - John 16:33

Good news first. Democrats and Republicans finally struck a deal to end the government shutdown—one of the longest in history. The bad news for market watchers is that October CPI and NFPs may share the Epstein files’ fate: they’ll probably never see the light of day.

Hence, without government data being released, the market continues to operate mostly in the dark regarding inflation and the job market. The only reference point for the job market is the ADP numbers, which suggested that the job market continued to weaken in the second half of October.

US companies shed 11,250 jobs per week on average in the four weeks ended Oct. 25, according to data released Tuesday by ADP Research.

If we examine the price action across asset markets this week, the most notable thing that caught my eye was that the dollar weakened and gold strengthened. The question is whether the dollar weakness remains temporary, as I believe, or whether it will be around for longer. Either way, the DXY bounced off its resistance at 100, and therefore, it seems to pay off to be patient here. It is possible that the DXY will return to 98 by year-end.

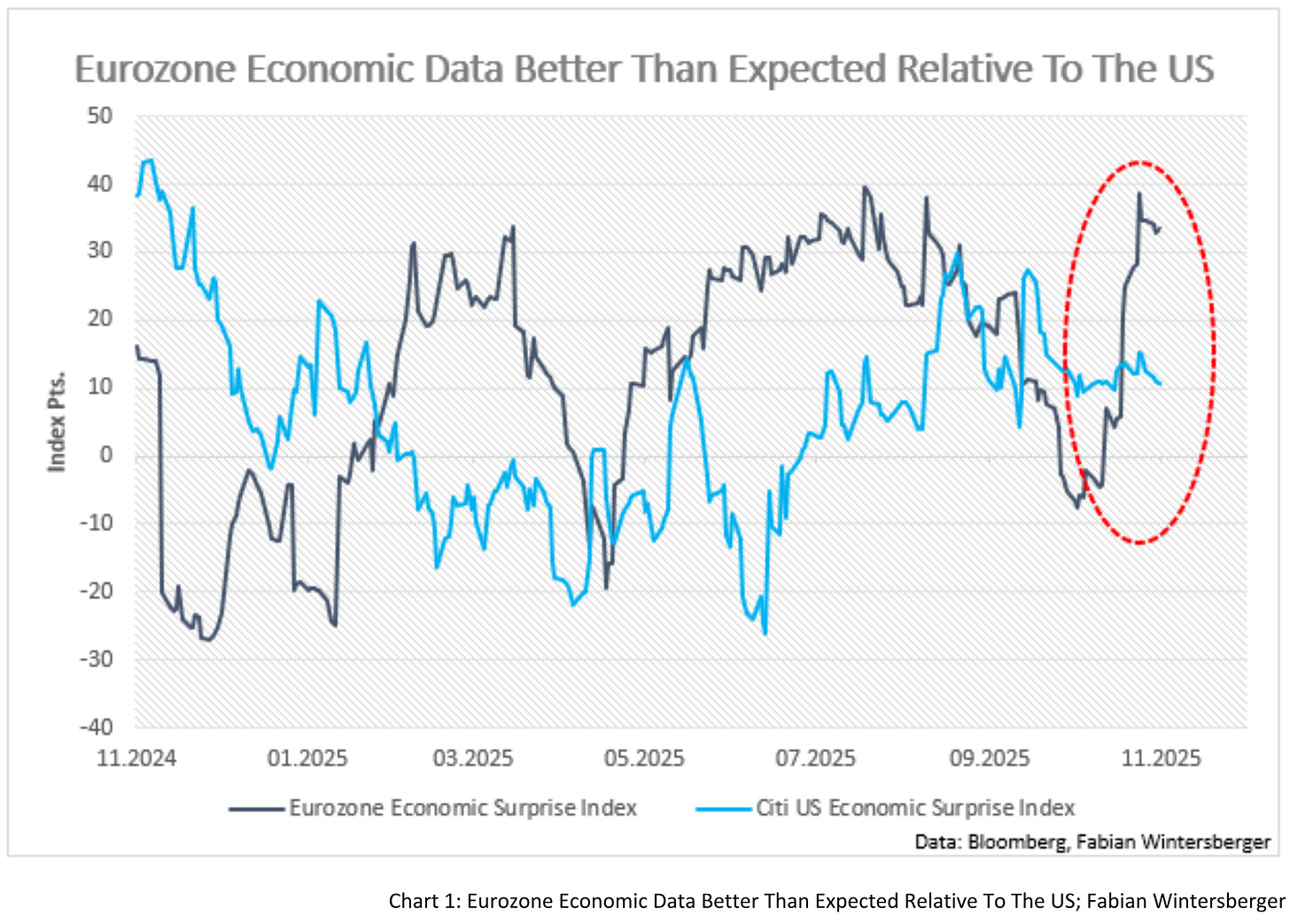

One reason is that European economic data is surprising to the upside compared to the US economy. The difference between the two economic surprise indices might encapsulate why the dollar rally has stalled lately.

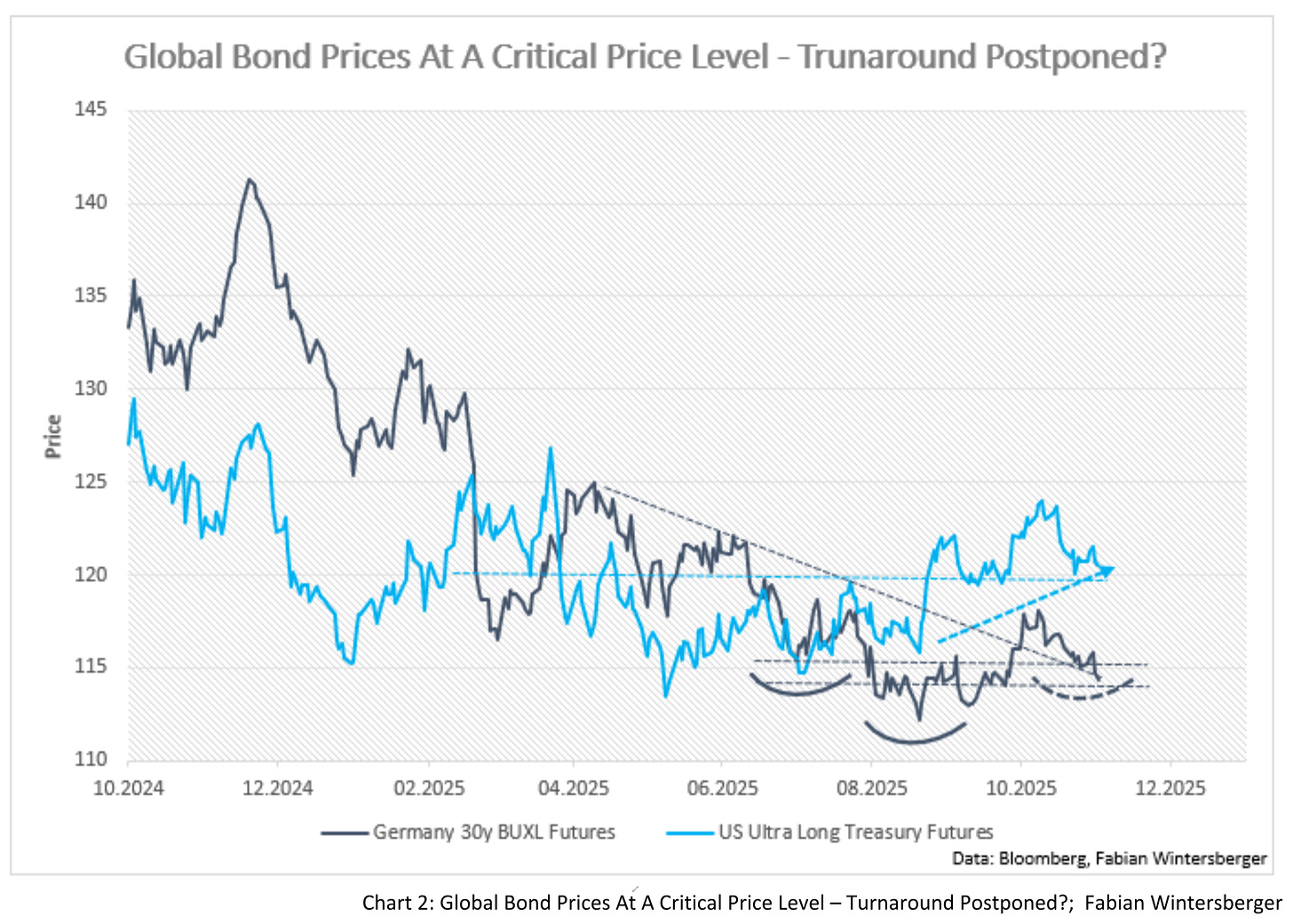

The other thing that got my attention this week was the bond market. Last week, I wrote that bond prices are reaching a critical resistance, and a further drop would prompt me to reconsider my current view on bonds. Bonds indeed sold off on Friday, but bulls managed to defend the resistance. The German 30-year BUXL Futures have steadily increased since then, albeit the price action still appears to be driven by US interest rates. However, without any substantial news, Thursday triggered a sell-off that pushed bonds below this week’s lows, approaching the critical resistance line once again.

Nevertheless, the situation didn’t really change: a substantial drop below 114 could trigger more selling. At the same time, a further increase could support my thesis that a turnaround in German bonds is underway and join US long-term bonds in their upward trend. I think that within the next few days, the price action in bonds will give a clearer picture of where we’re heading.

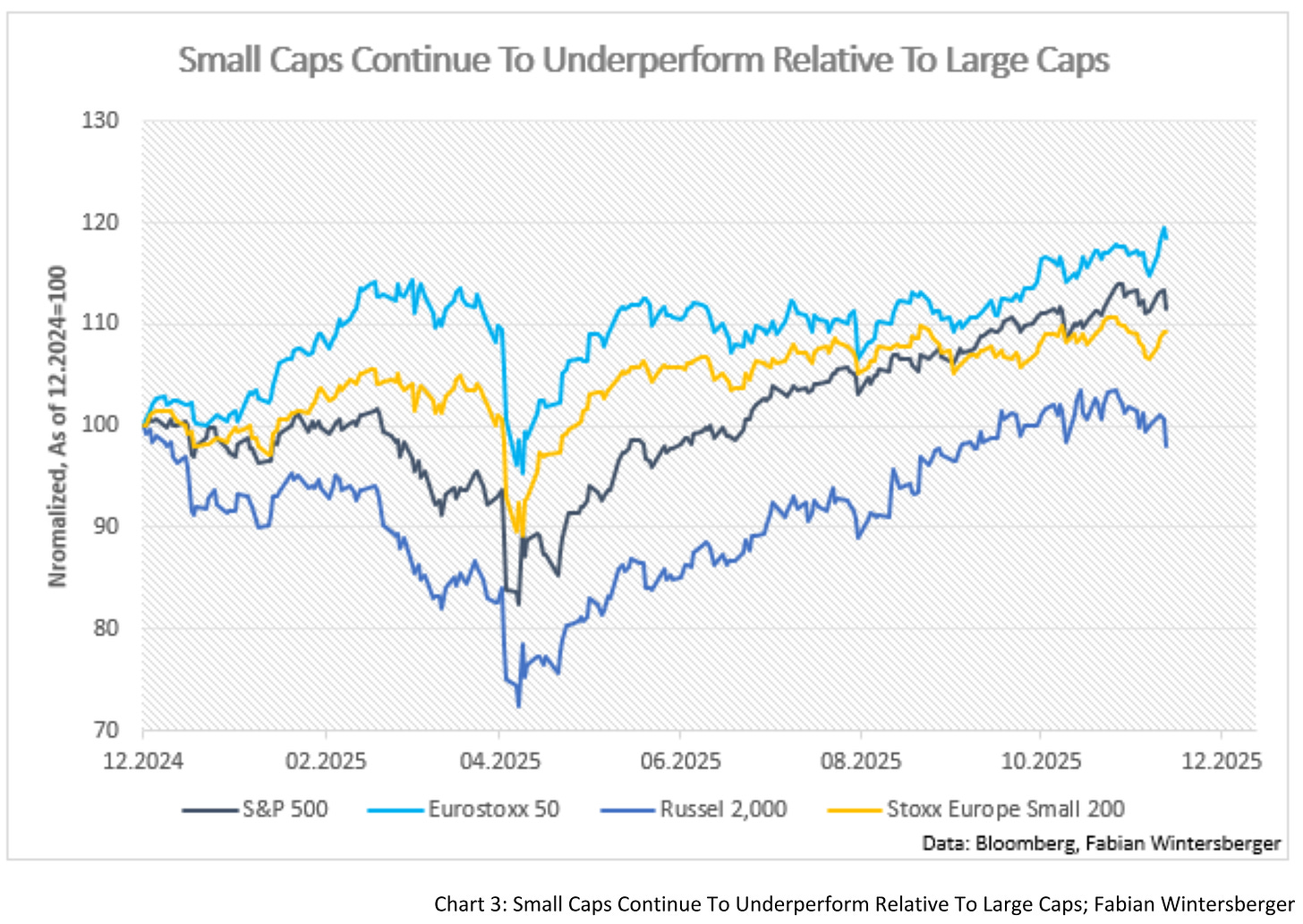

To sum up the analysis of the price action this week, let’s move on to the stock market. While my general view on stocks has been confirmed so far, the idea that small caps might finally catch up with large caps has not come to fruition. The S&P 500 and the Euro Stoxx 50 continue to outperform small-cap indices.

However, the chart picture of small caps could suggest that they are forming a top at the moment. While I’m not yet convinced that it’s over for small caps in this cycle, a further drop would falsify that thesis. Yet, the thesis is getting weaker, as a strong sell-off on Thursday brought US small caps back to a critical price area.

Apart from the current trajectory of markets, recent comments of Fed officials caught my attention this week. Stephen Miran and John Williams gave some interesting comments about the “neutral interest rate,” the rate at which monetary policy would neither be expansive nor restrictive.

Miran gave a long-form interview on the Monetary Matters podcast, where he laid out his case that Trump’s trade and migration policies led to a significant drop in the neutral rate. According to his estimations, he argues that the neutral rate is about 150-200bps below current levels.

He reasons that a significant portion of the inflation data, particularly shelter, which accounts for approximately one-third of the CPI, is backward-looking. Therefore, he repeatedly advocated for 50 basis point cuts at the latest FOMC meetings and still proposes one for December.

John Williams of the New York Fed made a complementary comment in Frankfurt. In his remarks, he directly addressed the bond market and bluntly suggested that the market “has got it wrong,” and that the neutral rate that the market estimates is too high. While he didn’t comment on what he’d propose for the FOMC meeting in December, his statement that the neutral rate might be around 1% indicates he’ll support another rate cut.

Contrary to Miran and Williams, Beth Hammack (Fed Cleveland) told attendees of an event in New York that she remains more concerned about inflation than the job market:

The Cleveland Fed chief said she estimates inflation won’t reach the Fed’s 2% target until a year or two after 2026, similar to the median estimate of the Fed’s 19 policymakers. That would mean the Fed will miss its price target for “the better part of a decade,” and risks embedding high inflation in the economy, Hammack said.

It appears that there’s a deep divide within the Fed regarding the December decision. Just like the market, the Fed was also flying blind during the government shutdown when no government data had been released.

As far as I can see, however, the repeated discussion of the “neutral rate” may provide some indication of future monetary policy. Still, it isn't very worthwhile in practice. The rate is purely speculative, and despite complex financial modeling, it is nothing more than a wild guess. I’d go so far as to stress that the Fed cannot make a more precise estimate than the free-market price discovery.

And as Williams said, the market assumes that the neutral rate is much higher than he or Miran thinks. In the end, no one will find out until it’s too late, and the Fed will have to react in one way or another.

What underscores this is a blog comment by San Francisco Fed Chair Mary Daly, in which she discussed recent trends in inflation and the labor market, and what they might indicate for future monetary policy.

She argues that the labor market is softening due to a cyclical decline in labor demand, rather than a secular supply shock resulting from lower immigration. In her view, monetary policy remains restrictive and puts downward pressure on inflation, despite tariffs being reflected in goods prices. However, she raises an important question: whether we are in the 1970s or the 1990s.

In the 1970s, the Fed made a policy mistake by easing too much, whereas the Fed in the 1990s remained more balanced and, according to Daly, paved the way for the roaring 90s. The 90s analogy stems from the advent of computers and the discussion at the time on whether they led to productivity gains. Therefore, she proposes a data-dependent approach to inform future rate cut decisions.

What she leaves out, however, is that Alan Greenspan, chair of the Federal Reserve during the 90s, was making policy decisions on assumptions that turned out to be wrong, as Dario Perkins from TS Lombard nicely summed up:

Early on, Greenspan argued that productivity was under-reported (it was) and deflationary. It was “traumatizing” workers. That part turned out to be wrong. Towards the end he argued that it has raised the equilibrium interest rate. And when he acted on that the bubble burst.

The main point I’d make is that it doesn’t matter if you look at the 90s, the 70s, or today. What seems reasonable for the Fed to do in the moment will likely turn out to be either wrong or dead wrong. And it shouldn’t be surprising to anyone, because the central planning agency of monetary policy, the central banks, might collect thousands of data points. However, despite the vast amount of data being readily available these days, it doesn’t necessarily lead to the correct conclusions.

In fact, it’s simply a central agency looking at current market prices where no one can really understand whether they are above, below, or at the equilibrium price. Traders, producers, and buyers are acting on that basis by selling, producing, or standing aside.

But after all, it’s all just their subjective judgment, not an objective one. They’re already guessing, but have to make up for their mistaken actions, while central banks face no real consequences. However, in the moment, and because the future remains hard to predict because it’s the result of billions of interactions among market participants, it remains a guessing game. And without official government data as a guide, they’re both even more “Blind“ to what might actually happen.

A place inside my brain, another kind of pain

You don’t know the chances,

I’m so blind, blind

BlindKoRn – Blind

Have a great weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for taking the time to read! If you enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to receive each post directly in your inbox. Additionally, I would greatly appreciate it if you could share it on social media or give the post a thumbs-up!

All my posts and opinions are purely personal and do not represent the views of any individuals, institutions, or organizations I may be or have been affiliated with, whether professionally or personally. THEY DO NOT CONSTITUTE INVESTMENT ADVICE, and my perspective may change over time in response to evolving facts. IT IS STRONGLY RECOMMENDED TO SEEK INDEPENDENT ADVICE AND CONDUCT YOUR OWN RESEARCH BEFORE MAKING INVESTMENT DECISIONS.

The neutral rate debat is fascinating right now. Williams and Miran arguing for rates 150-200bps below current levels while Hammack worries about embeding high inflation shows just how uncertain the Fed is. Your Greenspan comparison is spot on, even the best intentioned data-dependent approach can lead to massive misallocations. Markets operting in the dark without CPI and NFP data really underscores the guessing game element.