Beginning Of The End

History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes, a saying attributed to Mark Twain. Whether he said it, it is unknown.

According to the website Quoteinvestigator, a site run by US computer scientist Garson O’Toole, a similar statement by Mark Twain can be found in the Book The Gilded Age: A Tale of To-Day that Twain and his friend, Charles Dudley Warner, wrote together. In a preface to the edition from 1874, it says

History never repeats itself, but the Kaleidoscopic combinations of the pictured present often seem to be constructed out of the broken fragments of antique legends.

I think the quote above is even better than the short version usually attributed to Mark Twain, which he obviously never said or wrote. Looking at actual political and economic developments, one feels reminded of various past events.

Sadly, the actual environment leads me to conclude that the economic outlook for the coming years, especially in the west, is sobering. Although the situation can (obviously) change at any time, current policy in Europe and the United States leads to the conclusion that the triumph for economic and personal liberty after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 was premature.

Instead, it seems that the dominant economic system, capitalism corporatism, is on its way to becoming a centrally planned economic one. Simultaneously, the golden age of globalization and international trade seems to end. On the one hand, the pandemic showed the vulnerability of supply chains, and on the other hand, because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the growing conflict between the west and Russia (and China?).

Before discussing certain parallels between actual and past events, I want to look back at the recent past to investigate how the western economic and financial system got into a situation where government and central bank interventions are recurring in ever shorter intervals.

Ongoing economic integration in the past 40 years led to the offshoring of production of goods from the West to Asia, while western economies transitioned into a service sector economy. Those events led to a deflationary effect in Europe and the United States.

In the 1990s, several countries in the southeast of Asia benefited from extraordinarily high growth rates while western economies grew only slightly. The liberalization of the Asian financial markets made it easier for capital to flow into these countries, Thailand, South Korea, Indonesia, and the Philipines, to name a few. Strong economic growth attracted investors, and the strong inflow of capital fueled the boom further.

Finally, it revealed that the boom was based on weak fundamentals. In those days, most Asian currencies were pegged to the dollar by the Asian central banks. At the beginning of the 1990s, the dollar was weakening rather than strengthening against those currencies, which encouraged Asian businesses and private market participants to take advantage of the situation.

Interest rates for Japanese Yen and US dollars were significantly lower than for the local currencies. Most of them were pegged to the dollar, encouraging Asian banks to borrow dollars and lend domestic currency to businesses.

As the exchange rate remained more or less constant, one could achieve a cost advantage by doing that. Additionally, banks borrowed dollars short-term and lent domestic currency long-term, a classical banking business known as maturity transformation.

However, the accumulation of debt in Asian countries led to a misallocation of capital and fueled a bubble in Asian real estate and equity markets. Cheap money from abroad kept the party going as long as it was assured that there was a constant capital inflow. Poorly developed financial markets in Asia should reveal another problem: banks hardly hedged their currency risk and did not assess the debtors' credit risk very well.

The problem started with the appreciation of the US dollar in 1995 as the burden measured in domestic currency increased for debtors. Simultaneously, Asian central banks did not have enough currency reserves to defend their currencies against the fall in the exchange rate. The rising dollar resulted in more and more borrowers being unable to repay their debt. In the end, the International Monetary Fund had to come to the rescue to prevent the Asian financial system from collapsing.

Scottish analyst Russel Napier calls this moment the birth of the age of debt. The answer of Asian central banks to the crisis and the IMF overtake was that they started accumulating massive foreign exchange reserves. During 1998 and 2019, foreign exchange reserves rose from 203 to 1,256 dollars in Japan, 89 to 441 billion dollars in Hong Kong, 28 to 215 billion dollars in Thailand, and 64 to 345 billion US dollars in Taiwan.

Rising demand for western foreign exchange reserves had a deflationary effect in those countries (falling yields) that western central banks tried to combat with an expansive monetary policy. The rise in liquidity fueled the rise of asset prices, and rising asset prices fueled the increase of debt.

As the central banks artificially lowered the interest rate below the rate the free market would have set, it led to capital misallocation. In our current global monetary system, money is abundant and comes into existence through credit creation. However, natural resources are not. If low rates make investing in the real economy less attractive, money flows into financial assets. Rising asset prices mean that the market participants who own such assets can borrow more and more, which they secure with these. That leads to inequality and economic imbalances, which, at some point, need to readjust to a more sustainable equilibrium.

While it was a mistake to assume that Asia could grow indefinitely and capital inflows never stopped in the 1990s, it was a mistake to think that house prices would not fall nationwide in the US, which led to the Great Financial Crisis in 2008. Another parallelity is that, in both cases, it was a false risk assessment. As the banks bundled mortgages into mortgage-backed securities, AAA-rated, other market participants considered them safe and used them as collateral for other financial transactions. Because of that, the problems in the US housing market became a threat to the international financial system.

As the crisis fully hit markets in 2008, central banks had no other solution than to lower rates again. However, now they did not only lower short-term interest rates. They also started to intervene in long-term interest rates, following the Bank of Japan, which had already started this policy in the early 2000s.

However, the (Keynesian) assumption that lower rates would spur investment and lead to higher growth rates was wrong. The only effect of those policies was that asset prices continued their bull market, and liquidity continued to flow primarily into asset markets. Because of that, consumer price inflation remained low, causing central banks to buy even more long-term bonds because they thought they needed to do more to spur growth and inflation.

Another effect was that businesses started to borrow cheaply to buy back their stock, which fueled their stock prices. Instead of lending money for real economic investment, new liquidity remained within financial markets, and as a result, consumer price inflation remained below 2 %.

It can be argued that central banks failed to fuel real economic activity but succeeded in financial markets as they helped keep the bull market alive. While it was a mistake during the Asian boom to believe that the currency peg would last forever, central bank policy after 2008 encouraged risky behavior because market participants speculated that in case of another crisis, central banks would come to the rescue.

Nevertheless, the situation changed last year. After the pandemic hit and caused a meltdown in financial markets, central banks flooded markets with unprecedented liquidity. Simultaneously, governments ramped up fiscal spending to dampen the effects for businesses that suffered from the implemented policies to fight the virus. International trade came to a halt and the supply of goods contracted while lockdown policies led to a fall in the supply in the service sector.

Additionally, governments started to hand out credit guarantees for loans to businesses that suffered from liquidity problems because of the policies to slow the spread. By doing that, it enabled governments to ensure that companies remained liquid and could influence the supply of money now.

But let me return to Mark Twain’s quote, which says it looks like fragments of the past assemble the present…

In 1923 French troops started to occupy the German Ruhr area because the young Weimar republic did not fulfill their obligations from the Treaty of Versailles. The Ruhr area was Germany’s leading source for its primary source of energy, coal. After the occupation, the German chancellor Wilhelm Cuno called for passive resistance.

Numerous miners stopped working, and as a result, production fell, and prices sharply increased. The German government stepped in and started to pay the workers wages. How did it do that? By issuing new units of currency, which further fueled price increases. The end of the passive resistance also marked the end of the Weimar hyperinflation and resulted in German currency reform.

As Russia invaded Ukraine, Europe, with Germany primarily dependent on Russian gas, announced that it plans to end Russian gas imports at some point in the future. By that point, Russia had already started to lower gas flows to Europe, which caused a rise in Energy prices. Meanwhile, Russia stopped gas flows through Nordstream I completely, and although gas prices have fallen since then, they are still about tenfold higher than the average price of 2015 - 2020. Now that the Nordstream pipelines are damaged, it is unclear if gas flows could ever return if it comes to an agreement, which is currently highly unlikely.

European states try to dampen the effects of rising energy prices with another increase in government spending instead of increasing supply (Europe has several gas sources below its surface). To do this, they issue new debt that many banks buy. Banks can use their abundant bank reserves to do that, another result of the ECB’s Quantitative Easing programs. However, government spending flows into the real economy and might lead to further consumer price increases.

One might say, like Germany in 1923, European nations (including the United Kingdom) now try to fight an energy crisis by issuing new currency units. As it did back then, that will impact foreign exchange rates. Being net importers of energy, the UK and Europe need to print domestic currency to buy dollars to buy energy from net exporters of energy (USA). That causes a euro devaluation, leading to higher energy import prices.

Due to the current energy crisis, the euro and the pound trade more like emerging market currencies. That results in similar implications for the UK and Europe as for Southeast Asia during the Asian financial crisis.

To stop the fall in the exchange rate, the ECB and the Bank of England would have to sell currency reserves to buy domestic currency. But even if the Euro Area sells all of its foreign exchange reserves, it can only finance imports for two months. Japan and other Asian countries have a much larger buffer because, as previously noted, they have accumulated much more foreign exchange reserves after the Asian Financial Crisis. Theoretically, Japan could finance imports for 16 months with its foreign exchange reserves.

Recently, the Bank of Japan verbally intervened in currency markets to support the Yen. However, by only announcing that it might use its foreign exchange reserves to defend the Yen, it did not have a lasting effect. USD/JPY sharply fell after the announcement but quickly returned to the level before the BoJ intervened.

As noted in the previous piece of the Weekly Wintersberger, the United Kingdom has already pivoted and stopped its QT plans. It is now temporarily buying long-term GILTs to guarantee financial stability. However, recently, the Bank rejected all offers to buy, which caused a bear steepening of the yield curve. This week, another central bank surprised markets: the Royal Bank of Australia hiked rates by only 25 basis points, less than expected.

It seems as if the phantasy of continuous aggressive rate hikes is already starting to evaporate. In Europe, central bank officials still talk about rising rates, but there are still no plans for QT, and I suspect there will never be any QT in the Eurozone.

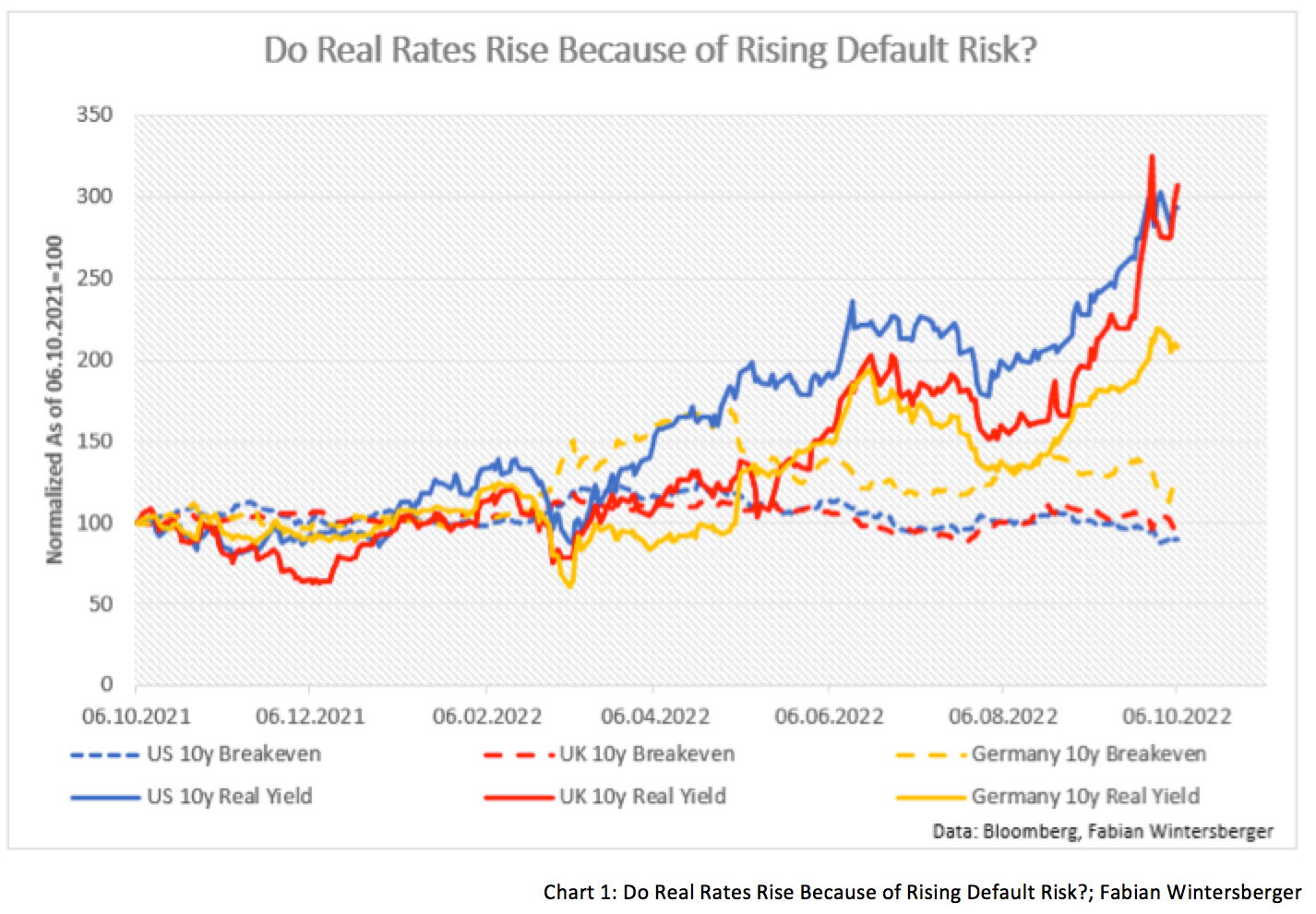

Usually, one would expect inflation expectations to increase in a high-inflation environment if the government is ramping up fiscal spending. However, breakeven rates remain stable, but real rates continue to rise. Do market participants start to price in a higher probability of default?

I want to add that the probability of default, measured by Credit Default Swaps, is still very low in all those countries, as government bonds are still considered risk-free. But to add another fragment of legend, back in 2007, mortgage-backed securities were also regarded as risk-free.

One might argue that, as history tells, governments hardly ever become insolvent because central banks ever can print any amount of currency required to keep it liquid. That is definitely true, and I also expect this to happen this time. However, this is also my argument for why inflation expectations might be in for a drastic repricing.

This week, many analysts and commentators in the financial media started to speculate about a potential Fed pivot again. I re-read the transcript of Jerome Powell’s FOMC press conference. August job openings marked their most significant downturn since the pandemic. However, I still think that that does not support the case for a pivot because there are still 1.7 unemployed people for one job opening. I think the Fed will pivot at some point because some systemic risk pops up, just like in the UK.

People should listen to Jerome Powell’s words. According to him, the Fed will stop hiking when all rates across the yield curve exceed the inflation rate. When that is accomplished has to be seen because it depends on the future course of inflation.

According to several studies, central bank policy has a lagging effect of 1 - 2 years. Probably inflation has already peaked (several good arguments support this), but no one knows for sure. Looking at US M2 money growth still does not support the case for disinflation.

I have always argued QE might be in for a comeback sooner than most people think, but given the current situation, it is probable that the Fed will not pivot this year. My thesis is that the Fed will be forced to pivot because of a similar event as in the UK. Nevertheless, one should be aware that the market move could be much more severe because foreigners alone held 7.5 trillion dollars in treasuries.

If the Fed slams the breaks and socializes risk, equity markets should benefit, at least in the short term. Then, we might see an enormous bear market rally. Still, this will lead to well-known problems of capital misallocation. Further, since the government is already directly influencing the money supply through credit guarantees, one could conclude that the state will intervene in more and more sectors of the economy.

As we all know, the road to hell is paved with good intentions. We will see when the Fed finally throws the towel again and starts intervening in the treasury market by restarting QE. Finally, I have no doubts that central banks will inflate the debt away in the end, and that, at some point in the future, the state will force institutional investors to buy government bonds at a yield below inflation. If that occurs, the top of the bear market rally is reached.

My thesis is that the age of debt is ending, and an age of financial repression will follow. However, as this will happen sooner in Europe and elsewhere than in the United States, capital will continue to flow into the US, propping up the dollar. At some point, governments will be forced to induce capital controls to hinder outflows and end the free movement of capital. There are many examples in history where that happened…

I borrowed the title for today’s commentary from the US band Spineshank because I think that the first line of the chorus is perfectly describing the situation we will finally face:

It’s the beginning of the end, and I don’t know where we lost control

I wish you a splendid weekend!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for reading! You can subscribe and get every post directly into your inbox if you like what I write. Also, it would be fantastic if you shared it on social media or liked the post!

(All posts are my personal opinion only and do not represent those of people, institutions, or organizations that the owner may or may not be associated with in a professional or personal capacity.)

Quite a dark piece with some distrurbing conclusions, definitely a lot to ponder. Enjoyed it, thanks

A great read ... concise and clarifying descriptions of previous capital market misallocations** that parallel our current mess.

** Weimar, Asian Contagion, GFC and QE+++...