Note: The opinion piece was written before the Trump/Zelensky incident.

Europe was created by history. America was created by philosophy – Margaret Thatcher

1. Intro: How Many Times Must I Beat My Head Against A Wall

If we’re being completely honest about it, there’s no denying that the current political, economic, and financial landscape in Europe has been sliding into a slow but persistent state of decline.

The glory days of Western European countries as economic giants are long behind us. These economies now face a steady downturn, bogged down by self-inflicted political troubles and a repeated dependence on economic policies that fail to deliver the results everyone keeps hoping for.

The EU and its major members' influence on the big geopolitical stage is trending toward insignificance. Without the UK and its special relationship with the United States, the EU has lost a significant chunk of its geopolitical clout. However, to be fair, the UK hasn’t gained much importance since leaving either.

So far, Europe’s decade has felt like a drawn-out sequel to the 2010s. Europe’s geopolitical track record then amounted to little more than parroting US administrations. Economically, it never bounced back from the hammer blow of the 2008 Great Financial Crisis and the European government debt crisis that followed.

While the geopolitical struggles look poised to drag on for a while, the EU is at least trying to tackle its self-inflicted economic challenges. But here’s the twist of historical irony: the man tapped to find solutions and get European economies back on track is none other than Mario Draghi—the same person whose monetary policies during the 2010s achieved pretty much nothing in overcoming those earlier challenges.

In this piece, I want to take a closer look at the geopolitical, economic, and monetary policy challenges that Europe, the Eurozone, and the ECB have been wrestling with, what they’ve tried to do about it, and then offer some thoughts on what the future might hold. Sure, the diagnosis might look pretty hopeless at first glance—but the main lesson from history is that, in many cases, things turn out better than anyone initially expected. Maybe there’s more than just a bearish case for Europe. With some luck and the right policies, this so-called European demise might be another gloomy prediction that never entirely comes true.

2. Foundations That Could Never Break

2.1 Triumph Over Tragedy

One obvious challenge has always been Europe’s position in the geopolitical landscape, which became especially clear in the 1990s during German reunification. Europeans felt pretty comfortable in their role as partners with the United States. Granted, they were never equals—Germany and France had their opinions heard by US administrations, but it wasn’t exactly a balanced partnership.

In most cases, the endgame was whatever the US wanted anyway. Consider the breakup of the former Yugoslavia: when it finally happened, the interests of the NATO alliance more or less lined up, though the motivations weren’t identical. Europeans saw it as “a way to establish the EC’s [European Community’s] importance in the new global system.” At the same time, the Americans viewed it as a handy justification to keep their troops stationed in Europe, even going so far as to sabotage a series of peace offers between 1992 and 1995.

Still, this didn’t do much lasting damage to the US-Europe relationship. A few years later, both sides were back on the same page during the NATO intervention in Kosovo (1999). Germany, France, and Great Britain consistently supported the US throughout that period. After the 9/11 attacks, the world rallied behind the United States in the fight against Islamic terrorism, and Europe was no exception.

Long story short, things shifted in 2003 when Germany and France refused to support the Iraq invasion. That’s when Europe’s geopolitical importance started to slip noticeably. To regain some of that lost influence, its leaders fell back into line with the US during interventions in Libya and Syria.

Meanwhile, behind all of this, Europeans were deeply invested in NATO’s eastward expansion alongside the US. After all, there was no separate European defense alliance to speak of, and the enlargement of the European Union to the east followed in NATO’s footsteps. It was probably seen as a helpful tool at the time. So, the idea of creating their own independent security structure? That never really crossed Europe’s mind.

2.2 The Sights And Sounds, The Rise And The Fall

Then, Ukraine happened, although one must acknowledge that the build-up to that war also traces back to the early 1990s and the final fall of the Soviet Union. Europe’s initiative since 2022 can be summed up as “mirroring Biden.” That was no wonder for Eastern European countries, who—arguably due to various experiences—considered Russia a threat. However, it was a change for Germany, which had always tried to normalize Russian relations during the Merkel years.

What followed was a barrage of sanctions—sanctions, sanctions, and more sanctions. So far, the EU has rolled out 16 packages against Russia. There’s debate about how hard they’ve actually hit Russia’s economy, but one thing’s sure: they haven’t hit hard enough to stop the war. Now, with the Trump administration changing course—suddenly seeming to recognize that Russia is a power with regional interests worth hearing—the EU finds itself isolated, like a captain of a ship whose wheel isn’t attached to anything.

2.3 Can’t Rewrite History, Yesterday Is Gone

Where Europe goes from here on the geopolitical landscape remains to be seen. Its irrelevance is painfully apparent. While it’s tough to predict how far the US might actually pull back from Europe, the current crisis also presents a chance—a chance to finally stand on its own two feet defensively and rebuild a geopolitical reputation as an actor with its own unique stance.

What Europe didn’t do after the fall of the Soviet Union, it needs to do now: move forward and create its own security structure. Under the current European leadership, though, the signals point to ramping up military spending and maintaining a hard stance against Russia due to “moral issues.” Whether that’s the most intelligent economic move is up for debate, but Europe’s economy could certainly benefit from the vast amounts of commodities flowing from the East.

As the Trump administration looks to normalize relations with Russia and advance peace talks, Europe remains stuck in the Biden-era mindset. Whether European leadership will commit to normalizing relations with its neighbor Russia under some kind of common security order and restoring diplomatic ties is anyone’s guess. So far, it doesn’t seem likely, but having more options on the table would definitely help, especially with the pressing need for lower energy prices.

These geopolitical events have driven up European energy prices and hampered production ever since, so let’s shift gears and look at Europe’s economic situation.

3. Was Moving Forward A Mistake?

Beyond the geopolitical challenges, Europe is also staring down an enormous economic challenge moving forward—one that mirrors its geopolitical troubles in being predominantly self-made. With the United States effectively guaranteeing Europe’s security, Europe enjoyed the luxury of pouring government money into expanding the welfare state. During times of strong economic growth and solid production, that approach seemed sustainable enough. But over time, the priorities shifted from creating wealth to distributing it.

The debate over this has heated up since the apparent fallout from the Russia-Ukraine situation and the resulting spike in energy prices. Still, truth be told, the European growth model lost its way well before that, right after the Great Financial Crisis. In the early 2000s, Eurozone economies were growing more or less in line with the US, but the 2010s changed all that.

The ECB cut interest rates to zero to support government finances and boost economic growth, but the economy still stagnated. Several EU spending packages meant to revive things also didn’t make much of a dent. Keynesianism turned out to be a significant failure for Europe. It never unleashed the potential of a free economy, which was held back by massive overregulation and heavy-handed central planning.

3.1 Yesterday Is Gone

And yet, the era of “too low inflation” and zero percent interest rates has ended for now, while low growth stubbornly hangs on. Despite Christine Lagarde’s almost Yoda-like comment during the latest ECB press conference (“Recovery there is. Stagflation there is not”), Europe still faces the very real danger of continuous stagnation.

Nevertheless, there’s at least a glimmer of hope in the fact that Ursula von der Leyen has acknowledged that something needs to be done to get the economy back on track. Her pick to deliver the necessary insights is Mario Draghi, who’s already published a report with several recommendations.

Draghi points out some critical issues: Europe is losing competitiveness due to extreme regulation and suffering from being a net energy importer. The economically obvious solution—bringing Russian energy back into the mix—is sidelined for “moral” reasons.

Instead, he aligns with von der Leyen, pushing to double down on the green transition as a way to “boost growth.” But if you look at Germany, a country that went all-in on that transition, energy prices are among Europe's highest.

4. Or Is That Me Pretending?

The situation looks dire if you examine consumption and production closely. Eurozone industrial production has fallen below 2015, but the drop isn’t as steep as consumer weakness suggests—exports are still helping.

Looking ahead, the threat of Trump imposing tariffs on European products could put Europe in an even tougher spot. The US has already become Europe’s biggest export market, and tariffs and policies encouraging companies to produce goods directly in the US would translate into severe economic pressure.

Furthermore, several months have passed since Draghi released his report, and so far, nothing substantial has happened beyond a few loud statements. Draghi himself seems a bit annoyed about the lack of action.

On February 14, he published a commentary in the Financial Times, where he spelled out that Europe doesn’t just need to worry about US tariffs. Beyond that, Europe has put up its own trade barriers between member states to protect domestic producers. According to the IMF, he writes, these barriers are equivalent to 45% tariffs on manufacturing and 110% for services.

Then there’s the excessive regulation piling on top of that, stifling growth in innovative digital services and dragging down productivity gains, which cuts into profits for small European tech firms. Draghi argues that while globalism has brought down external trade barriers, internal trade barriers within the EU have only worsened.

And yet, despite pointing out some of the most profound economic problems, Draghi once again skips over the obvious solution: freeing up capital by lowering taxes, slashing regulations and internal trade barriers, and letting the free market do its job. Why he avoids this, one can only guess—probably because it runs too counter to his Keynesian instincts.

Instead, his proposal sticks to a predictably Keynesian script: centralization, focusing on multilateral economic goals, and “a more proactive use of fiscal policy – in the form of higher productive investment – would help lower trade surpluses and send a strong signal to firms to invest more in R&D.” (emphasis added).

What could possibly go wrong when the government picks winners and losers with taxpayer money? If you look at all the malinvestment, the EU has already racked up quite a lot over the years. What Draghi calls a “signal” for more R&D investment essentially boils down to businesses lining up for government handouts.

Still, you have to give him some credit—he’s at least thinking about potential solutions and trying to improve things. But his solutions echo more of the same, an approach that’s failed repeatedly. Plus, it’s safe to assume that his talk of reducing regulation will stay a shallow promise under the current EU leadership. And the idea of creating growth by doubling down on green policies? That’s unlikely to deliver either growth or cheap energy, resting as it does on overly optimistic assumptions about energy storage capacity.

4.1. The Beat Goes On

Beyond that, unleashing more government investment—or, put more bluntly, piling on more debt financing—that doesn’t produce real growth will only end up as an inflationary boost. With the ECB still in the late stages of wrestling down an inflation crisis, it’d be risking another wave of price spikes anyway.

So, we need to think about the ECB’s role here. The ECB has started engaging on multiple fronts within the current tangle of economic, geopolitical, and political struggles. The times when the European Central Bank was just an institution focused solely on managing the currency area’s monetary policy are long gone.

Recently, the ECB, in the person of Christine Lagarde, has met with personnel from the EU Commission and other politicians on multiple occasions. That flies entirely in the face of the ideal of an institution free from political influence. I suppose, though, that everyone’s always looking to grab a little more of it within the sphere of power.

Even if you just focus on its monetary policy mandate, the ECB would have plenty on its plate. If you’re a frequent reader of my stuff, you know I’ve criticized their past actions more than once, so I’ll keep this short. After the ECB flooded the market with liquidity in 2020, it totally misjudged the situation, brushing off the rise in inflation as a temporary bump. Then it tried to talk inflation down, which didn’t work and ended up raising interest rates too late, right as Russia invaded Ukraine and energy prices shot through the roof.

Since then, inflation has normalized and keeps trending lower, though the ride’s been anything but smooth. If you look at the current Eurozone CPI, it seems interest rates are only mildly restrictive, with a real rate of 0.4%.

From a Keynesian perspective, the caution of ECB governing council member Isabel Schnabel about the restrictiveness of interest rates makes some sense. Neo-Keynesians rely on inflation models that don’t bother with the money supply. Instead, they build “heat maps” where they categorize certain goods and services, or groups of them, to figure out where there’s “inflation pressure” in the economy.

From an Austrian perspective, though, price changes are more of a symptom than the root cause of inflation, which is really about expanding the money supply. As I’ve noted in other pieces, short-term price movements are heavily influenced by supply and demand shifts, the market's finding of new balance points, and the expectations of economic actors.

The latest yearly growth rate of the M3 money supply in the Eurozone is sitting at 3.5%. Monetarists would say that’s too high for an inflation rate of around 2%. Unlike in the US, velocity hasn’t picked up in the Eurozone, meaning money demand is still high and doesn’t feed into accelerating inflation.

If you smooth out the monthly ups and downs and use longer-term metrics like the 3- or 6-month average, real interest rates look a bit more restrictive, though they’re down from their recent highs. Looking back, they’re still higher than ever since the Eurozone sovereign debt crisis. If inflation doesn’t stick around or pick up again—as some bond vigilantes warn—then any weakness spilling over from the US could drag Eurozone inflation down with it, making real yields feel even more restrictive.

Growth in the Eurozone is still sluggish. In the short term, I think only an unexpected inflation drop could slightly brighten consumer confidence. If the US economy cools off and cuts rates, too, that could help bring down Eurozone government bond yields. The yield curve is currently bull-steepening, with short-term rates dropping faster than long-term ones.

The long end of the yield curve is still a little jittery about inflation hanging around, and that’s acting as a tailwind for duration. Bond investors are getting a bit nervous, especially with the current chatter about scrapping Germany’s debt brake and ramping up defense spending.

Suppose the ECB decides to pause rate cuts at one of the next meetings. In that case, I see two possible scenarios: either an initial drop in bonds that get bought up as higher rates for longer start to weigh on growth or an immediate rise driven by concerns over economic growth. If the ECB’s right and inflation isn’t beaten yet—say, ongoing imbalances keep it elevated—then bunds could drop back again. For short-term rates, the downside seems pretty limited. Personally, I lean toward thinking the ECB is misreading the situation once more, digging through relative price changes to spot “inflation pressure” like it’s some kind of needle in a haystack.

And yet, the euro has gained some ground against the dollar, pushing toward the 1.05 mark again, which should help ease inflationary pressures from the commodity sector. That’s also reflected in the S&P Global Flash PMI for Germany, where input and output price inflation has ticked down.

Plus, as Kamil Kovar from Moody’s Analytics pointed out, “the latest upside surprise in inflation was driven by large one-offs than by broad based acceleration, with center of the distribution actually moving lower.” With all that data in mind, another short-term inflation run-up seems unlikely unless there’s a significant supply shock that craters output.

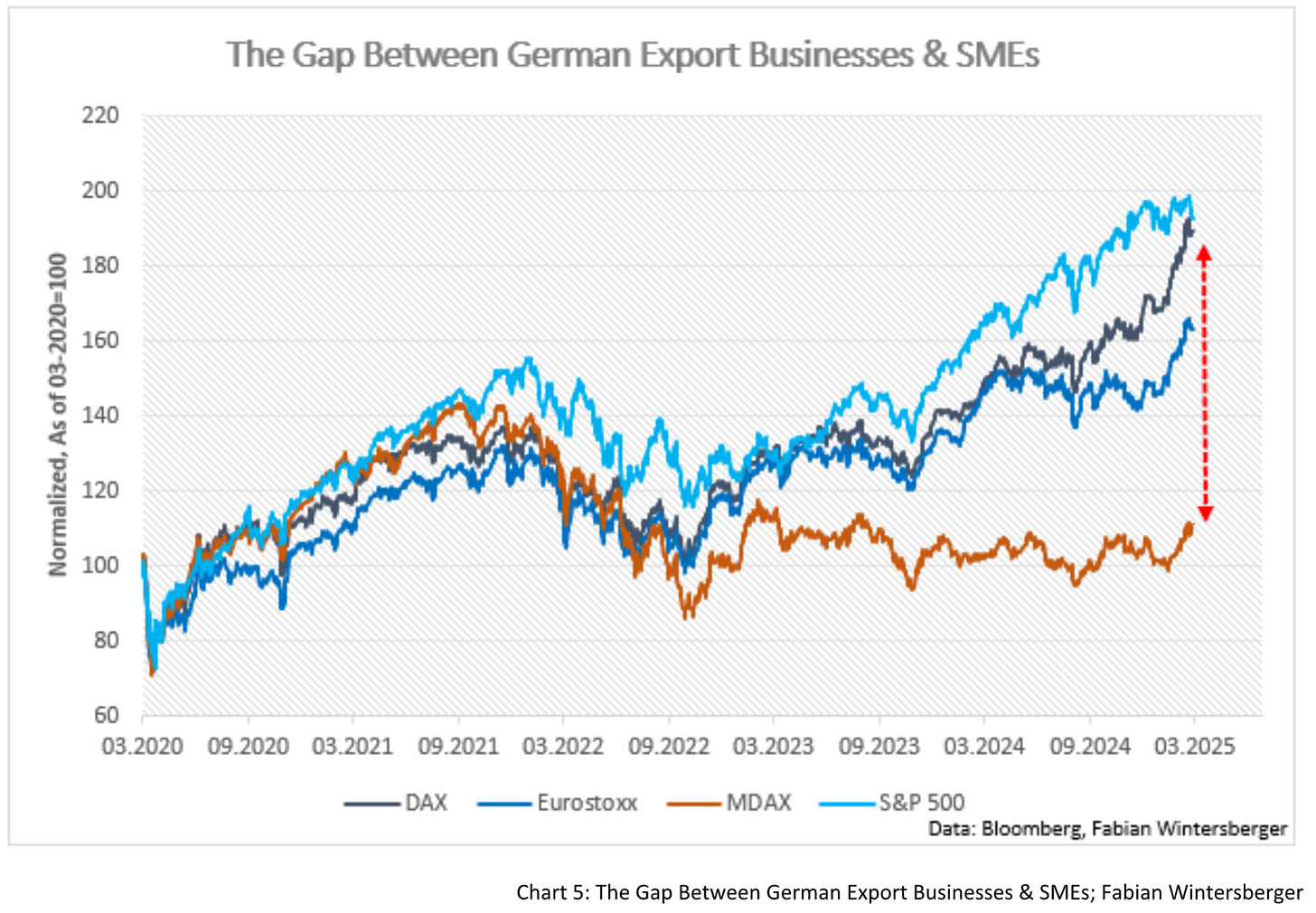

Still, as represented by the DAX, German big business doesn’t seem fazed by the domestic economic gloom. Since January, the DAX has been outperforming the US S&P 500 and has now grown almost as much as it has since the post-Covid crash in March 2020. But when you stack that up against medium-sized companies, the gap becomes stark, underscoring just how weak domestic demand really is.

5. What Happened To My Happy Ending?

So, is the European economy doomed to fail? Sure, all the evidence points to ongoing struggle, but there are at least some glimmers of hope on the horizon. To borrow from Mark Twain, “Reports of [Europe’s] death are greatly exaggerated.” That said, we need to break this down into two different angles.

First off, there are short-term tailwinds that could turn into long-term drags. One of those is a sizable package to ramp up defense spending. It’s just a guess, but it seems likely this would be financed at the European Union level through the issuance of more joint bonds, with European defense companies reaping the benefits.

I’ve got a hunch there’s more to why the EU is pushing this—defense might just be a secondary piece. Think back to what US war hawks argued: the money for Ukraine was about “rebuilding the US industrial base.” It’s very likely those massive spending bills helped juice US growth, and the same could play out in the EU.

But as with everything in economics, there’s no free ride. Money and resources poured into building a stronger defense can’t be spent on projects that directly benefit domestic consumers. So, it’s possible that the growth boost from such a package could wear off over time, and those same old growth concerns would creep back in.

Another glimmer of hope would be if at least some of Mario Draghi’s proposals—like cutting regulation and wiping out internal tariffs—actually get implemented at some point. European businesses could see lower costs and less bureaucracy, which should be a shot in the arm for growth. But here’s the catch: it seems unlikely to lead to an overall reduction in bureaucracy within the EU. I’d wager the EU Commission would create more red tape just to figure out “how to reduce bureaucracy.”

That means a chunk of the money spent would probably feed Brussels’ bureaucratic machine rather than flow into productive economic sectors. The Draghi report could easily become one of those projects where the bad ideas are implemented while the good stuff is left on the shelf.

On top of that, it’d be a big help if those changes came alongside a combination of fortunate events. Let’s say interest rates are restrictive—an event that brings them down, paired with something that lifts domestic economic confidence, could really fuel a recovery. Picture inflation trending lower over the course of the year, geopolitical tensions calming down, and all that coinciding with less regulation and more investment. That’d be a welcome boost to spark a turnaround.

Another key factor would be lower energy prices—there are a few ways that could happen. Investing more in building nuclear power plants could indeed help bring energy costs down eventually. However, it will take a longer time to come online because construction doesn’t happen overnight.

Even though Europeans are still playing hardball on the geopolitical front, a long-lasting solution and peace in Ukraine would be a massive win for the economy. The European leadership might see it differently, but if you’re serious about chasing a nuclear energy strategy, you need a transition plan in the meantime—and that could mean natural gas from the cheapest supplier around. Relying solely on US LNG isn’t enough; more options are needed, which is where restoring some kind of diplomatic relationship with Russia could be helpful. Of course, you could argue against that step on “moral” grounds, but morality shouldn’t be the deciding factor in geopolitics. If peace in Ukraine gets locked in, that option should absolutely be on the table.

And here’s where the pessimism creeps back in. European leaders have never been great at admitting when their chosen path isn’t working. Usually, they just double down and call for even higher government spending. However, leaning on government investments doesn’t automatically lead to economic growth. For example, look at Europe’s track record in the 2010s for proof of that.

Foundations that will never break,

Was moving forward a mistake?

Or is that me pretending?

What happened to my happy ending?The Ghost Inside - Aftermath

Have a great month!

Fabian Wintersberger

Thank you for taking the time to read! If you enjoy my writing, you can subscribe to receive each post directly in your inbox. Additionally, I would greatly appreciate it if you shared it on social media or gave the post a thumbs-up!

All my posts and opinions are purely personal and do not represent the views of any individuals, institutions, or organizations I may be or have been affiliated with, whether professionally or personally. They do not constitute investment advice, and my perspective may change over time in response to evolving facts. IT IS STRONGLY RECOMMENDED TO SEEK INDEPENDENT ADVICE AND CONDUCT YOUR OWN RESEARCH BEFORE MAKING INVESTMENT DECISIONS.